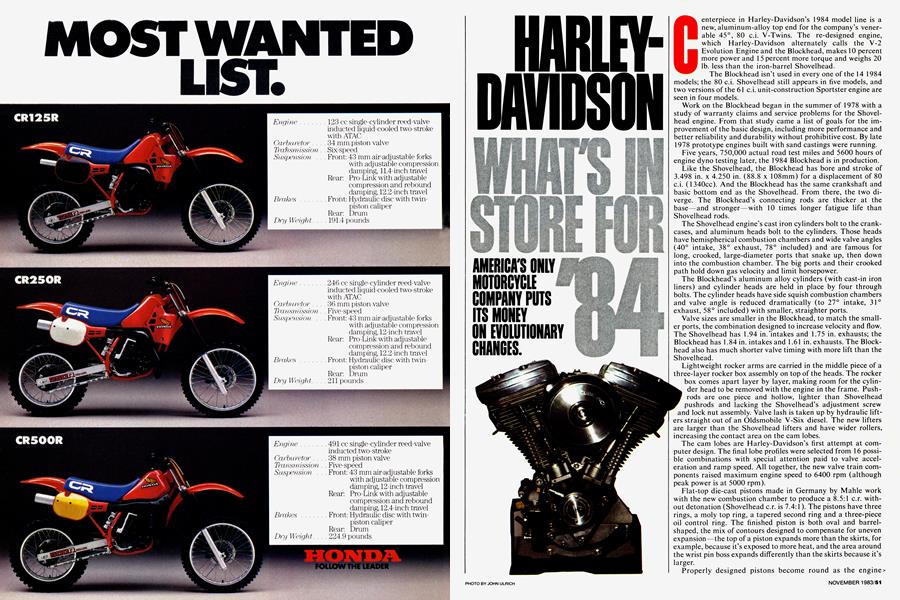

HARLEY-DAVIDSON

WHAT'S IN STORE FOR '84

AMERICA'S ONLY MOTORCYCLE COMPANY PUTS ITS MONEY ON EVOLUTIONARY CHANGES.

Centerpiece in Harley-Davidson’s 1984 model line is a new, aluminum-alloy top end for the company’s venerable 45°, 80 c.i. V-Twins. The re-designed engine, which Harley-Davidson alternately calls the V-2 Evolution Engine and the Blockhead, makes 10 percent more power and 15 percent more torque and weighs 20 lb. less than the iron-barrel Shovelhead.

The Blockhead isn’t used in every one of the 14 1984 models; the 80 c.i. Shovelhead still appears in five models, and two versions of the 61 c.i. unit-construction Sportster engine are seen in four models.

Work on the Blockhead began in the summer of 1978 with a study of warranty claims and service problems for the Shovelhead engine. From that study came a list of goals for the improvement of the basic design, including more performance and better reliability and durability without prohibitive cost. By late 1978 prototype engines built with sand castings were running.

Five years, 750,000 actual road test miles and 5600 hours of engine dyno testing later, the 1984 Blockhead is in production.

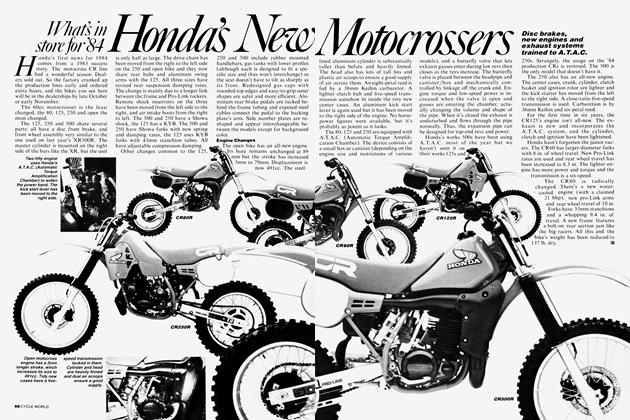

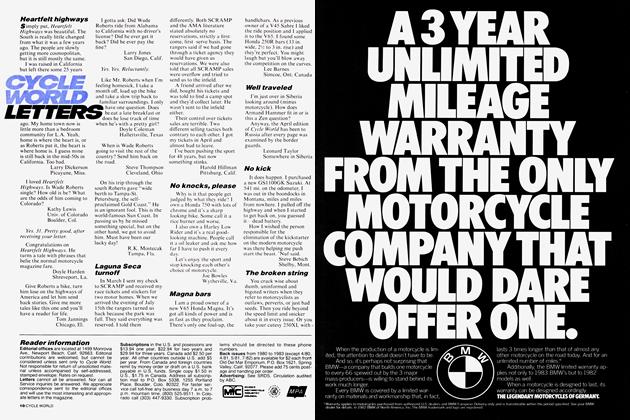

Like the Shovelhead, the Blockhead has bore and stroke of 3.498 in. x 4.250 in. (88.8 x 108mm) for a displacement of 80 c.i. (1340cc). And the Blockhead has the same crankshaft and basic bottom end as the Shovelhead. From there, the two diverge. The Blockhead’s connecting rods are thicker at the base—and stronger—with 10 times longer fatigue life than Shovelhead rods.

The Shovelhead engine’s cast iron cylinders bolt to the crankcases, and aluminum heads bolt to the cylinders. Those heads have hemispherical combustion chambers and wide valve angles (40° intake, 38° exhaust, 78° included) and are famous for long, crooked, large-diameter ports that snake up, then down into the combustion chamber. The big ports and their crooked path hold down gas velocity and limit horsepower.

The Blockhead’s aluminum alloy cylinders (with cast-in iron liners) and cylinder heads are held in place by four through bolts. The cylinder heads have side squish combustion chambers and valve angle is reduced dramatically (to 27° intake, 31° exhaust, 58° included) with smaller, straighter ports.

Valve sizes are smaller in the Blockhead, to match the smaller ports, the combination designed to increase velocity and flow. The Shovelhead has 1.94 in.’intakes and 1.75 in. exhausts; the Blockhead has 1.84 in. intakes and 1.61 in. exhausts. The Blockhead also has much shorter valve timing with more lift than the Shovelhead.

Lightweight rocker arms are carried in the middle piece of a three-layer rocker box assembly on top of the heads. The rocker box comes apart layer by layer, making room for the cylinder head to be removed with the engine in the frame. Pushrods are one piece and hollow, lighter than Shovelhead pushrods and lacking the Shovelhead’s adjustment screw and lock nut assembly. Valve lash is taken up by hydraulic lifters straight out of an Oldsmobile V-Six diesel. The new lifters are larger than the Shovelhead lifters and have wider rollers, increasing the contact area on the cam lobes.

The cam lobes are Harley-Davidson’s first attempt at computer design. The final lobe profiles were selected from 16 possible combinations with special attention paid to valve acceleration and ramp speed. All together, the new valve train components raised maximum engine speed to 6400 rpm (although peak power is at 5000 rpm).

Flat-top die-cast pistons made in Germany by Mahle work with the new combustion chamber to produce a 8.5:1 c.r. without detonation (Shovelhead c.r. is 7.4:1 ). The pistons have three rings, a moly top ring, a tapered second ring and a three-piece oil control ring. The finished piston is both oval and barrelhaped, the mix of contours designed to compensate for uneven expansion—the top of a piston expands more than the skirts, for example, because it’s exposed to more heat, and the area around the wrist pin boss expands differently than the skirts because it’s larger.

Properly designed pistons become round as the engine reaches operating temperature, minimizing piston slap and allowing closer running tolerances. None of this is revolutionary, but it’s new to Harley-Davidson.

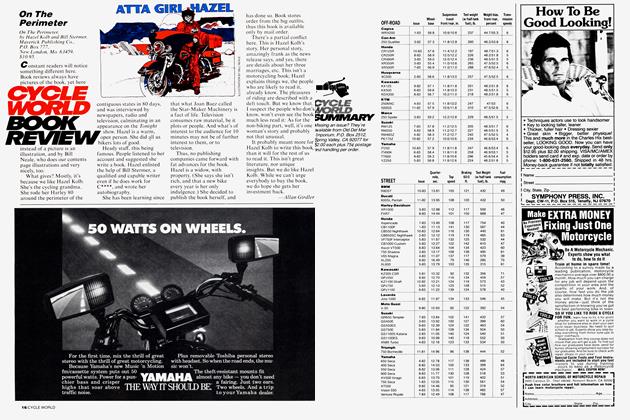

SHOVELHEAD

BLOCKHEAD

The new pistons are each 4 grams lighter than Shovelhead pistons. And because expansion rates are carefully figured into the design, Blockhead pistons don’t need the steel struts used underneath the domes—running perpendicular to the wrist pin—in Shovelhead pistons.

For years Shovelheads consumed lots of oil, mostly because oil was pumped to the valve gear faster than it could drain back into the sump: excess oil pooled around the valve guides and was sucked into the intake port when the valve opened. Modifications to the Shovelhead improved the situation a few years ago, and the Blockhead design goes a step further. Oil drains from the cylinder head down all four head/cylinder bolt bores, the pushrod tubes and the tappet blocks.

The blockhead uses a bolt-on, rubber intake manifold and a 38mm Keihin single-throat carburetor.

Compression screens replace copper washers in the exhaust ports, the screens plugging with carbon to form a seal between each head and its exhaust pipe. Two bolts secure each head pipe to its head.

The electronic ignition system has a new two-stage advance curve; under light load and at small throttle openings, ignition advance is 50° BTDC. When vacuum drops in the intake manifold, advance backs off to 32° BTDC. Lots of advance improves fuel economy but brings with it detonation under heavy loads; the new Harley-Davidson ignition delivers the benefit of more advance without the disadvantage of detonation.

There’s a new compensator (primary drive) sprocket on the Blockhead, using fewer, but heavier, springs than the Shovelhead’s sprocket. All the 1984 Blockhead models have chain primary drive. The transmissions (one four-speed, one five-speed) linked to the Blockhead are identical to the transmissions used with the Shovelhead.

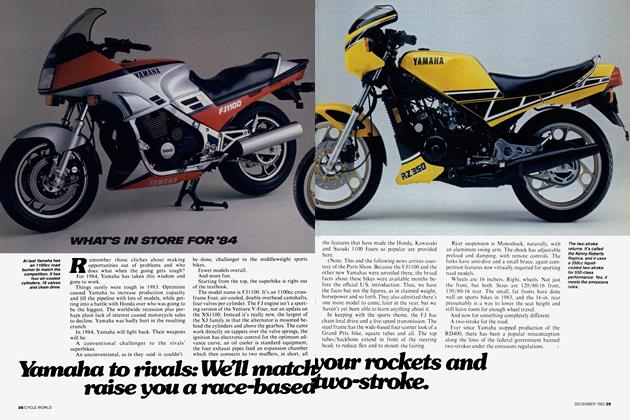

Four 1984 models combine the new engine with a five-speed transmission and the rubber engine mount system debuted in 1980: the FLTC Tour Glide and FLHTC Electra Glide dressers, the FXRT Sport Glide tourer, and the FXRS Low Glide cruiser. A fifth model using the Blockhead engine is the new FXST Softail, a cruiser with rigid engine mounts and a fourspeed transmission. The FXST is styled to look like it has a rigid tailsection. The triangulated swing arm is linked to dual gascharged expansion shock absorbers hidden horizontally under the transmission. The suspension layout was designed and built by independent engineer Bill Davis. The design caught the eye of Harley-Davidson chairman Vaughn Beals at a rally, and Harley-Davidson bought the rights to the patented system.

Besides its rear suspension system, the FXST’s claim to recognition is the longest wheelbase of any mass-produced motorcycle, 66.3 in.

The Shovelhead engine with rigid engine mounts and a fourspeed transmission is used in the FLH Electra Glide and FLH Special Edition Electra Glide dressers and the FXE Super Glide, FXWG Wide Glide and FXSB Low Rider cruisers. The Super Glide claims a 26-in. seat height. The Low Rider has belt primary and final drives, and the Wide Glide comes with a chain primary drive and belt final drive.

The XLS Roadster, XLH Sportster and XLX61 all use the 61 c.i. (lOOOcc) unit-construction, iron-barrel, iron-head Sportster engine with chain primary and final drives and various stages of styling. The XR 1000 has a high-performance version of that engine, with a new iron barrel and aluminum alloy cylinder head, plus dual carburetors and high-performance exhaust system. The XR1000 is also the only 61 c.i. Harley-Davidson with dual front disc brakes. The XLs are given only one of the 11.5 in. discs, but by juggling the leverage ratio, the single disc system requires 30 percent less lever effort than the small dual discs it replaces. The XR 1000 is available in Harley-Davidson racing colors orange and black as well as the standard charcoal gray.

All the evolution in the world is no good without a commitment to quality. During a recent press trip to Harley-Davidson's test facility in Talledega, Alabama and to an assembly plant in York, Pennsylvania, that commitment was evident. Everybody from tough-talking Beals to Union president Eric Burkey to workers on the plant floor talked about quality, and the testing program indicated the words weren’t for show only. In one test, a FXRT and a FL.TC with Blockhead engines were flung around the Talledega Speedway tri-oval at an average speed (including pit stops) of 85 mph for 8000 mi. Both came through with flying colors; no mechanical problems and a respectable 1 500 mil. per quart of oil, wide open.

“We’re stressing test rides for 1984,” Beals told the press, “because people can’t believe the difference in modern HarleyDavidsons. We know that quarter-mile and high speed isn’t our game, and we don’t want the four valves (per cylinder) and four curbs and $200 tune-up that comes with that type of performance. We want something a shade-tree mechanic can take care of, with no arcade stuff. A needle that goes around and tells you where you are is fine for us. Function is where it’s at, not knick-knacks, and we’re after all-around motorcycles. We strive for balance.”

Speaking of balance, just prior to the press and dealer show, Harley’s research people gave a selected (and limited) audience a look at the current version of the long rumored V-Four. H-D brass have hinted, there have been some sneak photos of disguised prototypes on test, but this was the first time outsiders if that’s the word for dealershave seen the project in the metal.

Delicacy is required here. Like BMW, who later this year will show the American press their new Four that won’t be on sale in the U.S. until 1985, Harley must remind the public that they, too, make changes and introduce new engines, while at the same time too much fuss over engines you can’t buy would reduce the appeal of engines you can buy.

Harley has a V-Four, and the V-Four will be produced. What nobody knows or will say, is when.

Meanwhile, the evolved V-2 will be used in five of the company’s 14 new models, quality and employee morale are up, and Harley-Davidson is ready. g]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

November 1983 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

November 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Book Review

November 1983 By Allan Girdler -

Departments

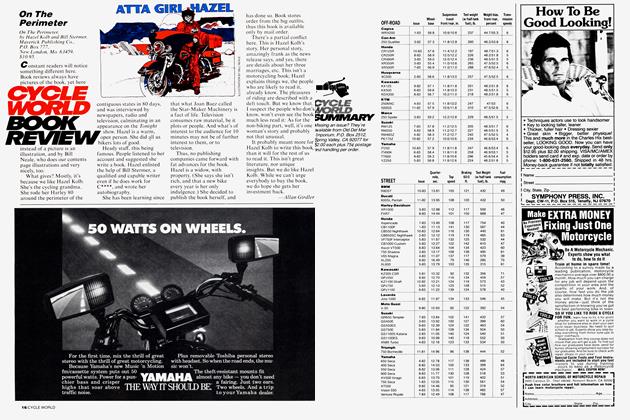

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

November 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

November 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

November 1983