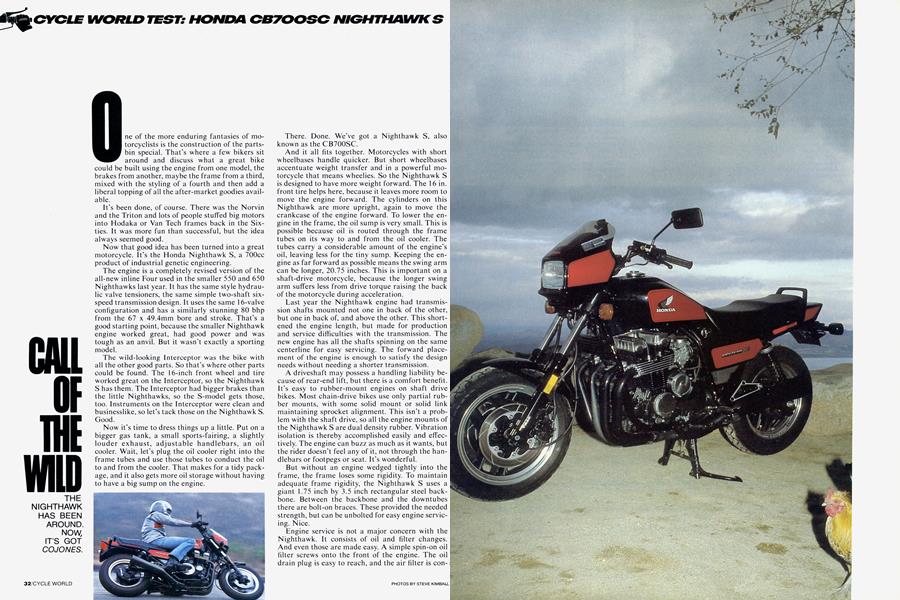

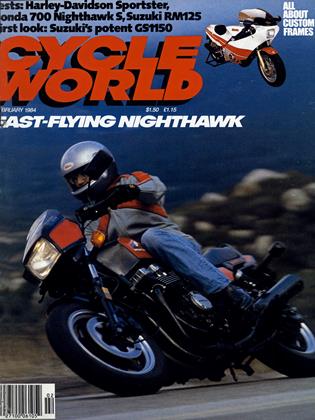

HONDA CB700SC NIGHTHAWK S

CYCLE WORLD TEST

CALL OF THE WILD

THE NIGHTHAWK HAS BEEN AROUND. NOW, IT’S GOT COJONES.

One of the more enduring fantasies of motorcyclists is the construction of the partsbin special. That’s where a few bikers sit around and discuss what a great bike could be built using the engine from one model, the brakes from another, maybe the frame from a third, mixed with the styling of a fourth and then add a liberal topping of all the after-market goodies available.

It’s been done, of course. There was the Norvin and the Triton and lots of people stuffed big motors into Hodaka or Van Tech frames back in the Sixties. It was more fun than successful, but the idea always seemed good.

Now that good idea has been turned into a great motorcycle. It’s the Honda Nighthawk S, a 700cc product of industrial genetic engineering.

The engine is a completely revised version of the all-new inline Four used in the smaller 550 and 650 Nighthawks last year. It has the same style hydraulic valve tensioners, the same simple two-shaft sixspeed transmission design. It uses the same 16-valve configuration and has a similarly stunning 80 bhp from the 67 x 49.4mm bore and stroke. That’s a good starting point, because the smaller Nighthawk engine worked great, had good power and was tough as an anvil. But it wasn’t exactly a sporting model.

The wild-looking Interceptor was the bike with all the other good parts. So that’s where other parts could be found. The 16-inch front wheel and tire worked great on the Interceptor, so the Nighthawk S has them. The Interceptor had bigger brakes than the little Nighthawks, so the S-model gets those, too. Instruments on the Interceptor were clean and businesslike, so let’s tack those on the Nighthawk S. Good.

Now it’s time to dress things up a little. Put on a bigger gas tank, a small sports-fairing, a slightly louder exhaust, adjustable handlebars, an oil cooler. Wait, let’s plug the oil cooler right into the frame tubes and use those tubes to conduct the oil to and from the cooler. That makes for a tidy package, and it also gets more oil storage without having to have a big sump on the engine.

There. Done. We’ve got a Nighthawk S, also known as the CB700SC.

And it all fits together. Motorcycles with short wheelbases handle quicker. But short wheelbases accentuate weight transfer and in a powerful motorcycle that means wheelies. So the Nighthawk S is designed to have more weight forward. The 16 in. front tire helps here, because it leaves more room to move the engine forward. The cylinders on this Nighthawk are more upright, again to move the crankcase of the engine forward. To lower the engine in the frame, the oil sump is very small. This is possible because oil is routed through the frame tubes on its way to and from the oil cooler. The tubes carry a considerable amount of the engine’s oil, leaving less for the tiny sump. Keeping the engine as far forward as possible means the swing arm can be longer, 20.75 inches. This is important on a shaft-drive motorcycle, because the longer swing arm suffers less from drive torque raising the back of the motorcycle during acceleration.

Last year the Nighthawk engine had transmission shafts mounted not one in back of the other, but one in back of, and above the other. This shortened the engine length, but made for production and service difficulties with the transmission. The new engine has all the shafts spinning on the same centerline for easy servicing. The forward placement of the engine is enough to satisfy the design needs without needing a shorter transmission.

A driveshaft may possess a handling liability because of rear-end lift, but there is a comfort benefit. It’s easy to rubber-mount engines on shaft drive bikes. Most chain-drive bikes use only partial rubber mounts, with some solid mount or solid link maintaining sprocket alignment. This isn’t a problem with the shaft drive, so all the engine mounts of the Nighthawk S are dual density rubber. Vibration isolation is thereby accomplished easily and effectively. The engine can buzz as much as it wants, but the rider doesn’t feel any of it, not through the handlebars or footpegs or seat. It’s wonderful.

But without an engine wedged tightly into the frame, the frame loses some rigidity. To maintain adequate frame rigidity, the Nighthawk S uses a giant 1.75 inch by 3.5 inch rectangular steel backbone. Between the backbone and the downtubes there are bolt-on braces. These provided the needed strength, but can be unbolted for easy engine servicing. Nice.

Engine service is not a major concern with the Nighthawk. It consists of oil and filter changes. And even those are made easy. A simple spin-on oil filter screws onto the front of the engine. The oil drain plug is easy to reach, and the air filter is con-; tained by four screws. There are no valve adjustments. The Nighthawk has hydraulic valve tensioners. Finger-type cam followers pivot on the hydraulic plungers at one end and push open the valves at the other end. The hydraulic tensioners do more than just eliminate valve adjustment. They reduce noise, maintain valve adjustment more precisely and enable the engine to use steeper cam ramps for faster valve opening. The lightweight followers also have minimal inertia, which contributes to the quick valve opening and the high operating engine speeds possible with this design. These hydraulic plugs aren’t interchangeable with the parts in the smaller Nighthawks or the Shadow or the new Gold Wing.

Hydraulic lifters rely on oil not containing air for their operation. Air bubbles in the oil would compress and not function properly, so the Nighthawk has anti-aeration chambers. Like the smaller Nighthawk, there are puddles in the cam holder caps to eliminate aeration, plus the Nighthawk S has a large container behind the cylinders, in the top of the crankcases, designed as an anti-aeration chamber. All this should eliminate any lifter aeration or pump-up.

More work has been spent on this Nighthawk to control oil aeration than was done with the first Nighthawk engine. Before, it was expected that lifter pump-up would control over-revving. Now that’s taken care of by a rev-limiter built into the ignition. Any time the engine hits l 1,500 rpm the rev limiter cuts out the ignition for one of the coils. This limiter has also found its way into other Honda designs this year, including all the V-Fours.

Just as the valve gear is a refinement on the smaller Nighthawk engine, so are most of the other design details on this bike. Valve included angle is still 38°, but now each valve is set at a 19° angle, making for simpler production. The valve sizes are bigger, naturally, because the bigger 67mm bore allows for bigger valves. Because the engine has the oil filter and cooler, a two-stage oil pump is used that sends a fraction of the oil supply through the filter, rather than all the oil. The alternator is still mounted behind the cylinders, chain driven off the crankshaft, but it is more overdriven now, uses a cam-type damper to reduce shock loads and it has additional cooling capacity for its 280-watt output.

By reconfiguring the engine drive system, the cylinders are now equally spaced, left and right, with a larger spur-cut drive gear cut into one crankshaft flywheel surface. Clutch noise is kept under control by splitting the clutch basket driven gear and spring loading the two halves. Clutch plates are 3mm wider for more surface area on the 700 than the 650. Hydraulic controls are used to disengage the clutch.

For some reason, this Nighthawk clutched and shifted more easily and precisely than the 650. The hydraulic clutch released easily and engaged predictably, with a wide enough range of engagement. The transmission shifted easily and positively. It didn’t slip out of gear. This could not be said of the smaller Nighthawk. It had a grabby clutch and as many neutrals as gears. The new Nighthawk shifts better than the smaller Nighthawk or the Interceptor.

Performance is just about what you’d expect. It’s a little quicker than the 650 and a little slower than the 750. Considering that the 650 and 750 Hondas were the quickest 650 and 750 motorcycles available last year, that’s not bad company. Our quarter-mile time was 12.00 sec. at 1 10.83 mph. That’s right on a par with the better 750s produced last year, and just a shade slower than the Honda Interceptor.

Power delivery is just as strong. There are no flat spots, or engine speeds where everything all of a sudden happens. At idle the engine runs fine. You can lug this thing around town in sixth gear no problem. But hold it in a lower gear and wind it out, and the power just keeps getting better and better. Ride it with the tach needle barely excited and it’s a wonderful around-town, just-poking-along machine. It’s not at all demanding. And then when it's time for excitement, wind it up, hold on and be thrilled. The only unusual characteristic in this, is that there’s no specific rpm where everything happens. It’s a smooth, predictable increase in power. It’s just what it’s supposed to be.

All this power is effectively used. The gear ratios are chosen to take advantage of the peak power, if not the broad power delivery. There are no wide gaps in the gears. For just transportation, the transmission has almost more gears than it needs. For acceleration, any low gear will work. And for steady-state cruising, top gear works fine, at any >

speed. You find yourself going down the highway in sixth, doing about 4500 rpm at 60 mph. Then if you need to pass someone or accelerate, you downshift two or three times and get this explosion of motion.

Braking power is at least a match for engine power. A combination of larger brake discs and the smaller front tire makes for lots of deceleration with minimal lever effort. Two fingers can lock the front tire. And when those two fingers lock the tire, some other things will be occurring. Most likely the forks will be bottomed, even with the anti-dive turned to the number four, maximum setting. But before the tire even locks, the low oil pressure warning light will come on. That new, smaller sump apparently lacks enough oil capacity or baffling to keep oil around the pick-up when the brakes are applied even moderately. Use the brakes lightly and the light stays off. But any time the Nighthawk is stopped quickly the oil pressure disappears, even when the oil level is at maximum level. Oh well, maybe there’s something in another parts bin.

The combination of chassis and suspension parts makes for handling that is very good until the limits are approached, combined with a comfortable ride. Like the other bikes recently given 16-inch front tires, steering effort is light, particularly at speed. The Nighthawk doesn’t feel like a 504 lb. motorcycle. The handlebars on the Nighthawk S are narrow, masking some of this, but it’s still easy to flick the bike back and forth. It responds well to this. Cornering clearance is great, but you still can scrape things, and that happens at the same time the rear tire has run out of traction. Now add a shaft-drive torque reaction. That complicates matters when the 700 is negotiating combinations of corners and bumps. It’s not bad, at all, it’s just not up to Interceptor standards for cornering ability.

A number of sporting shaft-drive bikes have suffered in suspension compliance for suspension control. To keep the ups and downs from disturbing the handling, it’s normal practice to increase damping. This often results in a hobby-horse ride on concrete highways with regularly spaced expansion joints. Another technique used is designing a longer swing arm. The Nighthawk has a reasonably long swing arm and the suspension is moderately compliant. It’s an excellent compromise between ride and handling, with the bike able to handle everything short of race-track demands. It’s still a little less plush than the best touring bikes, but not bad.

All those other parts that can make a motorcycle easy to live with do a good job of it on the 700. The seat is lightly stepped and well-enough padded. Two densities of foam are used for the rider’s part of the seat, and they are well chosen. The pegs are in an average position, and so are the handlebars, which are adjustable two ways. Those handlebars can also be easily replaced by normal tubular bars if a rider wants some other bend, because they are held by normal clamps. This is the best way to do adjustable bars. It’s too bad the mirrors don’t have the same range of adjustment. One rider found that when the levers were set in a comfortable position, the mirrors couldn’t be angled up enough to see behind him. His choice was to ride without serviceable mirrors or ride with the levers in an awkward position. He’s found the same problem on several other recent Hondas, but not on any other bikes.

A host of what could be called Nice Touches are found on the S. There’s a small compartment in the tailpiece, suitable for registration and maybe a couple of tools or a patch kit. Of course to reach requires seat removal and it can take 15 min. to replace the seat because of the wretched latching device. Rubber plugs fit into the heads of many alien-head bolts on the bike, including the eight bolts holding on the cam covers. They aren’t necessary, they just dress things up a little. The tool kit includes an offset screwdriver just so the rider can remove the fuse box cover more easily. Fake polished velocity stacks are visible on the outboard carbs as a styling touch. And black platic covers hide the frame in front of the gas tank and on the left side of the transmission. Sure, much of this is decoration, but that has always been part of the Nighthawk package.

What hasn’t always been Nighthawk has been performance. It is now. The Nighthawk S is probably the fastest of the new under 700cc bikes. The only 750 that can run away from it is the Interceptor.

In most ways this is not so different a bike from its 650cc predecessor, despite sharing nothing more than the final drive. It’s a Nighthawk made more useable because of the larger gas tank and more normal riding posture. The Inteceptor parts grafted on have not made it Interceptor-like to ride. Taking the best designs from the sporting Interceptor and the stylish Nighthawk 650 has made this an allaround motorcycle. There’s nothing it can’t do. E3

HONDA NIGHTHAWK S 700

SPECIFICATIONS

GENERAL

$3398

CHASSIS

SUSPENSION/ BRAKES/TIRES

ENGINE/GEARBOX

PERFORMANCE

ACCELERATION

SPEED IN GEARS

FUEL CONSUMPTION

BRAKING DISTANCE

SPEEDOMETER ERROR

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

FEBRUARY 1984 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

FEBRUARY 1984 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Book Review

FEBRUARY 1984 By Allan Girdler -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

FEBRUARY 1984 -

Features

FeaturesThe Two-Wheeled Underground Canadian Railroad

FEBRUARY 1984 By Peter Egan -

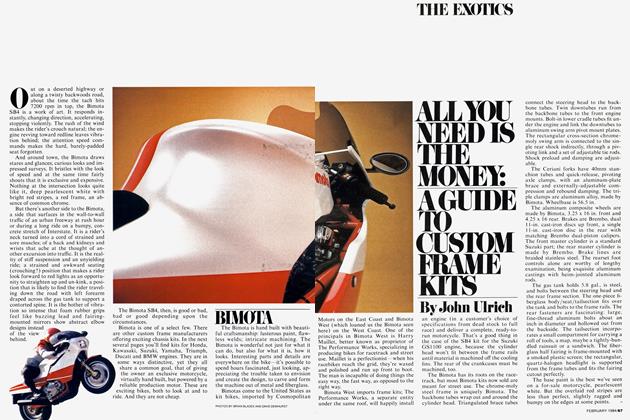

The Exotics

The ExoticsAllyou Need Is the Money

FEBRUARY 1984 By John Ulrich