KAWASAKI

PREVIEW '85

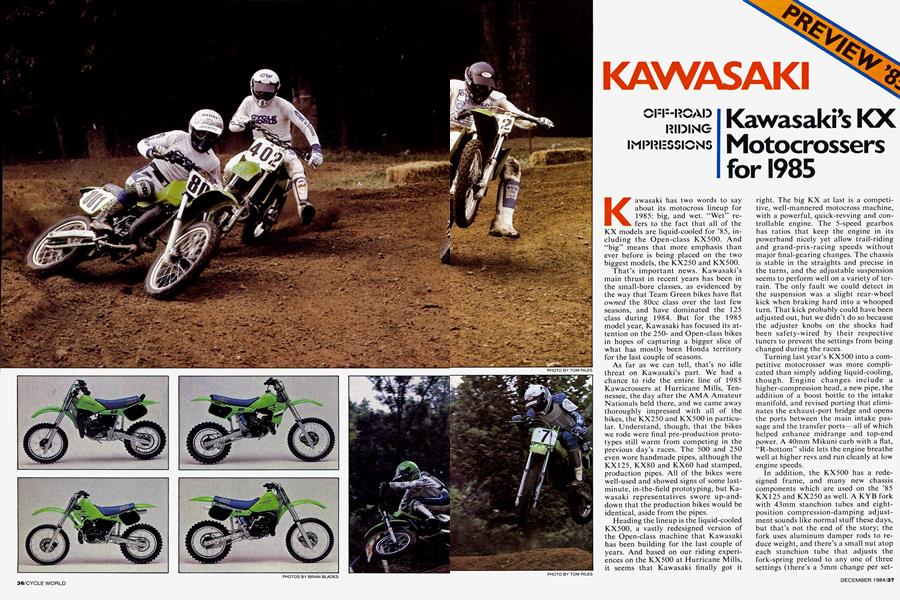

OFF-ROAD RIDING IMPRESSIONS

Kawasaki’s KX Motocrossers for 1985

Kawasaki has two words to say about its motocross lineup for 1985: big, and wet. “Wet” refers to the fact that all of the KX models are liquid-cooled for ’85, including the Open-class KX500. And “big” means that more emphasis than ever before is being placed on the two biggest models, the KX250 and KX500.

That’s important news. Kawasaki’s main thrust in recent years has been in the small-bore classes, as evidenced by the way that Team Green bikes have flat owned the 80cc class over the last few seasons, and have dominated the 125 class during 1984. But for the 1985 model year, Kawasaki has focused its attention on the 250and Open-class bikes in hopes of capturing a bigger slice of what has mostly been Honda territory for the last couple of seasons.

As far as we can tell, that’s no idle threat on Kawasaki’s part. We had a chance to ride the entire line of 1985 Kawacrossers at Hurricane Mills, Tennessee, the day after the AMA Amateur Nationals held there, and we came away thoroughly impressed with all of the bikes, the KX250 and KX500 in particular. Understand, though, that the bikes we rode were final pre-production prototypes still warm from competing in the previous day’s races. The 500 and 250 even wore handmade pipes, although the KX125, KX80 and KX60 had stamped, production pipes. All of the bikes were well-used and showed signs of some lastminute, in-the-field prototyping, but Kawasaki representatives swore up-anddown that the production bikes would be identical, aside from the pipes.

Heading the lineup is the liquid-cooled KX500, a vastly redesigned version of the Open-class machine that Kawasaki has been building for the last couple of years. And based on our riding experiences on the KX500 at Hurricane Mills, it seems that Kawasaki finally got it

right. The big KX at last is a competitive, well-mannered motocross machine, with a powerful, quick-revving and controllable engine. The 5-speed gearbox has ratios that keep the engine in its powerband nicely yet allow trail-riding and grand-prix-racing speeds without major final-gearing changes. The chassis is stable in the straights and precise in the turns, and the adjustable suspension seems to perform well on a variety of terrain. The only fault we could detect in the suspension was a slight rear-wheel kick when braking hard into a whooped turn. That kick probably could have been adjusted out, but we didn’t do so because the adjuster knobs on the shocks had been safety-wired by their respective tuners to prevent the settings from being changed during the races.

Turning last year’s KX500 into a competitive motocrosser was more complicated than simply adding liquid-cooling, though. Engine changes include a higher-compression head, a new pipe, the addition of a boost bottle to the intake manifold, and revised porting that eliminates the exhaust-port bridge and opens the ports between the main intake passage and the transfer ports—all of which helped enhance midrange and top-end power. A 40mm Mikuni carb with a flat, “R-bottom” slide lets the engine breathe well at higher revs and run cleanly at low engine speeds.

In addition, the KX500 has a redesigned frame, and many new chassis components which are used on the ’85 KX125 and KX250 as well. A KYB fork with 43mm stanchion tubes and eightposition compression-damping adjustment sounds like normal stuff these days, but that’s not the end of the story; the fork uses aluminum damper rods to reduce weight, and there’s a small nut atop each stanchion tube that adjusts the fork-spring preload to any one of three settings (there’s a 5mm change per setting). The fork sliders don’t project below the axle as far, so they don’t drag in deep grooves as easily, and there’s about 1.5 inches more engagement between the sliders and the stanchion tubes.

The rear suspension is equally slick. A new KYB shock features separately adjustable highand low-speed compression damping, with four positions for each. The rebound damping also is fourposition-adjustable, and the aluminum Uni-Trak link (the vertical strut that connects the swingarm to the suspension rocker) can be adjusted for length. Kawasaki says the link adjustment is primarily to allow parts interchangeability between 125, 250 and Open bikes, and also so an owner can adjust the clearance between the top of the rear tire and the inside of the rear fender (handy when changing to a tire with a different profile). The adjustable link isn’t meant as a means of altering the seat height or steering geometry. Rear wheel travel is now claimed to be 12.6 inches.

Other parts shared by the KX125, 250 and 500 include: a larger, drilled front brake disc; a master cylinder with a oneway valve that simplifies brake-bleeding; an improved seal on the rear-brake backing plate; larger axles front and rear (up from 15mm to 17mm in front, and from 17mm to 20mm in the rear); a new airbox that takes in air up under the fuel tank; offset, rubber-mounted handlebar pedestals that can be used with the offset facing either forward or toward the rear; and a new clutch that separates the kickstart gear from the primary-drive gear, thereby eliminating clutch-chatter when coming off the starting line at high revs. And cosmetically, the 125, 250 and 500 all get new side numberplates, a new seat with a seamless blue cover, and a more conventional rear fender than those used on previous models.

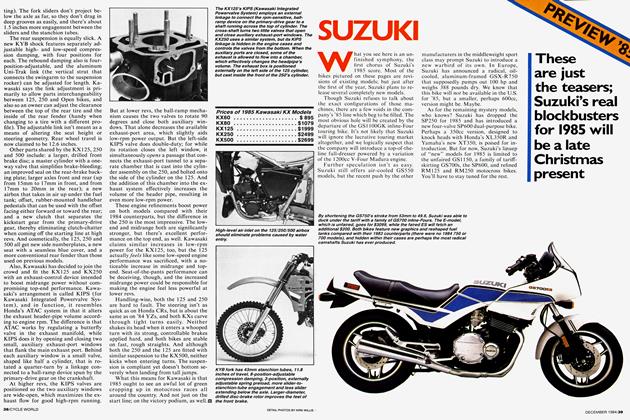

Also, Kawasaki has decided to join the crowd and fit the KX125 and KX250 with an exhaust-control device intended to boost midrange power without compromising top-end performance. Kawasaki’s arrangement is called KIPS (for Kawasaki Integrated Powervalve System), and in function, it resembles Honda’s ATAC system in that it alters the exhaust header-pipe volume according to engine rpm. The difference is that ATAC works by regulating a butterfly valve in the exhaust manifold, while KIPS does it by opening and closing two small, auxiliary exhaust-port windows that flank the main exhaust port. Behind each auxiliary window is a small valve, shaped like half a cylinder, that is rotated a quarter-turn by a linkage connected to a ball-ramp device spun by the primary-drive gear on the crankshaft.

At higher revs, the KIPS valves are positioned so the two auxiliary windows are wide-open, which maximizes the exhaust flow for good high-rpm running.

But at lower revs, the ball-ramp mechanism causes the two valves to rotate 90 degrees and close both auxiliary windows. That alone decreases the available exhaust-port area, which slightly aids low-rpm power output. But the left-side KIPS valve does double-duty; for while its rotation closes the left window, it simultaneously opens a passage that connects the exhaust-port tunnel to a separate chamber that is cast into the cylinder assembly on the 250, and bolted onto the side of the cylinder on the 125. And the addition of this chamber into the exhaust system effectively increases the volume of the header pipe, resulting in even more low-rpm power.

These engine refinements boost power on both models compared with their

1984 counterparts, but the difference in the 250 is the most impressive. The lowend and midrange both are significantly stronger, but there’s excellent performance on the top end, as well. Kawasaki claims similar increases in low-rpm power for the KX125, too, but the 125 actually feels like some low-speed engine performance was sacrificed, with a noticeable increase in midrange and topend. Seat-of-the-pants performance can be deceiving, though, and the increased midrange power could be responsible for making the engine feel less powerful at lower revs.

Handling-wise, both the 125 and 250 are hard to fault. The steering isn’t as quick as on Honda CRs, but is about the same as on ’84 YZs, and both KXs carve through tight turns easily. Neither shakes its head when it enters a whooped turn with its strong, controllable brakes applied hard, and both bikes are stable on fast, rough straights. And although both the 250 and the 125 are fitted with similar suspension to the KX500, neither kicks when entering turns. The suspension is compliant yet doesn’t bottom severely when landing from tall jumps.

What this means for Kawasaki is that 1985 ought to see an awful lot of green cropping up in motocross races all around the country. And not just on the start line; on the victory podium, as well.O

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Editorial

DECEMBER 1984 By Paul Dean -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

DECEMBER 1984 -

Departments

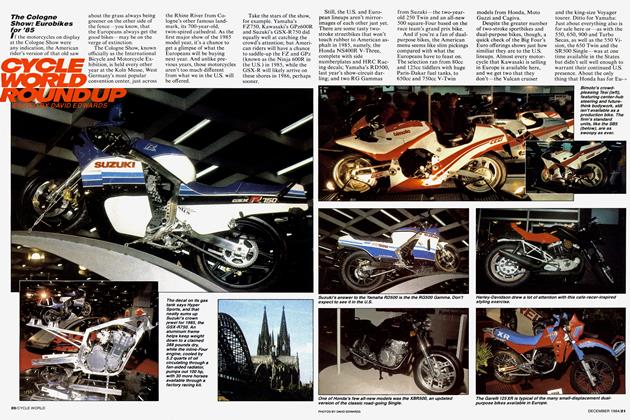

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

DECEMBER 1984 By David Edwards -

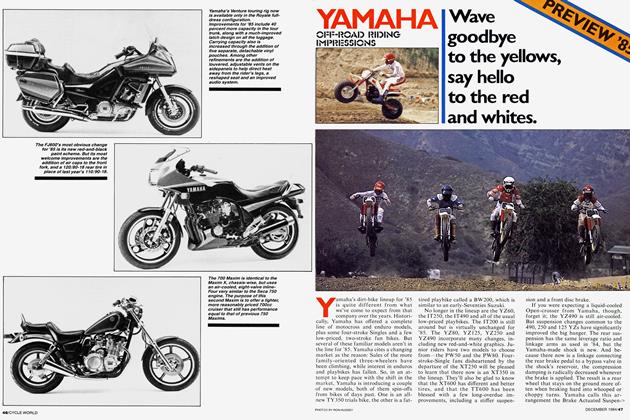

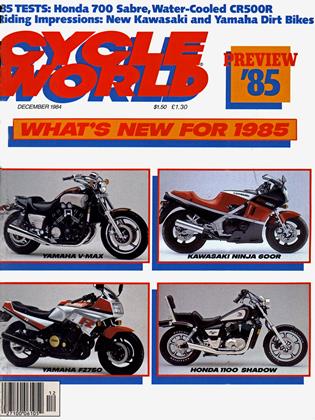

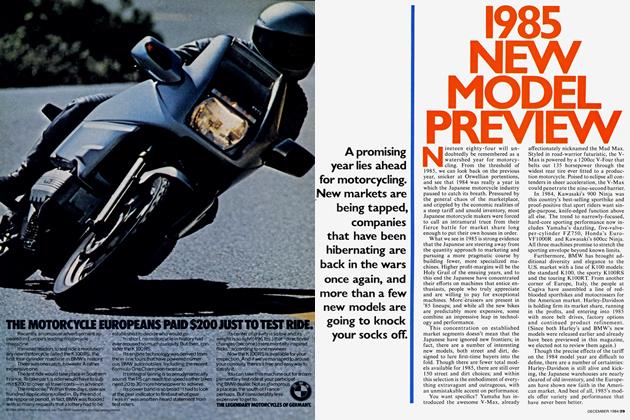

Preview '85

Preview '851985 New Model Preview

DECEMBER 1984 -

Departments

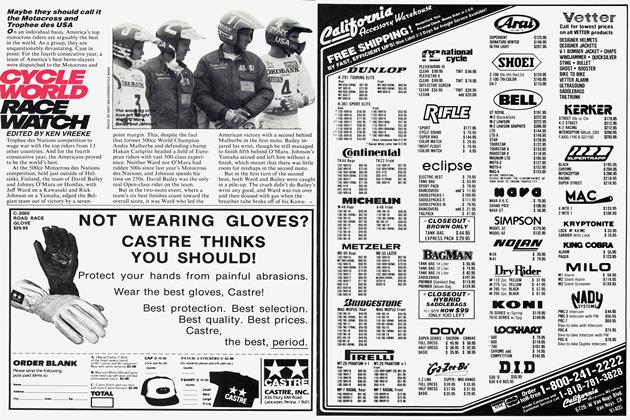

DepartmentsCycle World Race Watch

DECEMBER 1984 By Ken Vreeke -

Departments

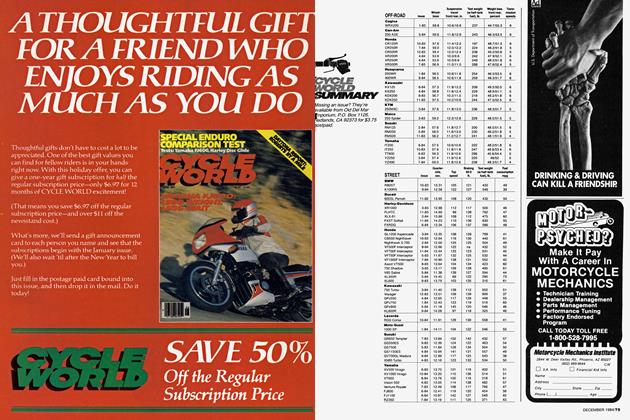

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

DECEMBER 1984