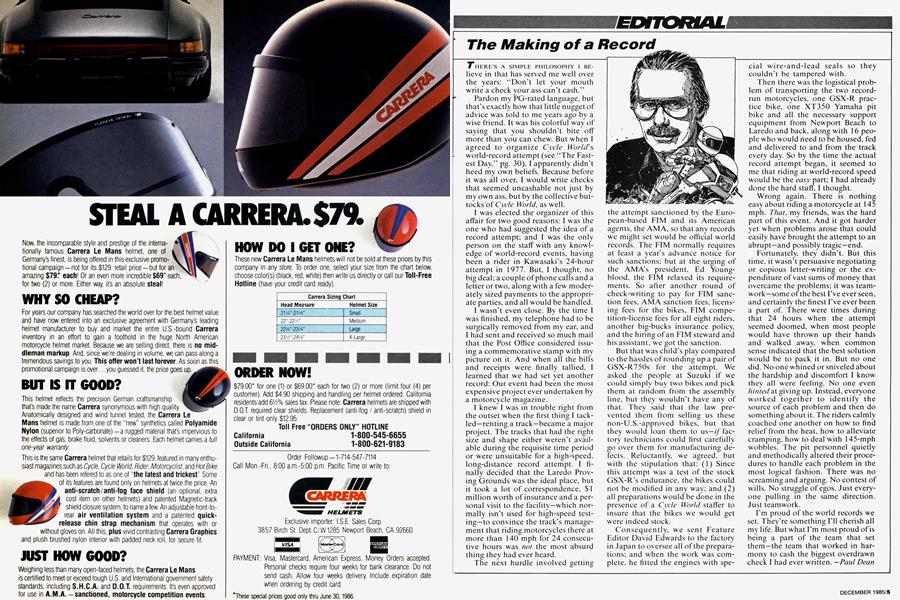

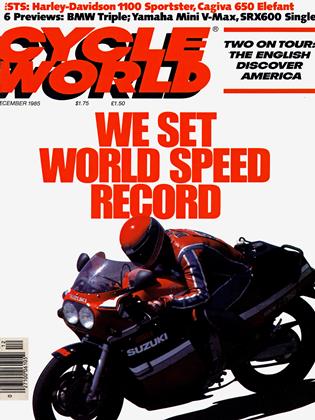

The Making of a Record

EDITORIAL

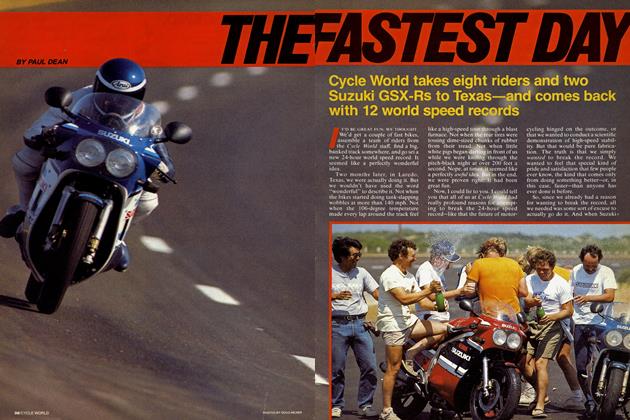

THERE’S A SIMPLE PHILOSOPHY I BElieve in that has served me well over the years: “Don’t let your mouth write a check your ass can’t cash.” Pardon my PG-rated language, but that’s exactly how that little nugget of advice was told to me years ago by a wise friend. It was his colorful way of saying that you shouldn’t bite off more than you can chew. But when I agreed to organize Cycle World's world-record attempt (see “The Fastest Day,” pg. 30), I apparently didn’t heed my own beliefs. Because before it was all over, I would write checks that seemed uncashable not just by my own ass, but by the collective buttocks of Cycle World, as well.

I was elected the organizer of this affair for two good reasons: I was the one who had suggested the idea of a record attempt; and I was the only person on the staff with any knowledge of world-record events, having been a rider in Kawasaki’s 24-hour attempt in 1977. But, I thought, no big deal; a couple of phone calls and a letter or two, along with a few moderately sized payments to the appropriate parties, and all would be handled.

I wasn’t even close. By the time I was finished, my telephone had to be surgically removed from my ear, and I had sent and received so much mail that the Post Office considered issuing a commemorative stamp with my picture on it. And when all the bills and receipts were finally tallied, I learned that we had set yet another record: Our event had been the most expensive project ever undertaken by a motorcycle magazine.

I knew I was in trouble right from the outset when the first thing I tackled—renting a track—became a major project. The tracks that had the right size and shape either weren't available during the requisite time period or were unsuitable for a high-speed, long-distance record attempt. I finally decided that the Laredo Proving Grounds was the ideal place, but it took a lot of correspondence, $ 1 million worth of insurance and a personal visit to the facility—which normally isn’t used for high-speed testing—to convince the track’s management that riding motorcycles there at more than 140 mph for 24 consecutive hours was not the most absurd thing they had ever heard.

The next hurdle involved getting the attempt sanctioned by the European-based FIM and its American agents, the AMA, so that any records we might set would be official world records. The FIM normally requires at least a year’s advance notice for such sanctions; but at the urging of the AMA's president, Ed Youngblood, the FIM relaxed its requirements. So after another round of check-writing to pay for FIM sanction fees, AMA sanction fees, licensing fees for the bikes, FIM competition-license fees for all eight riders, another big-bucks insurance policy, and the hiring of an FIM steward and his assistant, we got the sanction.

But that was child’s play compared to the hassles of rounding up a pair of GSX-R750s for the attempt. We asked the people at Suzuki if we could simply buy two bikes and pick them at random from the assembly line, but they wouldn’t have any of that. They said that the law prevented them from selling us these non-U.S.-approved bikes, but that they would loan them to us—if factory technicians could first carefully go over them for manufacturing defects. Reluctantly, we agreed, but with the stipulation that: (1) Since this attempt was a test of the stock GSX-R’s endurance, the bikes could not be modified in any way; and (2) all preparations would be done in the presence of a Cycle World staffer to insure that the bikes we would get were indeed stock.

Consequently, we sent Feature Editor David Edwards to the factory in Japan to oversee all of the preparations; and when the work was complete, he fitted the engines with special wire-and-lead seals so they couldn’t be tampered with.

Then there was the logistical problem of transporting the two recordrun motorcycles, one GSX-R practice bike, one XT350 Yamaha pit bike and all the necessary support equipment from Newport Beach to Laredo and back, along with 16 people who would need to be housed, fed and delivered to and from the track every day. So by the time the actual record attempt began, it seemed to me that riding at world-record speed would be the easy part; I had already done the hard stuff, I thought.

Wrong again. There is nothing easy about riding a motorcycle at 145 mph. That, my friends, was the hard part of this event. And it got harder yet when problems arose that could easily have brought the attempt to an abrupt—and possibly tragic—end.

Fortunately, they didn’t. But this time, it wasn’t persuasive negotiating or copious letter-writing or the expenditure of vast sums of money that overcame the problems; it was teamwork-some of the best I’ve ever seen, and certainly the finest I’ve ever been a part of. There were times during that 24 hours when the attempt seemed doomed, when most people would have thrown up their hands and walked away, when common sense indicated that the best solution would be to pack it in. But no one did. No one whined or sniveled about the hardship and discomfort I know they all were feeling. No one even hinted at giving up. Instead, everyone worked together to identify the source of each problem and then do something about it. The riders calmly coached one another on how to find relief from the heat, how to alleviate cramping, how to deal with 145-mph wobbles. The pit personnel quietly and methodically altered their procedures to handle each problem in the most logical fashion. There was no screaming and arguing. No contest of wills. No struggle of egos. Just everyone pulling in the same direction. Just teamwork.

I’m proud of the world records we set. They’re something I’ll cherish all my life. But what I’m most proud of is being a part of the team that set them—the team that worked in harmony to cash the biggest overdrawn check I had ever written. —Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

At Large

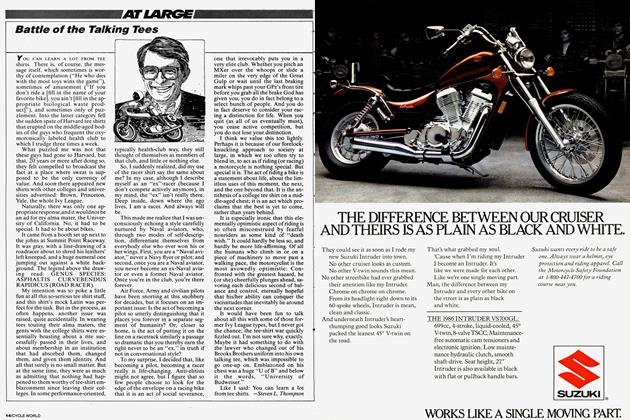

At LargeBattle of the Talking Tees

DECEMBER 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Walkman Cometh

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

DECEMBER 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

DECEMBER 1985 By Alan Cathcart -

Special Feature

Special FeatureThe Fastest Day

DECEMBER 1985 By Paul Dean