YAMAHA TT600

CYCLE WORLD TEST:

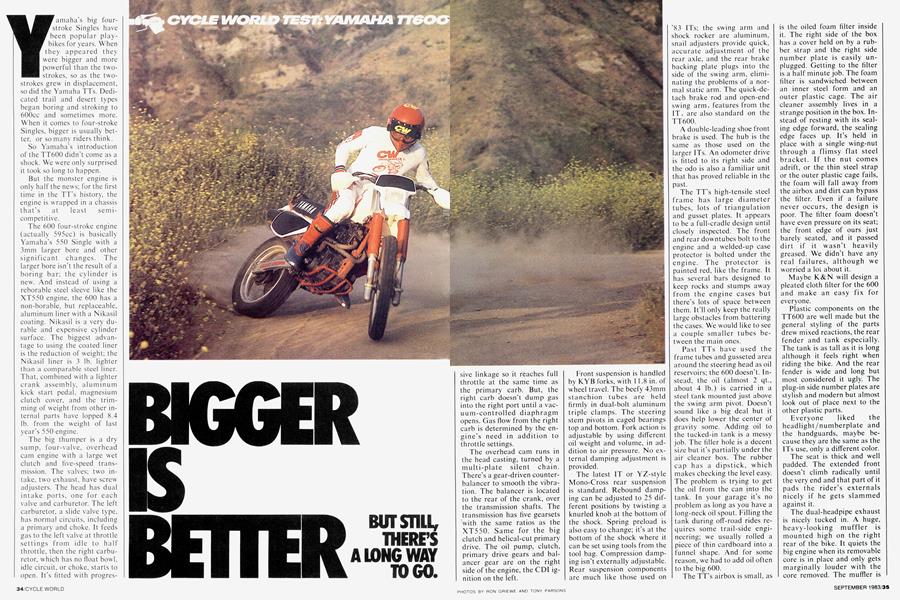

BIGGER IS BETTER BUT STILL, THERE'S A LONG WAY TO GO.

Yamaha's big fourstroke Singles have been popular playbikes for years. When they appeared the were bigger and more powerful than the twostrokes, so as the twostrokes grew in displacement. so did the Yamaha TTs. Dedi cated trail and desert types began boring and stroking to 600cc and sometimes more. When it comes to four-stroke Singles, bigger is usually bet ter, or so many riders think.

So Yamaha's introduction of the TT600 didn't come as a shock. W/e were only surprised it took so long to happen.

But the monster engine is only half the news; for the first time in the TT's history, the engine is wrapped in a chassis that's at least semicompetitive.

The 600 four-stroke engine (actually 595cc) is basically Yamaha’s 550 Single with a 3mm larger bore and other significant changes. The larger bore isn't the result of a boring bar; the cylinder is new. And instead of using a reborable steel sleeve like the XT550 engine, the 600 has a non-borable, but replaceable, aluminum liner with a Nikasil coating. Nikasil is a very durable and expensive cylinder surface. The biggest advantage to using the coated liner is the reduction of weight; the Nikasil liner is 3 lb. lighter than a comparable steel liner. That, combined with a lighter crank assembly, aluminum kick start pedal, magnesium clutch cover, and the trimming of weight from other internal parts have lopped 8.4 lb. from the weight of last year’s 550 engine.

The big thumper is a dry sump, four-valve, overhead cam engine with a large wet clutch and five-speed transmission. The valves; two intake, two exhaust, have screw adjusters. The head has dual intake ports, one for each valve and carburetor. The left carburetor, a slide valve type, has normal circuits, including a primary and choke. It feeds gas to the left valve at throttle settings from idle to half throttle, then the right carburetor, which has no float bowl, idle circuit, or choke, starts to open. It’s fitted with progres-

sive linkage so it reaches full throttle at the same time as the primary carb. But, the right carb doesn’t dump gas into the right port until a vacuum-controlled diaphragm opens. Gas flow from the right carb is determined by the engine’s need in addition to throttle settings.

The overhead cam runs in the head casting, turned by a multi-plate silent chain. There’s a gear-driven counterbalancer to smooth the vibration. The balancer is located to the rear of the crank, over the transmission shafts. The transmission has five gearsets with the same ratios as the XT550. Same for the big clutch and helical-cut primary drive. The oil pump, clutch, primary drive gears and balancer gear are on the right side of the engine, the CD! ignition on the left. Front suspension is handled by KYB forks, with 11.8 in. of wheel travel. The beefy 43mm stanchion tubes are held firmly in dual-bolt aluminum triple clamps. The steering stem pivots in caged bearings top and bottom. Fork action is adjustable by using different oil weight and volume, in addition to air pressure. No external damping adjustment is provided.

The latest IT or YZ-style Mono-Cross rear suspension is standard. Rebound damping can be adjusted to 25 different positions by twisting a knurled knob at the bottom of the shock. Spring preload is also easy to change; it's at the bottom of the shock where it can be set using tools from the tool bag. Compression damping isn't externally adjustable. Rear suspension components are much like those used on '83 ITs; the swing arm and shock rocker are aluminum, snail adjusters provide quick, accurate adjustment of the rear axle, and the rear brake backing plate plugs into the side of the swing arm, eliminating the problems of a normal static arm. The quick-detach brake rod and open-end swing arm, features from the IT, are also standard on the TT600.

A double-leading shoe front brake is used. The hub is the same as those used on the larger ITs. An odometer drive is fitted to its right side and the odo is also a familiar unit that has proved reliable in the past.

The TT’s high-tensile steel frame has large diameter tubes, lots of triangulation and gusset plates. It appears to be a full-cradle design until closely inspected. The front and rear downtubes bolt to the engine and a welded-up case protector is bolted under the engine. The protector is painted red, like the frame. It has several bars designed to keep rocks and stumps away from the engine cases but there’s lots of space between them. It'll only keep the really large obstacles from battering the cases. We would like to see a couple smaller tubes between the main ones.

Past TTs have used the frame tubes and gusseted area around the steering head as oil reservoirs; the 600 doesn’t. Instead, the oil (almost 2 qt., about 4 lb.) is carried in a steel tank mounted just above the swing arm pivot. Doesn’t sound like a big deal but it does help lower the center of gravity some. Adding oil to the tucked-in tank is a messy job. The filler hole is a decent size but it's partially under the air cleaner box. The rubber cap has a dipstick, which makes checking the level easy. The problem is trying to get the oil from the can into the tank. In your garage it's no problem as long as you have a long-neck oil spout. Filling the tank during off-road rides requires some trail-side engineering; we usually rolled a piece of thin cardboard into a funnel shape. And for some reason, we had to add oil often to the big 600.

The TT's airbox is small, as is the oiled foam filter inside it. The right side of the box has a cover held on by a rubber strap and the right side number plate is easily unplugged. Getting to the filter is a half minute job. The foam filter is sandwiched between an inner steel form and an outer plastic cage. The air cleaner assembly lives in a strange position in the box. Instead of resting with its sealing edge forward, the sealing edge faces up. It’s held in place with a single wing-nut through a flimsy flat steel bracket. If the nut comes adrift, or the thin steel strap or the outer plastic cage fails, the foam will fall away from the airbox and dirt can bypass the filter. Even if a failure never occurs, the design is poor. The filter foam doesn't have even pressure on its seat; the front edge of ours just barely seated, and it passed dirt if it wasn't heavily greased. We didn't have any real failures, although we worried a lot about it.

Maybe K&N will design a pleated cloth filter for the 600 and make an easy fix for everyone.

Plastic components on the TT600 are well made but the general styling of the parts drew mixed reactions, the rear fender and tank especially. The tank is as tall as it is long although it feels right when riding the bike. And the rear fender is wide and long but most considered it ugly. The plug-in side number plates are stylish and modern but almost look out of place next to the other plastic parts.

Everyone liked the headlight/numberplate and the handguards, maybe because they are the same as the ITs use, only a different color.

The seat is thick and well padded. The extended front doesn't climb radically until the very end and that part of it pads the rider's externals nicely if he gets slammed against it.

The dual-headpipe exhaust is nicely tucked in. A huge, heavy-looking muffler is mounted high on the right rear of the bike. It quiets the big engine when its removable core is in place and only gets marginally louder with the core removed. The muffler is

equipped with a spark arrester but strangely, the spark arrester parts are connected to the removable core so removing the silencer core also removes the spark arrester.

The TT600 has a fairly low, 36.8 in. seat height unladen. With a rider aboard the bike’s soft suspension allows more squat than normal, lowering actual height even more. Bouncing on the bike and trying the fit quickly tells you the TT600 doesn’t feel like modern dirt bikes normally feel. The bars are a high-rise bend, the gas tank sits high, the unequal wheel travel lets the front sit much higher than the rear, and the suspension at both ends has such soft springs, half of the travel is used up in sack.

Starting the TT600 is easier than you might expect. The forged aluminum kick lever is long, leverage is good, and the right footpeg perch is designed so the kicker can travel to a full bottom position. The automatic decompression device is actuated when the kick lever starts down and also eases the kicking pressure. Unfortunately, the bike isn’t fitted with a manual decompression lever like the XT550. If the engine gets flooded from kicking too easily or from falling over, you can’t pull a lever and clear the gas from the combustion chamber. If either happens, you’ll wear out your whole riding group before you get the bike running again. Otherwise, the bike isn’t too difficult to start. Two or three brisk kicks when cold, one or two when hot.

The engine warms up quickly and runs smoothly, with just a hint of a thump. The counterbalancer does a nice job of smoothing the vibration while still letting enough boom through to know you’re on a big lunger. The transmission drops into gear without a lot of noise or resistance and the clutch engages smoothly and progressively. There’s no forward lurch as the clutch releases, the bike just starts to move away smoothly. Shifts are smooth and precise and the gear spacing is perfect for the engine’s power and torque. And torque is what this engine is all about. Power is plentiful at lower

revs but it flattens suddenly if the rider tries to rev it. Short shifting is the only way to ride this bike. Wringing it out only produces noise. All of the power is made at low revs. You want a bike to plunk through the trees or hills with? This is it.

Riding a new XR500R Honda, then a TT600 would have most betting the easyrevving Honda is faster. Not so. They are within inches of each other in a drag with equal weight and ability riders. You hear a lot about how well big four-stroke Singles climb hills. The TT600 really does,mostly in second gear. It’ll just plunk on up while sounding as though it’s idling. Coming down steep hills is equally fun. The big engine holds the speed of the bike to reasonable speeds and keeps it straight with a slight touch of the brakes now and then.

If you fall over you’ll know the bike is heavy. It weighs 296 lb. with the gas tank half-full.

Handling through bumpy terrain is disappointing. The too-soft suspension lets the bike bob and weave badly. The limited rear wheel travel, soft shock spring and bulk of the 600 means the back of the bike bottoms in every depression. There’s a constant banging at the rear of the bike at anything but the most modest trail speed. Setting rear spring preload to maximum and adding a couple of clicks more rebound damping helped, but didn’t cure the problem. The standard spring is way too soft. A heavier spring would help, as would externally adjustable compression damping, not standard on the TT.

The fork springs let the front of the bike droop badly. It also bottoms but 11.8 in. of travel reduces the banging. Trail-side fixes are also easier. We added 6 psi to the forks, which stopped the bottoming.

These changes made the TT600 better but it still wanders on tight trails and had a generally spongy feel to the suspension.

Stiffer springs for both ends of the TT600 should improve the suspension. Only fork springs were available at the time of the test, and that alone would not solve the problems.

Until we have a chance to try the bike with stiffer springs, we won’t know if they are the solution. As it is, the TT600 has suspension more suited to casual trail riding than high speed competition.

The TT600 is a natural slider. Flat-tracking fire roads is a ball until a rain rut is crossed, then the back bottoms and the bike wallows. And with the too-soft suspension the bike doesn’t have good straight-line manners. It weaves around and generally has a better-not-push-it feel.

Most riders were comfort-

able with the seat/footpeg/ control placement. Some didn’t like the tall handlebars, some did. The bike is narrow in the middle and easy to move around on. The only thing that touches the rider while moving fore and aft is the kick start lever. It doesn’t tuck in as tightly as it should. Some of our riders, the ones who hug the bike tightly with their legs, voiced concern about catching the kick lever with their boot or lower leg, dragging the lever to the rear where it would try to engage. It never actually engaged but the noise of the kick start gears spinning against each other with the engine turning 5000 rpm frightened a couple of riders. If the mechanism does engage at such an rpm . . . have a lot of money in the bank to replace the exploded parts.

We put 1400 mi. on the test bike in a variety of terrain. It never failed to start, or to run all day. Ridden at a medium fast pace the bike will go 80 to 90 mi. before refueling. Faster speeds, not possible until the stiffer suspension gets here, will probably shorten that distance some.

All in all, we like the TT600. But, it’s a shame it needs so much work. Motorcycles shouldn’t need different springs before being right for average weight riders. Changing a tire or two isn’t that much of a problem, trying to get stiffer springs usually is. And to be truly competitive with other ’83 four-stroke Singles, the TT600 should have a shock with adjustable compression damping as well.

Meanwhile, the TT600 is close to being what it should be.

SPECIFICATIONS

$2299

Yamaha Motor Corp.,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Broken String

September 1983 -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

September 1983 -

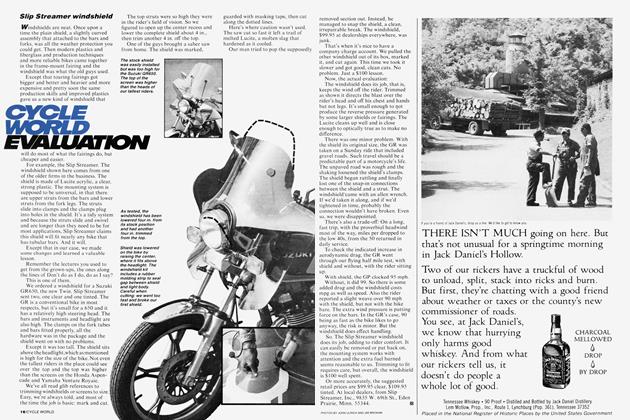

Cycle World Evaluation

Cycle World EvaluationSlip Streamer Windshield

September 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Book Reviews

September 1983 By John Ulrich -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

September 1983 -

Features

FeaturesHeartfelt Highways

September 1983 By Wade Roberts