BMW K75

FOUR MINUS ONE EQUALS K75

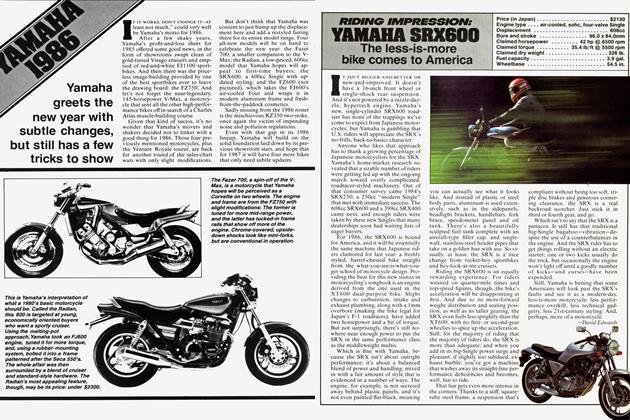

BMW’S CONCEPT FOR ITS NEW K75 is nothing if not audacious: Take a successful four-cylinder motorcycle, chop one cylinder from its engine, and then stuff the resulting smallerdisplacement Triple back into the Four’s chassis.

In this way, the new K75 expands the BMW range, but can it be taken seriously? After all, would Yamaha create an FZ560 by lopping one cylinder off of the FZ750 and recycling the 750 frame? Or Honda a VF750R V-Three version of the VF1000R?

Regardless of how other manufacturers might feel, BMW takes this idea seriously indeed. From the very beginning of the K program, BMW planned to produce both the four-cylinder K100 and the three-cylinder K75. Only a marketing decision dictated that the K100 got released first.

And make no mistake: The K75 really is the K100 minus its front cylinder, with only a few additional changes. First is engine tune; instead of the 67.5 bhp that might be expected from three-fourths of a 90horse K100, the K75 produces 75 bhp. This power boost is through straightforward means. The K75’s cam timing is longer, and its compression ratio is up to 11.0:1 from 10.2:1 on the K100. The result is more peak power per cubic centimeter than on the K100, although with correspondingly less mid-range.

Aside from engine tune, the other major difference between the two engines is the addition of a balance shaft to the K75. Because the Three was always a planned addition to the line, provision for this balancer was made in the original design. The shaft that drives the clutch and water pump was designed so it could be transformed into a balance shaft by adding counterweights; the 1 -to-1 speed ratio between crank and shaft was already correct. With the weighted shaft, the K75 is smoother than its four-cylinder parent.

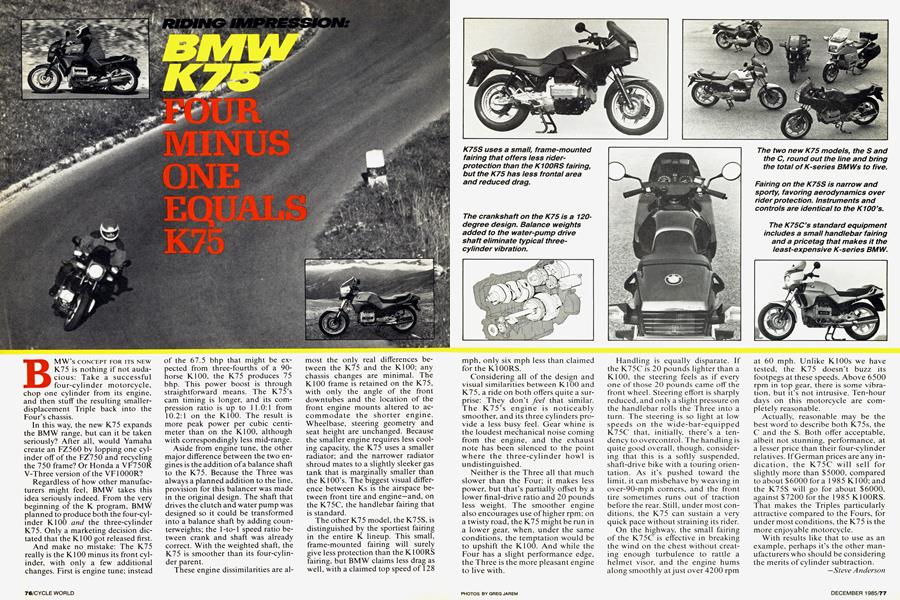

These engine dissimilarities are almost the only real differences between the K75 and the K100; any chassis changes are minimal. The K100 frame is retained on the K75, with only the angle of the front downtubes and the location of the front engine mounts altered to accommodate the shorter engine. Wheelbase, steering geometry and seat height are unchanged. Because the smaller engine requires less cooling capacity, the K75 uses a smaller radiator; and the narrower radiator shroud mates to a slightly sleeker gas tank that is marginally smaller than the K 100’s. The biggest visual difference between Ks is the airspace between front tire and engine—and, on the K75C, the handlebar fairing that is standard.

The other K75 model, the K75S, is distinguished by the sportiest fairing in the entire K lineup. This small, frame-mounted fairing will surely give less protection than the K100RS fairing, but BMW claims less drag as well, with a claimed top speed of 128 mph, only six mph less than claimed for the KIOORS.

Considering all of the design and visual similarities between KlOO and K75, a ride on both offers quite a surprise: They don’t feel that similar. The K75’s engine is noticeably smoother, and its three cylinders provide a less busy feel. Gear whine is the loudest mechanical noise coming from the engine, and the exhaust note has been silenced to the point where the three-cylinder howl is undistinguished.

Neither is the Three all that much slower than the Four; it makes less power, but that’s partially offset by a lower final-drive ratio and 20 pounds less weight. The smoother engine also encourages use of higher rpm; on a twisty road, the K75 might be run in a lower gear, when, under the same conditions, the temptation would be to upshift the KlOO. And while the Four has a slight performance edge, the Three is the more pleasant engine to live with.

Handling is equally disparate. If the K75C is 20 pounds lighter than a KlOO, the steering feels as if every one of those 20 pounds came off the front wheel. Steering effort is sharply reduced, and only a slight pressure on the handlebar rolls the Three into a turn. The steering is so light at low speeds on the wide-bar-equipped K75C that, initially, there’s a tendency to overcontrol. The handling is quite good overall, though, considering that this is a softly suspended, shaft-drive bike with a touring orientation. As it’s pushed toward the limit, it can misbehave by weaving in over-90-mph corners, and the front tire sometimes runs out of traction before the rear. Still, under most conditions, the K75 can sustain a very quick pace without straining its rider.

On the highway, the small fairing of the K75C is effective in breaking the wind on the chest without creating enough turbulence to rattle a helmet visor, and the engine hums along smoothly at just over 4200 rpm at 60 mph. Unlike KlOOs we have tested, the K75 doesn’t buzz its footpegs at these speeds. Above 6500 rpm in top gear, there is some vibration, but it’s not intrusive. Ten-hour days on this motorcycle are completely reasonable.

Actually, reasonable may be the best word to describe both K75s, the C and the S. Both offer acceptable, albeit not stunning, performance, at a lesser price than their four-cylinder relatives. If German prices are any indication, the K75C will sell for slightly more than $5000, compared to about $6000 for a 1985 KlOO; and the K75S will go for about $6000, against $7200 for the 1985 K100RS. That makes the Triples particularly attractive compared to the Fours, for under most conditions, the K75 is the more enjoyable motorcycle.

With results like that to use as an example, perhaps it’s the other manufacturers who should be considering the merits of cylinder subtraction.

—Steve Anderson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

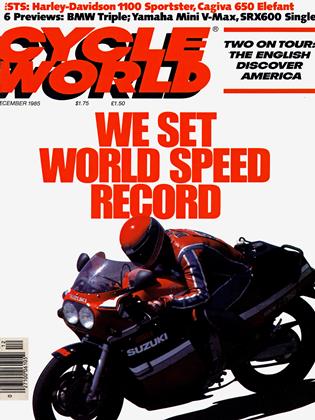

EditorialThe Making of A Record

DECEMBER 1985 By Paul Dean -

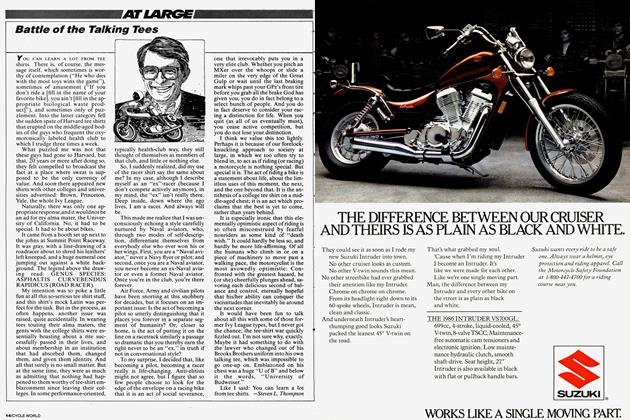

At Large

At LargeBattle of the Talking Tees

DECEMBER 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Walkman Cometh

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

DECEMBER 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

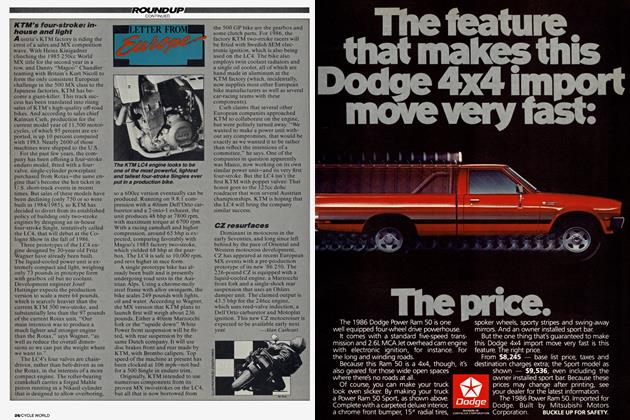

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

DECEMBER 1985 By Alan Cathcart