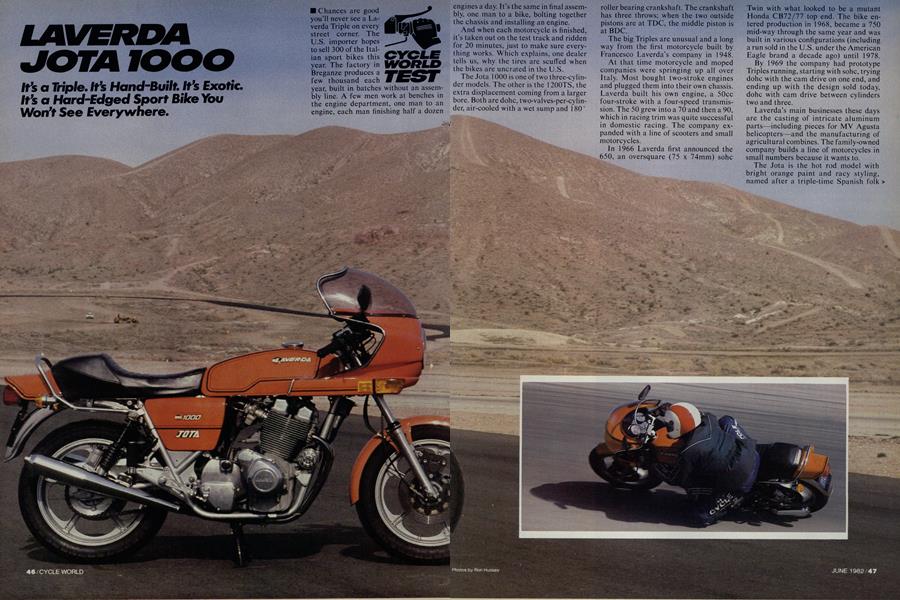

LAVERDA JOTA 1000

CYCLE WORLD TEST

It's a Triple.It's Hand-Built. It's Exotic. It’s a Hard-Edged Sport Bike You Won’t See Everywhere.

Chances are good you’ll never see a Laverda Triple on every street corner. The U.S. importer hopes to sell 300 of the Italian sport bikes this year. The factory in Breganze produces a few thousand each year, built in batches without an assembly line. A few men work at benches in the engine department, one man to an engine, each man finishing half a dozen engines a day. It’s the same in final assembly, one man to a bike, bolting together the chassis and installing an engine.

And when each motorcycle is finished, it’s taken out on the test track and ridden for 20 minutes, just to make sure everything works. Which explains, one dealer tells us, why the tires are scuffed when the bikes are uncrated in the U.S.

The Jota 1000 is one of two three-cylinder models. The other is the 1200TS, the extra displacement coming from a larger bore. Both are dohc, two-valves-per-cylinder, air-cooled with a wet sump and 180° roller bearing crankshaft. The crankshaft has three throws; when the two outside pistons are at TDC, the middle piston is at BDC.

The big Triples are unusual and a long way from the first motorcycle built by Francesco Laverda’s company in 1948.

At that time motorcycle and moped companies were springing up all over Italy. Most bought two-stroke engines and plugged them into their own chassis. Laverda built his own engine, a 50cc four-stroke with a four-speed transmission. The 50 grew into a 70 and then a 90, which in racing trim was quite successful in domestic racing. The company expanded with a line of scooters and small motorcycles.

In 1966 Laverda first announced the 650, an oversquare (75 x 74mm) sohc

Twin with what looked to be a mutant Honda CB72/77 top end. The bike entered production in 1968, became a 750 mid-way through the same year and was built in various configurations (including a run sold in the U.S. under the American Eagle brand a decade ago) until 1978.

By 1969 the company had prototype Triples running, starting with sohc, trying dohc with the cam drive on one end, and ending up with the design sold today, dohc with cam drive between cylinders two and three.

Laverda’s main businesses these days are the casting of intricate aluminum parts—including pieces for MV Agusta helicopters—and the manufacturing of agricultural combines. The family-owned company builds a line of motorcycles in small numbers because it wants to.

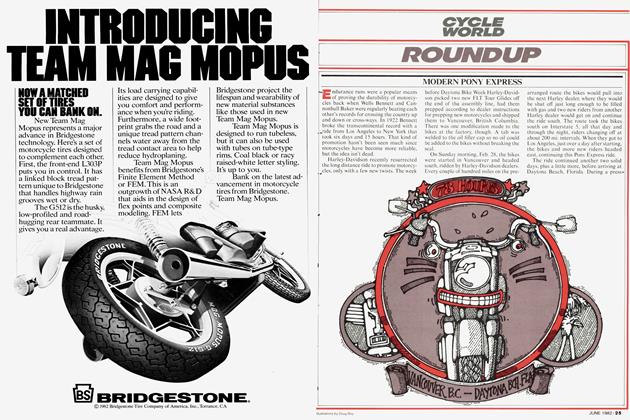

The Jota is the hot rod model with bright orange paint and racy styling, named after a triple-time Spanish folk dance and fitted with frame-mounted half fairing, clip-on handlebars and rearset footpegs.

The Jota Triple has the same 75 x 74mm bore and stroke as the first Laverda 650 Twin and displaces 980.7cc. (The 1200 TS has an 80mm bore for 1116cc). The combustion chambers are hemispherical, each with one 39.5mm intake and one 36.4mm exhaust valve and the spark plug offset to one side. Intake valve angle is 20.7° from vertical, exhaust valve angle 19.8°. Cast threering pistons have moderate domes and c.r. is 9.3:1.

The valves are operated by cams acting directly on bucket-style tappets. Valve clearance is adjusted by replacing winkler-cap shims which fit over the end of the valve stems, underneath the valve buckets. Adjusting valve clearance requires removal of the camshafts. With valve timing measured from 0.01 5 in. lift, intake valves are opened 50° BTDC and closed 74° ABDC; exhaust valves are opened 70° BBDC and closed 38° ATDC. Intake lift is 10mm, exhaust lift is 9.5mm.

The cams run in bearing blocks held in place by studs on top of the head casting. Each cam has three bearings. The outside bearing blocks are one piece and fit over the camshaft ends. The middle bearing block is split and fits together around the cam, next to the cam chain sprocket. The cam bearing blocks are pressure fed. A hole in one side of each block sprays oil onto the adjacent cam lobe.

The roller cam chain runs off a crankshaft sprocket located between cylinders two and three. The chain is split and held together by a master link, and must be fed through separate tunnels in the cases, cylinder block and cylinder head.

The cases are split horizontally and the crankshaft has four main bearings. The mains are pressure-fed, but the big end bearings depend upon oil splash for lubrication. The crank pins are 36mm and are pressed into flywheel holes that have been induction hardened. In the induction hardening process, an electric current is used to heat up a ring of metal around each press-fit hole. The ring of hardened metal resists flexing and cracking encountered, for example, in TZ750 flywheels.

From the crankshaft back, the Laverda is unusual in several ways, First, primary drive is a triplex roller chain to the multiplate wet clutch. Second, the outside edge of each friction plate engages the clutch basket with myriad sawteeth instead of the more conventional flat, wide dogs fitting into a slotted basket. Third, the clutch hub and final drive sprocket both ride on the transmission mainshaft. Fifth gear and the engine sprocket fit over the mainshaft as a unit and usually spin independently of the mainshaft. In first through fourth gears, power travels from the mainshaft to the countershaft through one of four gearsets, and a locked-in-place countershaft gear delivers power to the fifth gear/engine sprocket unit. When the bike is shifted into fifth gear, a sliding selector ring splined to the mainshaft engages dogs on fifth gear, and power is routed along the locked-together mainshaft directly from the clutch to the engine sprocket.

Each of the three 32mm, round-slide DeirOrto carburetors has an accelerator pump. The carbs are mounted at a downward angle and linked together with a bellcrank. A single cable runs to the throttle grip. Short rubber tubes run from the carburetors into a plenum box, but there isn’t any air filter. (The 1200 model does have a filter).

Chokes are controlled by a lever mounted on the left handlebar.

The chromed exhaust has thick-walled. head pipes joined into a collector pipe which then splits into two mufflers, making a 3-into-l-into-2 system. The upswept mufflers bend in the middle, the forward section running under the swing arm to the collector, the rearward section pointing straight back. Exhaust gasses exit through a chromed stub of pipe protruding from a short reverse cone welded to the body of each muffler.

The Bosch inductive ignition system is electronically controlled and magnetically triggered. Pickups are mounted on the left side of the crankshaft, under the primary cover. Cylinders One and Three share a dual-lead coil, and Cylinder Two has its own single-lead coil. Ignition pickups are mounted 180 ° apart to match the Triple’s uneven firing order as well as triggering a waste spark during the exhaust stroke.

Pistons One and Three, remember, rise and fall together, with piston Two 180° apart—when One and Three are at TDC, Two is at BDC. Starting with Cylinder One firing, the crank turns 180 ° and Cylinder Two fires. Another 180° and Cylinder Three fires. The next cylinder to fire is One again, but not until 360° after Three, followed 180° later by Two. So there’s a full crankshaft revolution of dead space, so to speak.

The 360° of dead space would be split into neat 1 80° parts by a fourth cylinder firing, if the Triple had a fourth cylinder. Which is why the Triple feels and sounds, at certain rpm, like a Four with one cylinder dead.

Other Threes avoid uneven firing by staggering the crank throws 120°, giving two-strokes three firings per crankshaft revolution and four-strokes two firings per revolution. Laverda engineers say that early experiments with a 120° crankshaft increased objectionable highfrequency vibration. It’s interesting to note, however, that Laverda Triples with 120 cranks have been shown in Europe and are likely to reach the U.S. in 1983 or 1984.

In many ways the Laverda Triple is ahead of its time. Despite its late ’60s design, it has features now being touted as new and innovative on many Japanese bikes, features like narrow valve angles and standard aluminum oil cooler.

But the Laverda shows the age of its design in some ways. There isn’t an oil filter, rather a metal screen. And, yes, the valve angle is narrow, but because the cams operate the valves directly through bucket-style tappets, the engine is tall, 20 in. from the sump (and the center of the lower frame tube) to the top of the cam cover. The angle and height of the carburetors brings engine unit height up to 22 in. Most dohc Japanese Fours measure between 17 and 19 in. The Honda V-Four engine is 17 in. tall from frame rail to cam cover, the Yamaha XV920 19 in. from cam cover to exhaust pipe centerline, which is where the bottom frame tube would be if the XV had one.

The Laverda engine would be taller still except that the designers tilted the cylinders forward about 16° from vertical.

So the Laverda has a big, tall frame to carry its tall engine. There’s one large diameter backbone and two main cradle tubes running from the steering head under the engine, behind the swing arm pivot and up to the tail section.

Triangulated bracing runs between the backbone and the cradle tubes behind the steering head. Other tubes are welded to the rear of the backbone and run down to intersect the cradle tubes above the swing arm pivot. The swing arm pivot itself is mounted in plates welded between the rear downtubes and the main cradle tubes. The upper shock mounts are fastened to the cradle tubes just below the tail section tubes.

The tall engine and frame give the Laverda a seat height of 33 in., very high for a road bike. But if the frame is tall, it isn’t long. The Laverda engine is 17 in. long at the cases and 20.5 in. long from tip of cylinder head to rear of cases, and the swing arm pivot is close behind the engine cases. Coupled with 28° of rake (trail is 4.3 in.), the wheelbase is 57.5 in., about normal for a short Japanese 750.

Bolted to the frame are all sorts of interesting parts. The swing arm rides in needle roller bearings, the steering head in tapered rollers. The forks are Marzocchi, the brakes Brembo with drilled cast iron front discs and a solid cast iron rear disc. Shocks are also Marzocchi, with piggyback reservoirs. Wheels are aluminum alloy, cast by the Laverda factory and featuring a patented safety rim designed in conjunction with Dunlop to hold the tire in place in case of puncture. (Laverda isn’t completely out of the patent/trademark race given so much store by Japanese firms—besides the rims, the name “Jota” is trademarked).

There are parts on this motorcycle that make it easy to believe that Laverda does a big business in aluminum castings. The rearset foot controls, for example, have cast levers (and machined alloy pegs) mounted on beautiful, flawless cast plates bolted to the frame. (Engine and wheel castings are likewise works of art).

Other bits and pieces ensure that no one will mistake the Laverda rider for a cruiser. The headlight is mounted out on a stalk from the steering head, positioned to match up with the frame-mounted half fairing. Front turn signals are integrated into the fairing. Handlebars mount to the upper triple clamp but zig-zag down and back to duplicate the position and angle of clip-ons. Although the bike has passenger pegs, the shape of the seat means any passenger will be—or will become— an intimate friend. The taillight is mounted under a swept-back tail section painted—like the tank, fairing, side covers and front fender—a brilliant orange.

The seating position makes riding the Laverda excellent training for Formula One racing, one staffer observed, not what the British describe as “sit up and beg.”

The instruments and handlebar switch pods are made by Nippondenso (as is the alternator). The tach is mounted on the left, the speedometer on the right. Our test bike, like other Laverda Triples we’ve seen, came with 150-mph speedometer, a little bit of anarchy in the midst of NHTSA 85-mph speedometer mandates. Neutral and charge lights are mounted in the face of the tachometer, high beam and headlight flash lights in the speedometer face. (The headlight switch on the left bar has a spring-loaded position to flash the high beam before passing, a European feature).

The feel of the Laverda is unique as its appearance. There is no doubt that this is a sport bike, built for racing along the

Autostrada or Autobahn or deserted secondary highway at extra-legal speeds. It’s geared tall, turning about 3500 rpm at 60 mph, with a calculated 139 mph top speed in fifth gear at the 8000 rpm redline.

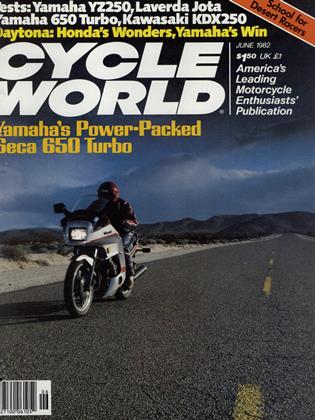

Despite the lumpy idle and missingcylinder feeling at low rpm, the Laverda makes good power. It’s willing to chug around town at 3000 rpm and below, then changes personality dramatically as rpm approaches 6000. From there on up the bike explodes forward. At the dragstrip a good launch kept the rpm between 6500 and 8000 and shot the Laverda through the quarter mile in 1 1.97 sec. with a terminal speed of 112.78 mph. While the Laverda is capable of running 11s, the trick is to avoid bogging, which can be difficult since the hydraulic clutch lacks the feel-at-friction-point of cable-operated clutches. Most passes were in the 1 2.20 sec. range.

There is no trick to the Laverda’s top speed of 134 mph in the half mile. It’s that fast, thanks to its fairing and the low rider profile produced by the low bars and rearset pegs. The top speed compares well with the Kawasaki GPz 1 100’s 136 mph and the Suzuki GSllOOE’s 135 mph. The Suzuki Katana is a faster 1000, however, reaching 140 mph.

Good lap times at the local road race circuit also demand lots of rpm. Accelerate off a corner with the tach reading 4500 rpm and the Laverda lingers, slowly gaining speed. Keep the tach needle near the readline and the bike charges out of turns. On tighter courses, or on twisty canyon roads, the Laverda doesn’t rush up to redline in fifth gear the way a Suzuki GS 1 100 or Kawasaki 1 100 or Katana does. It just doesn’t have the same kind of straightaway-eating, excellentdrive-producing torque the Fours do. The Laverda needs a long straight to reach top rpm in top gear.

What the Laverda does have is superior cornering clearance and excellent stability. The suspension is stiff, good for cornering clearance, but not so stiff that bumps set the bike to wobbling the way a Katana does on rough sweeping turns. Some of the credit there goes to the rigid frame. The Laverda is the most stable lOOOcc motorcycle we’ve ridden at Willow Springs, and has the best cornering clearance.

It’s also the hardest 1000 to ride fast. Vibration produced by the Triple at highway speeds is low intensity and subdued. Near redline it’s so bad it’s hard to hold onto the bars and work the conrols. Our test bike came equipped with non-standard, vibration-absorbing foam grips and still was awful at speed. Short bursts on the street or at the drags are one thing; lap-after-lap on the racetrack or mileafter-mile on a country road are something else.

Adding to the problems are control levers located too far from the bars for riders without large hands. The reach from grip to lever is big enough and awkward enough to cost time in transitions for average-sized riders. Rolling off the gas, downshifting and grabbing the front brakes takes longer, for example, when the rider's hand can’t easily span the distance between grip and lever with enough slack left over to blip the throttle between shifts.

The shift lever throw is too long. Riders without size 1 1 feet often missed upshifts despite moving the lever far enough to shift a Japanese bike through 1 Vi gears. Some riders found that pulling the left foot up completely off the peg helped when upshifting, but that doesn’t solve the problem with handlebar lever spacing. The Laverda, as sold, requires big hands and feet to ride quickly around a road course.

Adding to problems with the front brake lever is the engagement point of the brakes. Full stop is reached with the lever far from the grip, and a little lever travel produces lots of braking. The bike stopped well enough, taking 32 ft. to stop from 30 mph and 133 ft. from 60 mpfi, so there’s no trouble with actual power.

The height of the engine and the engine configuration itself makes the Laverda top heavy. This is no lightweight, weighing 546 lb. with half a tank of gas, and the combination of weight, weight placement and low bars makes the Laverda ungainly in the parking lot and at low speeds. There isn’t a side stand. Dismounting, poking your foot around underneath the exhaust to find the centerstand, and getting the bike up on that stand is more difficult than it should be, especially on slight slopes.

At most speeds the low bars/top weight clumsiness disappears, but it shows up again at high speed, particularly in fast S-curves. Like the Katana, the Laverda requires a lot of effort to make the transition from left to right.The huge 4.00-18 Pirelli Gordon fitted to the front of our test bike didn’t make the steering any more nimble.

What the Laverda needs is a set of dogleg control levers, and a revised shift linkage, perhaps a change in linkage ratios to reduce lever travel. We tried a set of Luftmeister vibration-reducing handlebar inserts (made of steel tubes and star-shaped rubber washers) and found the inserts reduced vibration through the bars both at normal highway cruising speeds and maximum rpm.

The control changes would make the bike easier to ride and wouldn’t alter the image of an exotic hot-rod. The same kind of detailing no doubt prompted the use of Japanese instruments and switch pods.

The lights are excellent, the horn loud. The mirrors, mounted on stalks on the outside of the fairing, show mostly rider sleeve and elbow and don’t give a good view directly behind, but they look racey. At certain speeds the combination of engine vibration and road speed (corresponding to 80 mph in fifth) the mirrors folded back completely. Installing the Luftmeister vibration dampers raised the fold-back speed to over 100 even though the mirrors aren’t bar mounted.

In the Laverda we have a genuine exotic sports bike, a rarity produced in limited numbers. Because the bike is handbuilt, it is expensive, suggested retail being $5950. It is fast. It is unusual. The firing order and crank layout gives it a four-minus-one feel at low rpm, but that feeling disappears around 3500 rpm. Vibration near redline is intense, diminishing to strong power pulses at cruising speeds of 60-70 mph. The suspension (and ride) is stiff, the seating (crouching?) position uncomfortable at slow speeds, the exhaust note distincitve.

This motorcycle is not made in huge numbers and doesn’t sacrifice performance or form for middle-of-the-road appeal.

It is what it is. Interested Laverda owners know that; accept what the bike can and cannot do; and want what it offers. Who can argue with that?

LAVERDA JOTA 1000

$5950