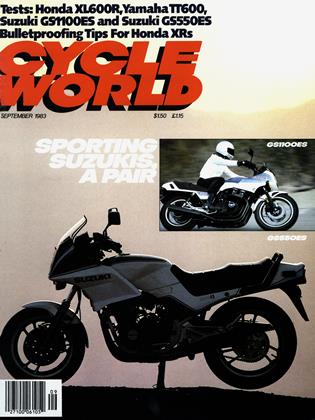

SUZUKI GS55OES

CYCLE WORLD TEST:

WIND IT UP... WAICH IT GO.

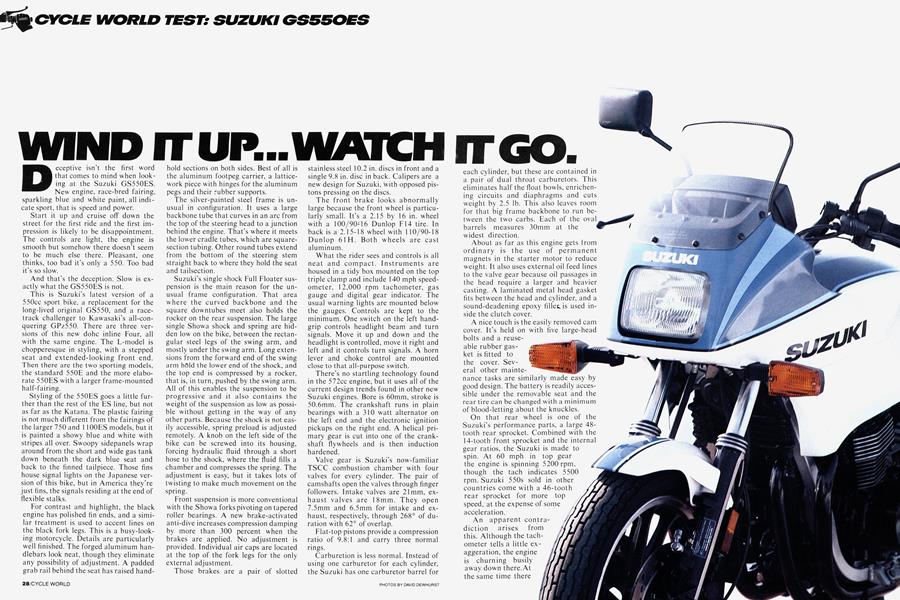

Deceptive isn't the first word that comes to mind when looking at the Suzuki GS550ES. New engine, race-bred fairing, sparkling blue and white paint, all indicate sport, that is speed and power.

Start it up and cruise off down the street for the first ride and the first impression is likely to be disappointment. The controls are light, the engine is smooth but somehow there doesn’t seem to be much else there. Pleasant, one thinks, too bad it’s only a 550. Too bad it’s so slow.

And that’s the deception. Slow is exactly what the GS550ES is not.

This is Suzuki’s latest version of a 550cc sport bike, a replacement for the long-lived original GS550, and a racetrack challenger to Kawasaki’s all-conquering GPz550. There are three versions of this new dohc inline Four, all with the same engine. The L-model is chopperesque in styling, with a stepped seat and extended-looking front end. Then there are the two sporting models, the standard 550E and the more elaborate 550ES with a larger frame-mounted half-fairing.

Styling of the 550ES goes a little further than the rest of the ES line, but not as far as the Katana. The plastic fairing is not much different from the fairings of the larger 750 and 1 100ES models, but it is painted a showy blue and white with stripes all over. Swoopy sidepanels wrap around from the short and wide gas tank down beneath the dark blue seat and back to the finned tailpiece. Those fins house signal lights on the Japanese version of this bike, but in America they’re just fins, the signals residing at the end of flexible stalks.

For contrast and highlight, the black engine has polished fin ends, and a similar treatment is used to accent lines on the black fork legs. This is a busy-looking motorcycle. Details are particularly well finished. The forged aluminum handlebars look neat, though they eliminate any possibility of adjustment. A padded grab rail behind the seat has raised hand-

hold sections on both sides. Best of all is the aluminum footpeg carrier, a latticework piece with hinges for the aluminum pegs and their rubber supports.

The silver-painted steel frame is unusual in configuration. It uses a large backbone tube that curves in an arc from the top of the steering head to a junction behind the engine. That's where it meets the lower cradle tubes, which are squaresection tubing. Other round tubes extend from the bottom of the steering stem straight back to where they hold the seat and tailsection.

Suzuki’s single shock Full Floater suspension is the main reason for the unusual frame configuration. That area where the curved backbone and the square downtubes meet also holds the rocker on the rear suspension. The large single Showa shock and spring are hidden low on the bike, between the rectangular steel legs of the swing arm, and mostly under the swing arm. Long extensions from the forward end of the swing arm hold the lower end of the shock, and the top end is compressed by a rocker, that is, in turn, pushed by the swing arm. All of this enables the suspension to be progressive and it also contains the weight of the suspension as low as possible without getting in the way of any other parts. Because the shock is not easily accessible, spring preload is adjusted remotely. A knob on the left side of the bike can be screwed into its housing, forcing hydraulic fluid through a short hose to the shock, where the fluid fills a chamber and compresses the spring. The adjustment is easy, but it takes lots of twisting to make much movement on the spring.

Front suspension is more conventional with the Showa forks pivoting on tapered roller bearings. A new brake-activated anti-dive increases compression damping by more than 300 percent when the brakes are applied. No adjustment is provided. Individual air caps are located at the top of the fork legs for the only external adjustment.

Those brakes are a pair of slotted

stainless steel 10.2 in. discs in front and a single 9.8 in. disc in back. Calipers are a new design for Suzuki, with opposed pistons pressing on the discs.

The front brake looks abnormally large because the front wheel is particularly small. It’s a 2.15 by 16 in. wheel with a 100/90-16 Dunlop F14 tire. In back is a 2.15-18 wheel with 110/90-18 Dunlop 61H. Both wheels are cast aluminum.

What the rider sees and controls is all neat and compact. Instruments are housed in a tidy box mounted on the top triple clamp and include 140 mph speedometer, 12,000 rpm tachometer, gas gauge and digital gear indicator. The usual warning lights are mounted below the gauges. Controls are kept to the minimum. One switch on the left handgrip controls headlight beam and turn signals. Move it up and down and the headlight is controlled, move it right and left and it controls turn signals. A horn lever and choke control are mounted close to that all-purpose switch.

There’s no startling technology found in the Slice engine, but it uses all of the current design trends found in other new Suzuki engines. Bore is 60mm, stroke is 50.6mm. The crankshaft runs in plain bearings with a 310 watt alternator on the left end and the electronic ignition pickups on the right end. A helical primary gear is cut into one of the crankshaft flywheels and is then induction hardened.

Valve gear is Suzuki’s now-familiar TSCC combustion chamber with four valves for every cylinder. The pair of camshafts open the valves through finger followers. Intake valves are 21mm, exhaust valves are 18mm. They open 7.5mm and 6.5mm for intake and exhaust, respectively, through 268° of duration with 62° of overlap.

Flat-top pistons provide a compression ratio of 9.8:1 and carry three normal rings.

Carburetion is less normal. Instead of using one carburetor for each cylinder, the Suzuki has one carburetor barrel for each cylinder, but these are contained in a pair of dual throat carburetors. This eliminates half the float bowls, enrichening circuits and diaphragms and cuts weight by 2.5 lb. This also leaves room for that big frame backbone to run between the two carbs. Each of the oval barrels measures 30mm at the < widest direction.

About as far as this engine gets from ordinary is the use of permanent magnets in the starter motor to reduce weight. It also uses external oil feed lines to the valve gear because oil passages in the head require a larger and heavier casting. A laminated metal head gasket fits between the head and cylinder, and a sound-deadening epoxy filler, is used inside the clutch cover.

A nice touch is the easily removed cam cover. It’s held on with five large-head bolts and a reuseable rubber gasket is fitted to the cover. Several other mainte^Jr nance tasks are similarly made easy by good design. The battery is readily accessible under the removable seat and the rear tire can be changed with a minimum of blood-letting about the knuckles.

On that rear wheel is one of the Suzuki’s performance parts, a large 48tooth rear sprocket. Combined with the 14-tooth front sprocket and the internal gear ratios, the Suzuki is made to spin. At 60 mph in top gear the engine is spinning 5200 rpm, though the tach indicates 5500 rpm. Suzuki 550s sold in other countries come with a 46-tooth rear sprocket for more top speed, at the expense of some acceleration.

An apparent contradiction arises from this. Although the tachometer tells a little exaggeration, the engine is churning busily away down there. At the same time there

is no feeling of strain. The bars buzz, the mirrors fuzz and the engine sounds as if there should be one more gear to go, except that the engine isn’t working hard and the rider quickly becomes accustomed to the revs.

This gearing works with the engine’s two-stage powerband. The bike pulls away from stops at 2000 rpm and, if the rider wants to try it, will lug down to 1000 rpm in 6th and accelerate smoothly from there well past redline with no jerks or hesitation. Normal brisk city riding doesn’t demand more than 5000 to 6000 rpm between shifts, and launching from stops at 3000 rpm leaves traffic far behind.

Take the tach over 8000 rpm and the Suzuki changes character. There’s a flatness to the throttle below that, but over 8000 rpm the bike comes alive and pulls, the gearbox ratios working perfectly to keep the engine on song. At the dragstrip the Suzuki keeps demanding upshifts, like a racebike on a straightaway. The gearing, the power above 8000 rpm and the easy-to-control clutch with a wide engagement point all contribute to the Suzuki’s brilliant dragstrip performance. In seven quarter-mile runs the GS550 always ran between 12.55 and 12.39 sec. with terminal speeds between 106.76 and 105.75 mph.

Top speed is no less spectacular. The GS will pull redline in 6th with the rider sitting bolt upright and it will rev well past redline with the rider tucked in. At the 10,000 rpm redline the Suzuki is doing 116 mph. In a half-mile run to top speed, though, the 550 registered 124 mph on the calibrated radar gun.

To put these numbers in perspective, consider the performance of last year’s GPz550, the fastest bike in the class at that time. It had a top speed of 116 mph and a quarter-mile time of 12.70 sec. at 102.04 mph.

The Suzuki’s suspension is as sporting as its powertrain. The ride is firm, making the bike choppy on some freeways, but it never intrudes on ordinary roads. This is easily the lightest steering, quickest handling 550. It is stable at speed, and the suspension keeps the wheels on the ground.

Quick steering does not, by itself, make for an enjoyable to ride motorcycle. There are bikes that can be difficult to control because they overreact to rider controls. The GS550 isn’t like that. It turns with minimal effort and does so immediately, but it doesn’t do more than it is asked to do.

It may be tempting to credit the 16 in. front wheel with the light, stable steering, but that wouldn’t be fair. Sure, all the new bikes equipped with 16 in. front wheels have been responsive and stable, but there’s more to it than the 16 in. front tire. The small tire with a short contact patch was just one of the tools the chassis designers used to achieve the handling they sought. Rake and trail were reduced. Tire profile and construction has been tailored just for some of the new bikes. If you want to assign credit, assign it to the designers who juggled the compromises to give both quick steering and stability at the same time, not just to the most obvious tools that they used.

In its first race in the west coast’s hotly-competitive AFM 600cc Production class at Sears Point in California, a GS550ES won. Rider Tom Chew set up his bike with maximum rear preload and fork air pressure at 15 psi for the best cornering clearance, and the Suzuki was the only bike on the track that didn’t show daylight under its wheels as it crossed the rough pavement at the startfinish line. With the stands removed, Chew dragged the head pipe heat shields on both sides of the bike and the sidestand bracket on the left side.

On the street it takes hard riding to drag anything, and before that the stock tires slide. Replacing the stock tires not only improves the cornering ability, it can help braking ability.

The brakes on the 550 are markedly better than the brakes on other Suzukis with anti-dive. Since Suzuki has started installing the brake-controlled anti-dive, their bikes have lost brake feel and controllability. The new opposed piston calipers restore the excellent brake feel.

Riding the GS550ES is a pleasant experience. The seating position is comfortable for most riders, though the strut-type handlebars eliminate any adjustment. The seat is wide but hard and becomes noticeable after 30 or 40 min. The controls work with moderate effort,

though the clutch suffered during the dragstrip testing and shifting became harder after that.

When it’s time to turn the petcock onto reserve, the Suzuki’s biggest nuisance becomes apparent. The petcock is hidden behind a small door on the left sidecover and riders couldn't open the door while wearing heavy gloves, this forced riders to pull off the left glove and wedge it under a knee, open the door, turn the petcock, close the door and put on the glove again. This is silly.

At least the Suzuki had an adequate range before needing reserve, running at ldast 170 mi. when ridden hard, and going 2 00 mi. at a more moderate pace. Mileage was 54 mpg on the test loop.

The two-barrel carburetors, which may well be lighter and more compact than a set of four single-barrel carbs, do not provide ideal carburetion. The GS550ES is the most cold-blooded and

reluctant to start and run bike since, well, last year’s GS550. It takes full choke to start and the choke must remain on for several miles. During that time the bike starves and misses and dies a couple of times when the brakes are applied and it floods. Even after five or six min. of running the carburetion is still lean off idle and the bike surges at small throttle openings.

Once warmed up and running at a good clip, the Suzuki GS550ES is up to its assigned task of taking on Kawasaki’s 550 for the middleweight performance championship. It steers with less effort than anything else its size. It looks racy and has handling to match the looks. Its styling doesn’t interfere with performance, nor does its styling force the rider to put up with discomfort for fashion’s sake.

The Suzuki is made for riding, and riding hard.

SPECIFICATIONS

$2999

U.S. Suzuki Motor Corp.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Broken String

September 1983 -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

September 1983 -

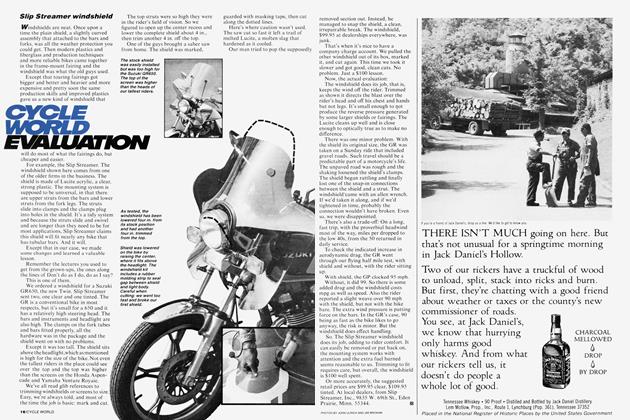

Cycle World Evaluation

Cycle World EvaluationSlip Streamer Windshield

September 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Book Reviews

September 1983 By John Ulrich -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

September 1983 -

Features

FeaturesHeartfelt Highways

September 1983 By Wade Roberts