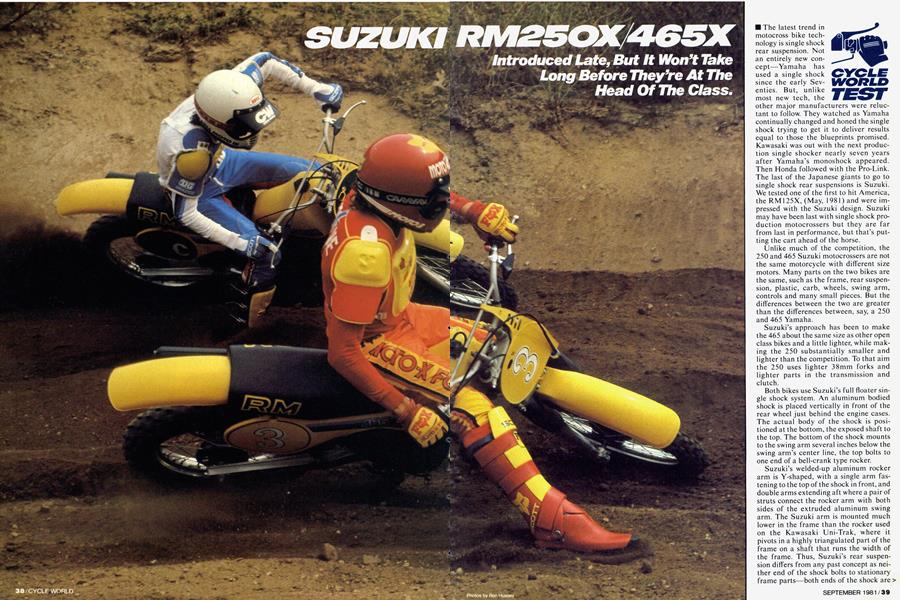

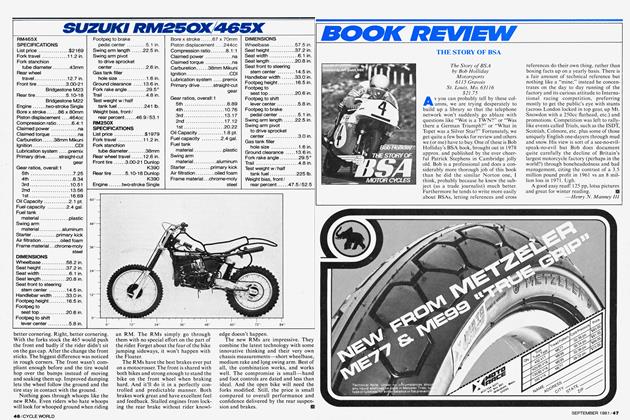

SUZUKI RM250X/465X

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Introduced Late, But It Won’t Take Long Before They’re At The Head Of The Class.

The latest trend in motocross bike technology is single shock rear suspension. Not an entirely new concept—Yamaha has used a single shock since the early Seventies. But, unlike most new tech, the other major manufacturers were reluctant to follow. They watched as Yamaha continually changed and honed the single shock trying to get it to deliver results equal to those the blueprints promised. Kawasaki was out with the next production single shocker nearly seven years after Yamaha’s monoshock appeared. Then Honda followed with the Pro-Link. The last of the Japanese giants to go to single shock rear suspensions is Suzuki. We tested one of the first to hit America, the RM125X, (May, 1981) and were impressed with the Suzuki design. Suzuki may have been last with single shock production motocrossers but they are far from last in performance, but that’s putting the cart ahead of the horse.

Unlike much of the competition, the 250 and 465 Suzuki motocrossers are not the same motorcycle with different size motors. Many parts on the two bikes are the same, such as the frame, rear suspension, plastic, carb, wheels, swing arm, controls and many small pieces. But the differences between the two are greater than the differences between, say, a 250 and 465 Yamaha.

Suzuki’s approach has been to make the 465 about the same size as other open class bikes and a little lighter, while making the 250 substantially smaller and lighter than the competition. To that aim the 250 uses lighter 38mm forks and lighter parts in the transmission and clutch.

Both bikes use Suzuki’s full floater single shock system. An aluminum bodied shock is placed vertically in front of the rear wheel just behind the engine cases. The actual body of the shock is positioned at the bottom, the exposed shaft to the top. The bottom of the shock mounts to the swing arm several inches below the swing arm’s center line, the top bolts to one end of a bell-crank type rocker.

Suzuki’s welded-up aluminum rocker arm is Y-shaped, with a single arm fastening to the top of the shock in front, and double arms extending aft where a pair of struts connect the rocker arm with both sides of the extruded aluminum swing arm. The Suzuki arm is mounted much lower in the frame than the rocker used on the Kawasaki Uni-Trak, where it pivots in a highly triangulated part of the frame on a shaft that runs the width of the frame. Thus, Suzuki’s rear suspension differs from any past concept as neither end of the shock bolts to stationary frame parts—both ends of the shock are> mounted to moving parts and the shock can be compressed from either end.

Much attention has been directed at placing the weight of the suspension low and keeping the parts of it light. The low placement of the bottom of the shock moves the center of gravity down considerably and almost all of the components are made of light weight materials. The swing arm is an aluminum extrusion, the top rocker is aluminum, the shock body is aluminum, the remote reservoir is aluminum. The shock spring, top-out bumper bracket and rear struts are the only steel parts.

The shock is adjustable and rebuildable. Spring preload is set by turning a ring at the bottom of the shock body. Suzuki has a special tool available for the job and it would probably be a wise purchase. Of course you could use a long drift punch, but you take the chance of destroying the threads on the aluminum shock body. Rebound damping is adjusted by turning a ring at the top of the shock. Four positions are provided marked 1,11,111,1111. Stock setting is II and it worked best for most tracks. Changing the adjustment isn’t simple. It’s necessary to remove the right side number plate to reach the knob. We just left it off while we were dialing-in the rear. The excellent owner’s manual tells how to change oil and do other necessary maintenance on the shock and rear suspension components. Disassembly is required when it’s time to grease the moving parts but Suzuki doesn’t state any time intervals. All moving parts have quality bearings and good grease seals so lubrication schedules shouldn’t be excessive.

A totally new frame is used for the Floater. It has a large single front downtube and backbone. The backbone is heavily gusseted and a smaller tube strengthens the backbone by forming a triangle. The shock rocker sits in the bottom of a frame triangle just below the seat and short straight pieces tie the whole thing together. All frame tubing is chrome-moly steel. Steering head bearings are a combination of tapered rollers and ball. The caged rollers are placed at the bottom of the steering head; the area that takes the major impact; the balls are placed at the top; an area of less impact. The tapered rollers provide the required load strength where it’s needed, while the ball bearings at the top are lighter and offer less resistance to turning forces.

Steering head angle is set at 29.5° on both bikes. That’s almost a desert racing spec when compared with the 28 ° rake of most modern dirt racers. But rake doesn’t tell it all. The RMs are shorter than most other racers. The center section of the bike is short because of modern engine designs that are short and compact. Even with a 22.5 in. swing arm, the RMs only have 57.5 and 58 in. wheelbases. The short wheelbases didn’t require steep rakes for quickness. Additionally, the rear of the bikes have 1.5 in. more travel than the front raising the rear of the RMs a little higher than the front, which also promotes quicker turns.

The difference in fork stanchion tube sizes didn’t make much sense until the bikes were weighed. The 250 weighs 16 lb. less than the open bike. Suzuki has bravely gone a different route from everyone else—the 250 uses a combination of 465 and 125 parts. Most 250 motocrossers are just open bikes with smaller engines. The RM250 doesn’t fit that form. Where the heavier part wasn’t needed, it wasn’t used. Since 250s don’t have as much horsepower to push the front end around, the engineers used the smaller 38mm tubes from the RM 125. The forks on both bikes have air valves. The 465 doesn’t need them as the forks are already too stiff. The front of the 250 feels too soft in the garage but proved about right for most riders on the track. The air valves offer adjustment for those who want it. Both bikes have strong aluminum triple clamps that incorporate rubber handlebar pedestals. The difference in wheelbase between the 250 and 465 is the result of the larger fork tubes. The larger tube diameter moves the axle farther forward on the open bike.

Suzuki gets the award for the best hubs ever put on a motocross bike. Both hubs are new designs with spokes that exit the hub with very slight bend. Suzuki’s design isn’t a perfect straightpull design but it’s close. In fact it’s close enough that we didn’t have to tighten any of the spokes during our long race testing of the two machines. Both hubs have innovative brake placement with the brake drum positioned toward the center of the hubs so braking force is spread more evenly to both sides of the wheel. Don’t be disappointed because of the lack of a dual leading shoe at the front of the RMs. They don’t need it. The front hub measures nearly 6 in. compared with 5.1 for the YZ and around 5.5 for Honda’s CR. Add a brake arm that’s 4 in. long and you have a strong and progressive brake.

Rear hubs are different on the 250 and 465, despite an owners manual that says they are the same. But then the owners manual says the 465 should be warmed up 5 min. because of the water cooling. The 250 uses the 125’s smaller drum, while the 465 uses a 5.1 in. drum. Both are operated by exposed cables and have full-floating backing plates. Other brake parts are a strange mixture of primitive and highly refined. The static arms are beautiful aluminum pieces, while the brake pedals are crude-looking steel parts that wrap under the footpegs instead of over them. By running the pedals under the pegs the pedals won’t catch some of the plastic boots. Both bikes have easily removed rear wheel assemblies. It’s not necessary to remove or touch the axle adjusters while removing the wheel—just unscrew the axle nut and remove the axle. Both adjusters stay put on the swing arm. And since the adjusters stay put, there’s no need to readjust the chain after messing with the wheel. Too bad everyone doesn’t have such a simple and effective system.

Both bikes have motors that are almost all-new. And both have had the reed cage moved from the lower part of the cylinder where it dumped gas directly into the crank cavity, to a position between the carburetor and the piston. The reed block is a huge design that uses eight plastic petals. Additionally, the reed cavity has large balance ports leading to the rear transfer ports and a rectangular port at the bottom of the intake tract feeds gas directly to the crank. One of the bonuses of Suzuki’s older design was long piston life because the design allowed a fulllength piston skirt. The new design still has a long piston skirt and reed area has been increased almost three times!

Internally both bikes are different from each other and from last year’s RMs. Both have new cranks, new rods, new transmission gears (although the ratios are the same), and new clutch arm locations. The clutch lever has been moved from the top of the clutch cover to the left rear of the engine’s cases. About the only parts unchanged are the clutch plates. The 250 still has six fiber plates, the 465 uses eight of them and that should end the clutch failures of past open bikes.

Suzuki still doesn’t use a radial cylinder head. No real complaint here, as some people prefer them, others don’t, and the radial heads are heavier.

Cylinder porting is revised, both engines having a similar design but the heights and widths of the ports are different to fit each bike’s size. A bridged intake port sits low in the cylinder, the exhaust port is large and unbridged. Four transfer ports, two on each side of the cylinder, look normal enough until the rears split and make two boost ports just above the intake. The cylinder really is full of holes.

Like Suzuki’s smaller RM 125, the 250 and 465 have double air cleaner systems. It looks like the same part as the smaller bike but is slightly different. Around the air intake the 125 has a rather restrictive water baffle, the larger bikes don’t. Otherwise, there’s not much difference. The massive airbox is formed around the shock, nicely mounted in rubber pads and uses a dual foam filter on each side of the machine. Filters are cut from flat foam stock and don’t have any glued or sewn seams. Each inner filter mount is a plastic grid with pins at the cross junctions and the outer hold-down is formed like the inner, so the filters are held firmly and can’t move around. Filter surface area is greater than other airboxes. A protective cover fits over each filter and the air inlets are placed so water can’t easily enter. If water does enter, each side cover is fitted with a good one-way drain. Both side number plates are shaped so they also help keep water from the airbox. Water shielding use is among the best around.

As impressive as the airbox unit is, it isn’t without problems. Rumors had it the airbox was restrictive and performance gains could be had by simply opening the top of the airbox cover so more air could enter. Of course wet weather use suffers if the top of the cover is opened but it was summer and rainy weather was a long way off. We carefully cut part of the top away and the rumors are right, there does seem to be a performance advantage. Cleaning the filters is a minor hassle that requires removal of the side number plate (four flat-head screws that have loose spacers behind them) then removal of two phillips head screws in each cover, then one phillips head in each outer grid. The screw head selection is a little strange. Not much reason to mix them up. The flat-head screws are trick however. They look and feel like they’re titanium! But the seat bolts and many other larger bolts are normal steel. Four small side number screws aren’t going to save much weight. Anyway, once apart don’t follow the manual’s instructions for replacement. It doesn’t mention greasing the edges of the filter box. If grease isn’t used, and lots of it. dirt will leak around the edges of the filters. It happened on both our test machines. Then it’s a real job trying to clean the inside of the massive box with all of its grids preventing easy access. We resorted to removing the air hose from the carburetor and squirting the inside of the box with a plastic squeeze bottle filled with cleaning fluid. Prevent all the extra work and ruined engine by heavily greasing all of the edges where the filters seat.

Most exterior plastic pieces on the RMs are shared. Fenders are much like previous RM parts. Some like them, some don’t. They are a little thin and mud tends to bend them under. Tanks are a fresh design styled after the factory racers. They’re narrow and have a low rear so it’s easy to slide far forward and weight the front wheel. Capacity is 2.4 gal. and the vent hose is equipped with one of Suzuki’s slick plastic vent tubes that attaches to the handlebar cross bar. You won’t need an instruction manual to figure out the petcock either—down is on, sideways is off.

Seats are shared on the larger RMs and are slightly different than last year’s. The base is made from plastic and the front tongue that slips under a frame rail is also plastic and molded into the base. Foam hardness is correct and the wider seat is comfortable for long rides. The seat covers are cheap and thin. They rip at the front around the seat/tank junction and easily tear if the bike is crashed. And who doesn’t crash?

Both bikes have a small, low feeling to them. And it’s not a false feeling. Seat heights are a reasonable 37.2 in., nearly an inch lower than most modern motocross bikes. The works-like tank with its low top adds to the small feel. Kick starters are the same on both bikes. The boot contact area has raised steel ribs preventing slippage when wet or muddy and the unit folds completely out of the way when not in use. The length of the lever has been kept intentionally short so you don’t have to try and raise your leg above your head to start the bikes. But unless you turn your toe out slightly before kicking, the footpeg will rap you in the top of the instep. Most of our testers thought it a reasonable tradeoff.

Mikuni carburetors are equipped with a pull type choke that has a large plastic knob on its top. Although it’s placed under the pipe, it’s not difficult to reach or use. One to four kicks are required to start both bikes when cold. It mainly depends on who is doing the kicking. A good healthy kick is required, especially on the open machine. Doesn’t matter how long the bikes are warmed-up, they still blubber and burp until they have been wound out a few times.

Both bikes needed jetting changes. The 250 was the worst. We had to drop the needle one notch, lower the pilot jet from a 50 to a 35 and change the main jet to a 220. Some early machines also had a too-rich needle jet in them—ours had already been changed. If you have difficulty jetting a 250 take a look at the needle jet. It should be an R8 not an R9. The open bike proved easier to jet. Changing the pilot to a 60 and cutting the back of the slide 1mm got rid of most of its low-end richness.

Once jetted properly both bikes pinged off the low-end when ridden hard. Suzuki said not to worry it would be okay. At that point timing checks seemed in order. Suzuki doesn’t give normal timing settings in the manual, Timing is simply a matter of aligning two marks. Forget about using a dial indicator, you can’t. The center rotor isn’t marked, only the outside edge of the backing plate. The manual shows the recommended procedure. Remove the cover, take out the front backing plate screw and loosen the other one slightly. The alignment marks are under the front screw. We turned the backing plate counter clockwise and retarded the timing on both machines. It becomes strictly a guess since a dial indicator can’t be used. We moved the mark on the backing plate down until it pointed at the lower edge of the small cast-in boss below the case alignment arrow, about 1mm. Crude yes, but it worked! Pinging disappeared and power proved better on both bikes. The timing marks that come on the bikes must have been derived with 110 octane gasoline. With today’s poor quality gas, retarding the timing is beneficial. And with everything right the bike stopped fouling so many plugs. The open bike wasn’t bothered but the 250 was plagued with plug fouling until it was dialed right.

With the engines running well the bikes became much more enjoyable to ride. Rear suspension action is beyond criticism. The Floater suspension is as close to perfect as any suspension ever made. Bumps, holes, lips, jumps, dropoffs, uphills, downhills and any other kind of situation is simply soaked up without bothering the rider. The rider never gets shocked or kicked around. Now that all the Japanese companies have introduced single shock rear suspensions the Suzuki’s has proved to be the best. The only possible criticism is the small size of the remote reservoir. There might be a handful of pros capable of getting it hot enough to fade. For any other riders, it’s not a problem.

Proponents of the single shock systems claim the single shocks do a better job of keeping the rear wheel on the ground in acceleration. The Suzuki Floater certainly appears to do so. Watching the Suzuki in a race it’s possible to see a Suzuki rider gain one or two bike lengths coming out of a bumpy corner against the competition. The rear wheel doesn’t spin uncontrollably and the bike doesn’t try to get sideways, enabling the rider to use more throttle. The end result is a hole shot.

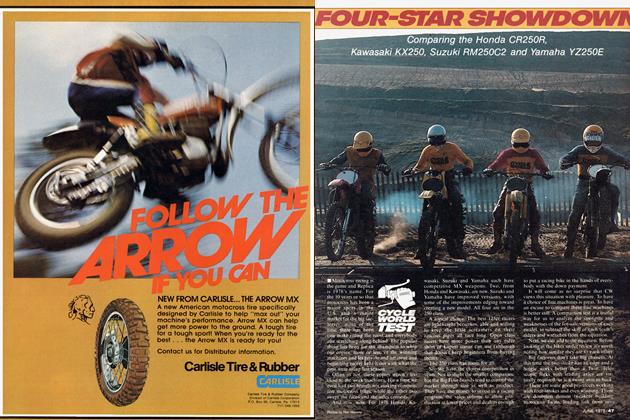

While the 250 Suzuki can get a hole shot because of the suspension a Honda CR250R or Yamaha YZ250H could beat the Suzuki if a race track has a long starting area because they have more top-end power.

Except for the neat horsepower across a broad rpm range, the RM250X feels like a 125.It’s light, weighing in at 225 lb. with a half tank of premix. That’s 20 lb. lighter than a Honda CR250R and 8 lb. lighter than a Yamaha YZ250H. The little RM is easy to pitch around and the relatively short wheelbase lets it turn quickly. Shifting is smooth and precise although it is necessary to back the throttle off slightly when upshifting. No one missed any shifts or doubted the transmission in any way. Ratios are correct for most racing uses. The final gearing will fit most tracks but there’s plenty of room for larger sprockets as well as smaller ones.

Corners demand a far forward seating position and the bike is shaped to accommodate that position. The tank is low at the rear and short, the seat long. Cornering style doesn’t matter, the bike likes them all. Balance is perfect and the bike doesn’t exhibit any foul traits or nasty habits for the rider to adjust too. The front suspension that felt a little too soft in the garage is almost perfect for a fast pro on a MX course. Travel could be more as it’s a little short at 11.2 in. Thus it gives away up to an inch of travel to some of its competitors. But the 12.7 in. of rear wheel travel almost makes up for it as long as the really bad stuff is attacked on the back wheel! Steering precision is good but not as good as a YZ250H or Maico Mega. The small diameter forks flex when smashing into the far sides of big whoops and when the track gets chopped up toward the end of the day. It’s not enough to slow the rider or make a difference in winning or not winning, just enough that you know it’s happening.

The open machine also feels light and small, although the difference isn’t as much as with the 250’s comparative weights. Power is plentiful and everywhere. With the stock jetting and timing specs, the bike has a definite tendency towards violence in the first part of the powerband, much like last year’s YZ465G. It starts off a little blubbery and rich then explodes with an eye blurring rush of acceleration. Rejetting and retiming turns the power into a smooth controllable rush that doesn’t flatten out on top like most open engines. Most open motocrossers allow a little thinking time after 5th gear is shifted into—the RM just keeps accelerating like it was still in a lower gear. Starts are easy in 2nd or 3rd, depending on the traction at hand. The transmission in the 465 would hang up in 3rd under hard acceleration until it had some racing miles. Then the problem disappeared.

Large diameter 43mm KYB forks are standard on the 465. Travel is the same as the 250’s at 11.2 in. But the big forks don’t work as well as those on the 250. The first couple of inches are okay then the forks get too stiff. The ride across rippled ground is rough and the front of the bike bobs around like a cork on the ocean. Big bumps are handled well, the problem is caused mainly by small irregularities. Slowing across rippled ground causes lots of head shaking and the bike becomes a handful to control. Too bad such beautiful units are valved wrong. We spent two days trying to adjust them. Oil weights from 2Vi through 10 at every practical level was tried. The harshness remained. Next came Yamaha YZ250H springs. No difference. Then we tore the forks apart and checked the fit of all moving parts. No binding or bent parts were found. New oil seals were installed just in case the original ones were defective and causing too much drag. The oil weight juggle was repeated. No dice, they were still rough.

Finally we sent the fork dampers to suspension specialist Gil Valencourt, owner of Works Performance Shock Co. Gil welded up a couple of compression holes, drilled new compression holes higher on the rod and drilled a couple of additional rebound damping holes. The forks were reassembled and 5 weight KalGuard oil filled to 6 in. from the top of the bottomed stanchions. The difference was amazing. The front is smooth and cushy and no shock is transmitted to the rider. But best of all, the head shake is gone. The shaking was the result of the forks not moving when the front wheel encountered bumps. The force was turning the front tire back and forth. The mod only costs $15. Send the bare damper rods to Works Performance, 8730 Shirley Ave. Northridge, Calif. 91324. It’ll turn the RM465 into an outstanding machine.

A side benefit from the fork change is> better cornering. Right, better cornering. With the forks stock the 465 would push the front end badly if the rider didn’t sit on the gas cap. After the change the front sticks. The biggest difference was noticed in rough corners. The front wasn’t compliant enough before and the tire would hop over the bumps instead of moving and soaking them up. Improved damping lets the wheel follow the ground and the tire stay in contact with the ground.

SUZUKI RM250X/465X

$2169

Nothing goes through whoops like the new RMs. Even riders who hate whoops will look for whooped ground when riding an RM. The RMs simply go through them with no special effort on the part of the rider. Forget about the fear of the bike jumping sideways, it won’t happen with the Floater.

The RMs have the best brakes ever put on a motocrosser. The front is shared with both bikes and strong enough to stand the bike on the front wheel when braking hard. And it’ll do it in a perfectly controlled and predictable manner. Both brakes work great and have excellent feel and feedback. Stalled engines from locking the rear brake without rider knowledge doesn’t happen.

The new RMs are impressive. They combine the latest technology with some innovative thinking and their very own chassis measurements—short wheelbase, medium rake and long swing arm. Best of all, the combination works, and works well. The compromise is small—hand and foot controls are dated and less than ideal. And the open bike will need the forks modified. Still, the price is small compared to overall performance and confidence delivered by the rear suspension and brakes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue