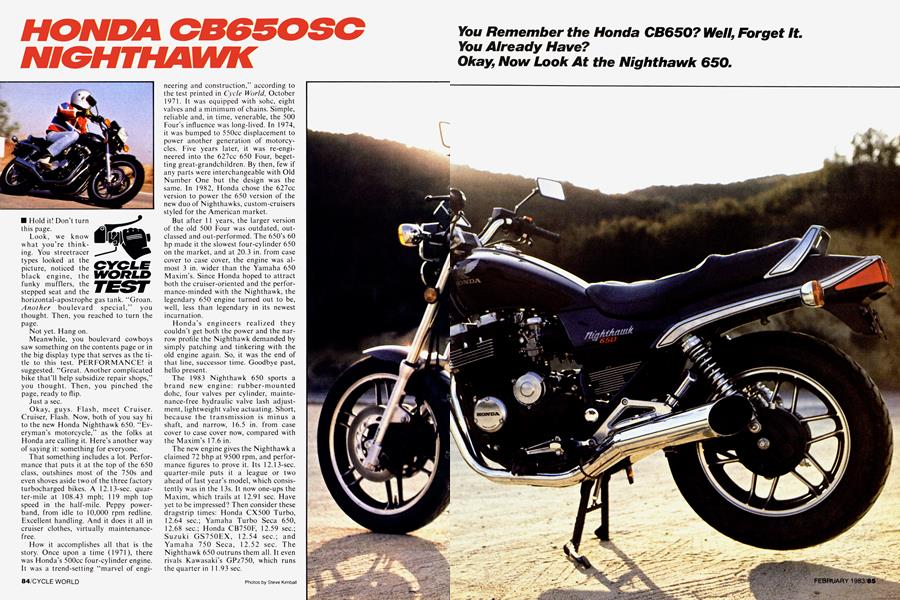

HONDA CB650SC NIGHTHAWK

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Hold it! Don't turn this page.

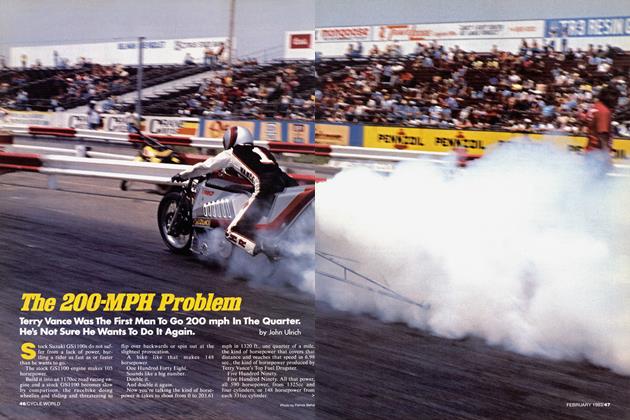

Look, we know what you're thinking. You streetracer types looked at the picture, noticed the black engine, the funky mufflers, the stepped seat and the

horizontal-apostrophe gas tank. "Groan. Another boulevard special," you thought. Then, you reached to turn the page.

Not yet. Hang on.

Meanwhile, you boulevard cowboys saw something on the contents page or in the big displav type that serves as the title to this test. PERFORMANCE! it suggested. “Great. Another complicated bike that’ll help subsidize repair shops,” you thought. Then, you pinched the page, ready to flip.

Just a sec.

Okay, guys. Flash, meet Cruiser. Cruiser, Flash. Now, both of you say hi to the new Honda Nighthawk 650. “Everyman’s motorcycle,” as the folks at Honda are calling it. Here’s another way of saying it: something for everyone.

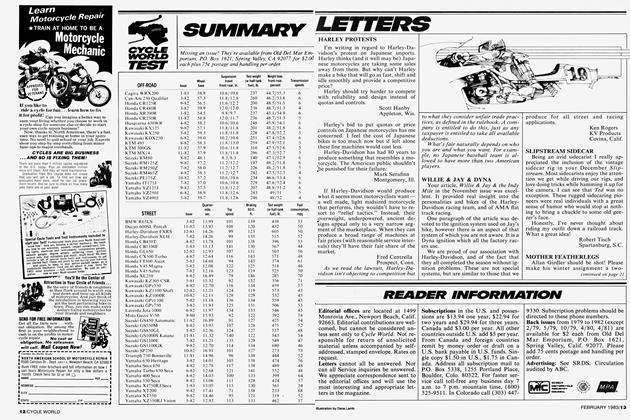

That something includes a lot. Performance that puts it at the top of the 650 class, outshines most of the 750s and even shoves aside two of the three factory turbocharged bikes. A 12.13-sec. quarter-mile at 108.43 mph; 119 mph top speed in the half-mile. Peppy powerband, from idle to 10,000 rpm redline. Excellent handling. And it does it all in cruiser clothes, virtually maintenancefree.

How it accomplishes all that is the story. Once upon a time (1971), there was Honda's 500cc four-cylinder engine. It was a trend-setting “marvel of engineering and construction,” according to the test printed in Cycle World, October 1971. It was equipped with sohc, eight valves and a minimum of chains. Simple, reliable and, in time, venerable, the 500 Four’s influence was long-lived. In 1974, it was bumped to 550cc displacement to power another generation of motorcycles. Five years later, it was re-engineered into the 627cc 650 Four, begetting great-grandchildren. By then, few if any parts were interchangeable with Old Number One but the design was the same. In 1982, Honda chose the 627cc version to power the 650 version of the new duo of Nighthawks, custom-cruisers styled for the American market.

But after 11 years, the larger version of the old 500 Four was outdated, outclassed and out-performed. The 650’s 60 hp made it the slowest four-cylinder 650 on the market, and at 20.3 in. from case cover to case cover, the engine was almost 3 in. wider than the Yamaha 650 Maxim’s. Since Honda hoped to attract both the cruiser-oriented and the performance-minded with the Nighthawk, the legendary 650 engine turned out to be, well, less than legendary in its newest incarnation.

Honda’s engineers realized they couldn’t get both the power and the narrow profile the Nighthawk demanded by simply patching and tinkering with the old engine again. So, it was the end of that line, successor time. Goodbye past, hello present.

The 1983 Nighthawk 650 sports a brand new engine: rubber-mounted dohc, four valves per cylinder, maintenance-free hydraulic valve lash adjustment, lightweight valve actuating. Short, because the transmission is minus a shaft, and narrow, 16.5 in. from case cover to case cover now, compared with the Maxim’s 17.6 in.

The new engine gives the Nighthawk a claimed 72 bhp at 9500 rpm, and performance figures to prove it. Its 12.13-sec. quarter-mile puts it a league or two ahead of last year's model, which consistently was in the 13s. It now one-ups the Maxim, which trails at 12.91 sec. Have yet to be impressed? Then consider these dragstrip times: Honda CX500 Turbo, 12.64 sec.; Yamaha Turbo Seca 650, 12.68 sec.; Honda CB750F, 12.59 sec.; Suzuki GS750EX, 12.54 sec.; and Yamaha 750 Seca, 12.52 sec. The Nighthawk 650 outruns them all. It even rivals Kawasaki’s GPz750, which runs the quarter in 1 1.93 sec.

You Remember the Honda CB650? Well, Forget It. You Already Have? Okay, Now Look At the Nighthawk 650.

Not bad at all for a shafty outfitted more for the homecoming dance than the homecoming game.

There were additional refinements. Not only is the Nighthawk narrower this year, it’s shorter and lighter. Overall length is 84.3 in., wheelbase is 57.5 in., and weight is 465 lb. Contrast that to the old Nighthawk, with a length of 87 in., a 59-in. wheelbase, and a weight about 20 lb. higher.

The frame is double-cradle tubular steel, with air-assisted 39mm telescopic forks on a leading axle, brake-activated anti-dive damping on one fork. An adjuster sets anti-dive to one of four positions. Flex is combated by an integral fork brace. In back, the two Showa shocks have five-way adjustable spring pre-load and four-way adjustable rebound damping.

Front wheel braking is provided by dual piston calipers and 10.9-in. discs. Rear wheel braking is by a rod-operated single leading shoe drum. Braking is very good; 31 ft. from 30 mph and 119 ft. from 60 mph.

The square headlight throws a wide 55/60-watt beam. Instrumentation includes the standard stuff: speedometer, electric tachometer, odometer, resettable trip odometer, neutral indicator, oil pressure light, turn and high beam indicators, and taillight warning light. There also are LCDs (liquid crystal displays) showing fuel supply and gear position. The fuel gauge display is a horizontal bar graph; when it gets down to one bar, indicating less than a gallon of fuel remaining, the lone bar blinks as a warning. The gear display reads in numerals through the first five gears, with OD designating sixth, or as Honda calls it, overdrive. The instruments are arranged on a rectangular console against a dark background and a green graph-paperish grid.

Under good conditions, the Nighthawk has a range of about 200 mi. on its 3.5 gal. gas tank. Mileage on the test loop worked out to 56mpg. Most of the 650s tested have run between 50 and 60 mpg, putting the Honda on the high side of average.

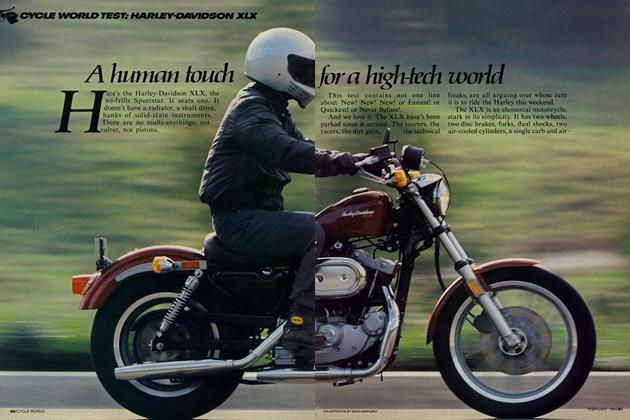

The appearance . . . well, they say one picture is worth quite a few words. In this case, it’s true. Take a look. Honda describes the rectangular headlight and instrument panel as “high tech.’’ The handlebars rise up and roll forward. The seat has a distinct step in it, even if it doesn’t park the passenger high up on the queen's throne. The mufflers are sliced diagonally in what is generally referred to as a “baloney cut.” The fuel tank starts out big at the front, but tapers to a comet’s tail in the rear. What is not black (engine) or chrome (pipes, shocks, handrails and a few other odds and ends), is a very, very dark shade of blue. You can’t tell it from the color pictures, but it’s something of a stormy-midnight-in-themountains-when-it’s-about-to-hail blue. The five-spoked cast wheels have dark highlights. There you have it: the Nighthawk look.

Back to the big news: Honda’s new-era engine.

Most of the Nighthawk 650’s newfound torquey power comes from the new cylinder head. A narrow included angle between the four valves in each cylinder yields a compact pentroof combustion chamber that enables quick burn times. The valves, smaller because there are more of them, are lighter than those in an eight-valve head, so they can be opened faster without courting float and disaster. Also, they have more flow at low lifts, where what is important isn’t valve area, but the cylindrical area provided by valve lift multiplied by valve circumference. The old engine had 31.5 mm intake valves, so with a 2mm valve lift, intake flow area was 198 sq. mm. The 1983 engine has 23-mm. intake valves, two per cylinder, so the same 2mm. lift generates an intake flow area of 289 sq. mm, or 46 percent more. And the new motor reaches this lift quicker because of the faster acceleration the smaller valves can withstand.

The high accelerations are assisted by more than small valves. The actuating system includes a hydraulic lash adjusting system that keeps reciprocating weight low and permits steeper cam ramps. The cams actuate the valves through finger type followers, similar to those used in Suzuki’s four-valve engines except that each valve has its own follower instead of sharing a forked follower. The Nighthawk 650’s followers pivot on small hydraulic adjusters that take up any clearance while the cam is on the base circle. When the opening ramp presses down on the follower, the adjuster locks solid, permitting almost no movement. This isn’t exactly new technology; as far as we can tell, this type of lash adjustment system was used first on the Pontiac sohc Six, and more recently has seen use on Mercedes and Porsche car engines.

Still, it’s an imaginative application, and has been tailored by Honda’s engineers to the needs of a motorcycle engine. The only weakness the system has is oil aeration. We use the word weakness with reluctance, because you also could consider it a safeguard. At high rpm, air bubbles become trapped in the oil, making it springier and allowing the adjuster to pump down and move. To prevent this, the Nighthawk 650 engine provides small reservoirs in the oil passages through the cylinder head, spaces where excess air can bleed off. But at sustained speeds above the engine’s 10,000 rpm redline, the reservoirs become inadequate, the adjusters pump down, clearance develops and a persistent clattering starts up. That means it’s time to stop abusing the engine. A built-in, non-destructive warning.

The valve timing in the Nighthawk engine is an illustration of how successful the large valve-area, fast-opening approach can be. The intake valves open at 10° BTDC, and close at 35° ATDC. The exhaust train has the same 7.5mm lift and 225° duration, opening at 40° BTDC, and closing at 5° ATDC. This provides only 15° of overlap between intake and exhaust, timing more appropriate for a lawnmower engine than a 11 Ohp/liter motorcycle engine. So, the 650 obviously doesn’t rely on long durations and overlap, but uses the large valve flow area and rapid opening to breathe. Consequently, while power is strongest at the top of the rpm range, 8000 10,000 rpm, to be exact, it’s good everywhere from idle up.

Okay. Now that Honda found the power they wanted, they had to pack it more compactly than it had been. To do this, they borrowed the philosophy behind the Yamaha Maxim, and refined it. The alternator was moved behind the cylinders, over the transmission, spinning on its own shaft. The shaft is driven by a silent chain coming from a sprocket on the crankshaft, next to the centrally located cam chain. The centrifugal advance was deleted from the ignition system, so the pickups could be moved in closer; this way, the component wouldn’t take up valuable space. In place of a mechanical advance system, an all-electronic advance was adopted. In addition, the starter was moved a bit. Before, it occupied the space now taken up by the alternator. For 1983, it was shoved back; through a gear reduction link.

Power is transmitted from the crankshaft in the same manner as it is in Yamaha’s 650. A large gear was carved from one of the crankshaft webs, and it directly drives the clutch gear. The intermediate jackshaft used in the 500 Four series was dropped.

For the smallest possible engine package, Honda abandoned the nicety of a horizontally split line on the engine cases, with the crank and transmission shaft centerlines falling on it. Instead, the split now angles down from the engine front to rear, with only the crank and mainshaft centerline on the split. Now, the countershaft is above and to the rear of the mainshaft, supported entirely in the top engine case.

The right angle gearset that takes off for the shaft drive fits on the right side of the countershaft; on the Yamaha version, an additional shaft is used. But with this direct approach, Honda’s engine not only is narrower than the Maxim’s, but inches shorter as well. And, because engine power is transmitted through fewer shafts and gearsets, less power is lost in the transmission. To permit this direct drive, the engine rotates in the opposite direction of the wheels, or “backwards.”

Next up in the News Dept, is the minimal maintenance required by the Nighthawk 650. Shaft drive; no chain to adjust. Hydraulic clutch; no cable to adjust. Electronic ignition; no messing with points. Automatic cam chain tensioner; again, no chain to adjust. Automatic valve lash adjusters; no valve-setting. Brushless alternator, fan-cooled, overdriven and with a second set of windings; longer life, increased output. Even an electric tach; no drive cable to lube. And an oil cooler, permitting less frequent oil changes. About the only thing left for a rider to do is replace the plugs, check the battery level, check the tire pressure and wipe the Nighthawk down every now and then.

All of these workings get Honda’s new 12-month, unlimited mileage warranty.

That’s what the Nighthawk 650 has. How’s it work? Pretty damn well. Lever the choke up with your left thumb, and it starts right up; no cold nature here. A couple of blocks away, you can back it off. As we’ve noted, there’s plenty of nice, torquey power, from idle on up. The transmission has a clunky sound and feel, and first-to-second will balk unless the shift lever is firmly booted up. The clutch is grabby, especially after a hard, fast start. Roll-on acceleration is very peppy in the first five gears. Pick-up is a little slow in sixth, but keep in mind that top gear is set up for high fuel mileage cruising. If you toe it down once to fifth, pretty much the equivalent of top in other 650s with a five-speed transmission, you’ll leave the crowd far behind.

The Nighthawk 650 exhibits very little of the rise and dips usually associated with shaft-driven bikes. Honda says that’s because the shorter engine allows room for a longer swing arm and drive shaft, minimizing torque-inspired shaft effects on the suspension when the throttle is rolled on or off. But our resident expert maintains that the lack of shaftcaused ups and downs is due to something else: a harder-than-usual suspension. The Nighthawk’s swing arm, he notes, is no longer than those on a number of other shaft-drive bikes which do exhibit rear-end changes on acceleration or deceleration. So, the effects are being held down by the suspension, he maintains.

It’s a credible theory. The Nighthawk ride is on the choppy side, with stiff spring and damper rates in the rear. The stiff suspension is most noticeable riding at freeway speeds over a ripply pavement. The bike shakes and rattles, as well as rolls.

Cornering clearance is exceptional, and surprising considering that the Nighthawk has half a boulevard cruiser’s soul. Other than the pegs, everything that might drag is tucked away, and it’s possible to use up all of the tread on the tubeless Dunlops ( 1 00/90-19-in. in front, 130/90-16-in. in back) and then some. Steering is responsive, and steering effort is light at speeds under 60 mph. Over 60, effort is increased and steering slows, but it’s still sporty enough. Oddly enough, the excellent handling is due in part to the stepped cruiser seat; the rider, and thus the center of gravity, is low on the bike.

It’s possible to gain even more clearance by pumping up the front forks (6 psi is the maximum recommended pressure;

0 psi is recommended for most riding conditions) and dialing up the adjustments for spring pre-load and rebound damping on the shocks. But if you thought the ride was choppy before . . .

The anti-dive system on the left fork does what it’s supposed to. There’s little sign that steering is affected by having anti-dive on one fork and not the other, but one of our riders maintains he was able to feel some fork flex when braking hard and cornering radically. Honda says it’s not possible. He says it is. In any event, the system works well under normal conditions. As do the brakes: strong, reliable, with a nice, reassuring feel at the controls.

On the road, comfort is good, even considering the stiff ride. The seat is well-padded and the rider’s part is long enough to permit some fore-aft adjustment of riding position. Vibration from the engine almost is non-existent; chalk that up to the rubber mounts and shaft drive. Even the bars and pegs are free of > buzz. Engine chatter is—well, it just doesn’t. The loudest noise is a whirring from the gear primary.

Odds and ends. The oil level is easy to check, but hard to top up unless you have a funnel with a looong neck. The hinged, locking gas cap opens up and to the rear, but not far enough; there’s not much working room for the pump nozzle. The sidestand is located so that it’s somewhat awkward to get down. On the plus side, removing the rear wheel took five minutes and a minimum of tools. Never before, said the rider who pulled it, has a Honda given up its rear wheel that easily.

On the whole, we liked it. A lot. The only things we found to quarrel with had to do with style. And, we realize that the old saws are all true: beauty is in the eye of the beholder, etc. Style is relative. You ought to see the way some of us dress.

But we’ll run through our objections, anyway, for the record. Too much plastic. Or polycarbonate or whatever they’re calling that tacky stuff now. On the Nighthawk, most of it is disguised, chromed to look like something more than a petroleum by-product. It’s there in the fork valve stem covers, a silly-looking mudflap that extends below the front fender, a handlebar cover and a couple of little pieces that hide a gaggle of oil lines and the like from public scrutiny. In a bizarre switch, one thing that isn’t plastic is made to look like it. It’s the hydraulic junction for the front brake lines, where the single line from the master cylinder branches to feed the two sets of calipers. During the 1970s, Honda stylists began shielding these junctions with plastic covers, usually with the Honda name molded in. On the Nighthawk, the cast aluminum junction is designed to look like a plastic cover. Strange times, these.

Anyway. Most of us took exception to the cruiser styling; we’d’ve preferred sportier dress for what is a sporting machine. If we had our way, we’d change the seat (something flat), the fuel tank (less peanut-styled), the instrument cluster (no graph lines, please), the headlight (round) and the handlebars (lower, maybe a tad more rear-set). But first, we'd switch mufflers.

Still, it’s worth noting that none of us were all that strident about our gripes. As one editor says: “I’m easily influenced. When something runs well, the other things just don’t seem important.”

Check. What’s important here is this. None of the other 650s are this small and this light. None make this kind of power. In the quarter-mile, the Nighthawk is about a second quicker than the average 650 Four—quite a big difference. It has the acceleration of the average 750. Or better.

And to get all this, the Nighthawk sacrifices almost nothing. SI

HONDA

CB650SC NIGHTHAWK

SPECIFICATIONS

List price $2798

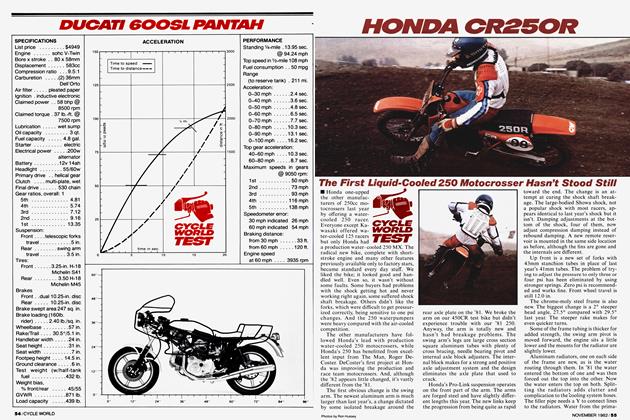

ACCELERATION

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue