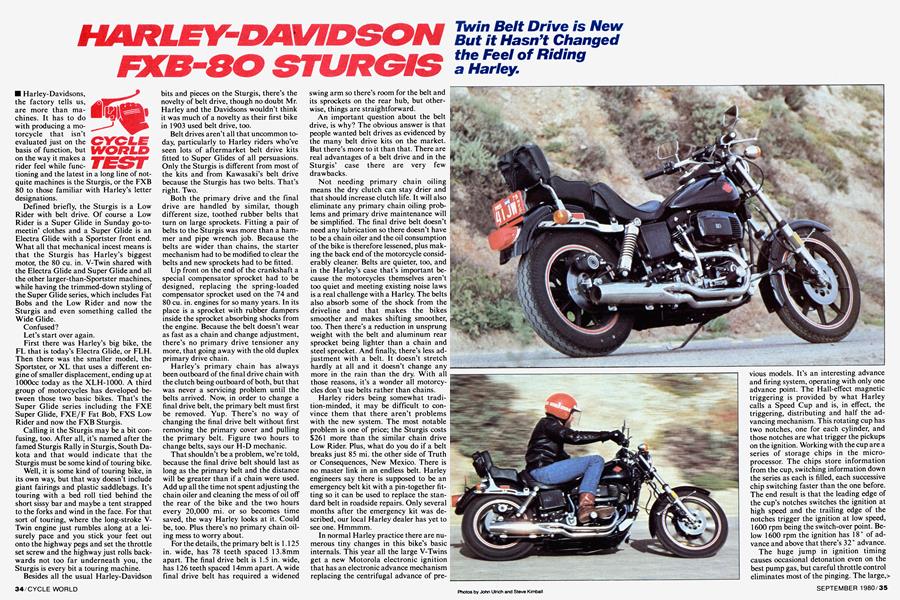

HARLEY-DAVIDSON FX-80 STURGIS

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Harley-Davidsons, the factory tells us, are more than machines. It has to do with producing a motorcycle that isn't evaluated just on the basis of function, but on the way it makes a rider feel while functioning and the latest in a long line of not-quite machines is the Sturgis, or the FXB 80 to those familiar with Harley's letter designations.

Defined briefly, the Sturgis is a Low Rider with belt drive. Of course a Low Rider is a Super Glide in Sunday go-tomeetin’ clothes and a Super Glide is an Electra Glide with a Sportster front end. What all that mechanical incest means is that the Sturgis has Harley’s biggest motor, the 80 cu. in. V-Twin shared with the Electra Glide and Super Glide and all the other larger-than-Sportster machines, while having the trimmed-down styling of the Super Glide series, which includes Fat Bobs and the Low Rider and now the Sturgis and even something called the Wide Glide.

Confused?

Let’s start over again.

First there was Harley’s big bike, the FL that is today’s Electra Glide, or FLH. Then there was the smaller model, the Sportster, or XL that uses a different engine of smaller displacement, ending up at lOOOcc today as the XLH-1000. A third group of motorcycles has developed between those two basic bikes. That’s the Super Glide series including the FXE Super Glide, FXE/F Fat Bob, FXS Low Rider and now the FXB Sturgis.

Calling it the Sturgis may be a bit confusing, too. After all, it’s named after the famed Sturgis Rally in Sturgis, South Dakota and that would indicate that the Sturgis must be some kind of touring bike.

Well, it is some kind of touring bike, in its own way, but that way doesn’t include giant fairings and plastic saddlebags. It’s touring with a bed roll tied behind the short sissy bar and maybe a tent strapped to the forks and wind in the face. For that sort of touring, where the long-stroke VTwin engine just rumbles along at a leisurely pace and you stick your feet out onto the highway pegs and set the throttle set screw and the highway just rolls backwards not too far underneath you, the Sturgis is every bit a touring machine.

Besides all the usual Harley-Davidson

bits and pieces on the Sturgis, there’s the novelty of belt drive, though no doubt Mr. Harley and the Davidsons wouldn’t think it was much of a novelty as their first bike in 1903 used belt drive, too.

Belt drives aren’t all that uncommon today, particularly to Harley riders who’ve seen lots of aftermarket belt drive kits fitted to Super Glides of all persuasions. Only the Sturgis is different from most of the kits and from Kawasaki’s belt drive because the Sturgis has two belts. That’s right. Two.

Both the primary drive and the final drive are handled by similar, though different size, toothed rubber belts that turn on large sprockets. Fitting a pair of belts to the Sturgis was more than a hammer and pipe wrench job. Because the belts are wider than chains, the starter mechanism had to be modified to clear the belts and new sprockets had to be fitted.

Up front on the end of the crankshaft a special compensator sprocket had to be designed, replacing the spring-loaded compensator sprocket used on the 74 and 80 cu. in. engines for so many years. In its place is a sprocket with rubber dampers inside the sprocket absorbing shocks from the engine. Because the belt doesn’t wear as fast as a chain and change adjustment, there’s no primary drive tensioner any more, that going away with the old duplex primary drive chain.

Harley’s primary chain has always been outboard of the final drive chain with the clutch being outboard of both, but that was never a servicing problem until the belts arrived. Now, in order to change a final drive belt, the primary belt must first be removed. Yup. There’s no way of changing the final drive belt without first removing the primary cover and pulling the primary belt. Figure two hours to change belts, says our H-D mechanic.

That shouldn’t be a problem, we’re told, because the final drive belt should last as long as the primary belt and the distance will be greater than if a chain were used. Add up all the time not spent adjusting the chain oiler and cleaning the mess of oil off the rear of the bike and the two hours every 20,000 mi. or so becomes time saved, the way Harley looks at it. Could be, too. Plus there’s no primary chain oiling mess to worry about.

For the details, the primary belt is 1.125 in. wide, has 78 teeth spaced 13.8mm apart. The final drive belt is 1.5 in. wide, has 126 teeth spaced 14mm apart. A wide final drive belt has required a widened

swing arm so there’s room for the belt and its sprockets on the rear hub, but otherwise, things are straightforward.

An important question about the belt drive, is why? The obvious answer is that people wanted belt drives as evidenced by the many belt drive kits on the market. But there’s more to it than that. There are real advantages of a belt drive and in the Sturgis’ case there are very few drawbacks.

Not needing primary chain oiling means the dry clutch can stay drier and that should increase clutch life. It will also eliminate any primary chain oiling problems and primary drive maintenance will be simplified. The final drive belt doesn’t need any lubrication so there doesn’t have to be a chain oiler and the oil consumption of the bike is therefore lessened, plus making the back end of the motorcycle considerably cleaner. Belts are quieter, too, and in the Harley’s case that’s important because the motorcycles themselves aren’t too quiet and meeting existing noise laws is a real challenge with a Harley. The belts also absorb some of the shock from the driveline and that makes the bikes smoother and makes shifting smoother, too. Then there’s a reduction in unsprung weight with the belt and aluminum rear sprocket being lighter than a chain and steel sprocket. And finally, there’s less adjustment with a belt. It doesn’t stretch hardly at all and it doesn’t change any more in the rain than the dry. With all those reasons, it’s a wonder all motorcycles don’t use belts rather than chains.

Harley riders being somewhat tradition-minded, it may be difficult to convince them that there aren’t problems with the new system. The most notable problem is one of price; the Sturgis costs $261 more than the similar chain drive Low Rider. Plus, what do you do if a belt breaks just 85 mi. the other side of Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. There is no master link in an endless belt. Harley engineers say there is supposed to be an emergency belt kit with a pin-together fitting so it can be used to replace the standard belt in roadside repairs. Only several months after the emergency kit was described, our local Harley dealer has yet to see one. Hmmmm.

In normal Harley practice there are numerous tiny changes in this bike’s basic internals. This year all the large V-Twins get a new Motorola electronic ignition that has an electronic advance mechanism replacing the centrifugal advance of previous models. It’s an interesting advance and firing system, operating with only one advance point. The Hall-effect magnetic triggering is provided by what Harley calls a Speed Cup and is, in effect, the triggering, distributing and half the advancing mechanism. This rotating cup has two notches, one for each cylinder, and those notches are what trigger the pickups on the ignition. Working with the cup are a series of storage chips in the microprocessor. The chips store information from the cup, switching information down the series as each is filled, each successive chip switching faster than the one before. The end result is that the leading edge of the cup’s notches switches the ignition at high speed and the trailing edge of the notches trigger the ignition at low speed, 1600 rpm being the switch-over point. Below 1600 rpm the ignition has 18° of advance and above that there’s 32° advance.

Twin Belt Drive is New But it Hasn't Changed the Feel of Riding a Harley.

The huge jump in ignition timing causes occasional detonation even on the best pump gas, but careful throttle control eliminates most of the pinging. The large,> 3.498 in. bore is responsible for the pinging, Harley engineers say, because the large bore means it takes a long time for the flame to spread through the combustion chamber. The lengthy burning time makes an early spark necessary and even the low 8:1 compression ratio can’t eliminate the need for premium fuel. A long 4.25 in. stroke keeps the bore size down somewhat, but that, in turn, limits maximum engine speed to 5500 rpm because of the great inertia forces of the huge engine.

Another major change for 1980 is a new transmission case and a new second gear ratio that’s 10 percent higher than the previous model. Overall ratios on the Sturgis are slightly higher than the ratios on any other Harley-Davidsons because of the slightly different final drive ratio of the belt. With a top gear ratio of 3.27:1 for the Sturgis, 3.42:1 for the other Super Glide versions and only 3.36:1 for the five-speed Tour Glide, the Sturgis will run down the highway with the engine hammering along the slowest. And that suits it just fine.

Having about the same torque as an International Harvester Loadstar, the

Sturgis is quite comfortable with the engine spinning 2700 rpm at 60 mph. That is, after all, only about half the maximum engine speed possible on the giant V-Twin.

Such high gearing doesn’t lend itself to dragstrip performance and the Sturgis suffers in this regard because of the gearing. A 14.64 sec. quarter mile time and trap speed of 91.18 mph put the FXB-80 in company with the average Japanese 400cc Twin. Certainly Harley-Davidsons have had years of success drag racing, but the Sturgis is not intended as a dragster. It does manage a respectable 48 mpg in normal riding, a figure that would be good for a motorcycle with an engine half as big as the Sturgis’. But with a combined volume of 3.5 gal. for the two gas tanks on the Sturgis, cruising range is limited.

In stock tune the Sturgis is about as non-competitive a motorcycle as HarleyDavidson or anyone else could produce, it not having the power for any kind of racing or the suspension and handling to encourage that sort of activity.

What the Sturgis substitutes for handling agility is stability. With its 2 in. extended forks, 31.4° steering rake and over 64 in. wheelbase the Sturgis isn’t going

anywhere but straight unless a rider makes an extreme effort at moving the narrow 28 in. handlebars. A first time rider usually swings wide trying to turn the Sturgis until he learns to muscle the machine around corners sharper than the banking at Daytona. Once accustomed to the Harley’s natural inclination to go straight, a rider can make the Sturgis turn reasonably sharply, as long as not too great an angle of lean is called for. At surprisingly gentle angles the Sturgis drags the folding footpegs on either side, followed soon thereafter by the exhaust on the righthand side and the sidestand on the lefthand side. Only when the Harley grounds down it’s not like grounding a sidestand or centerstand on a small Japanese bike. On the Harley there’s a feeling that it’s not the motorcycle that’s going to move, it’s the road underneath. That same stability that keeps the Sturgis going straight keeps it going around corners, too. High speed sweepers are a natural for the Sturgis. It chugs around fast sweepers at the limit of its cornering clearance with no wiggle or wobble, as solid as a gold bar in a Swiss bank.

Should one want to slow the Harley at the end of a fast ride it will require a vicelike grip and lots of room. Sure the Sturgis has triple disc brakes with lots of swept area. But in an effort to assure that Harley riders never find themselves grabbing too much front brake, the Sturgis (and most every other Harley-Davidson) has incredi bly hard brake pucks. Even if the rider has biceps the size of watermelons and can squeeze the brake lever until it cries uncle and hits the grip the Sturgis still won't come close to locking the front tire. At least the rear brake is capable of providing all the stopping the tire can deliver, but it shouldn't have to work alone.

Thankfully other controls on the Sturgis are much easier to operate. The clutch pulls with a moderate amount of effort as long as the rider isn't one of those pencil-necked geeks with the tiny paws, but of course those types don't ride Harleys. The throttle is the easiest turning throttle made and the fat grips make it even easier so that the throttle set screw (nice touch) will hardly ever be needed. Shifting is, well, not easy, but serviceable. Shift as slow as molasses and things barely clunk. Shift as though this were a dragster and awful noises come from the transmis

sion, though the belts may help smooth out the jerks.

Other features of the Sturgis are a mix ture of good and bad. The locking sidestand is a model of simplicity and good design. It extends easily and once down doesn't allow the bike to roll forward off the stand. On the other hand, there's no centerstand, though hoisting a 610 lb. mo torcycle onto a centerstand isn't much fun. Turn signals on the Harley are, as usual for a Harley, operated by pushing a spring loaded button on either side of the ma chine. The signals stay on as long as the buttons are pushed, making an automatic canceller needless, but making turn signal operation difficult should one try downshifting at the same time. Then there's the kickstarter. It takes a certain weight rider to be able to start the Harley by kicking it and that weight goes up dramatically if the engine is cold. Warm, a healthy 150 pounder can start it while a weak 150 pounder only floods the engine. Cold starts are best left to the fat man at the circus or the electric starter.

For its part the engine runs flawlessly. While the craftiest foreign bikes are adding air suction and accelerator pumps

and even fuel injection the Harley man ages to meet the same emission standards by proper carb jetting, its electronic igni tion and nothing else. And the results are wonderful. Pull the choke knob under the seat, hit the starter button and the Harley eventually grinds itself into action, though accompanied by sounds of protest from the starter much of the time. Push the choke half-way in and the Harley can be ridden away instantly. A block down the street the choke can be pushed completely in and there are no rideability problems. No bucking or stalling. No coughs. It doesn't have to idle at 4000 rpm for 10 mm. Nice what mild tuning and honest to-gosh flywheels can do.

What the Sturgis can't do is provide the kind of comfort a more softly sprung mo torcycle can provide. A ride to Sturgis from farther away than, say, Deadwood 2 mi. down the road would be a good test of a rider's toughness. The seat has little pad ding and there's only one riding posture that fits the combination of low 27 in. seat, short drag-style bars and footpegs. Thankfully there are highway pegs up front, but these only fit riders of a certain size and shape, due partially to the bulbous air cleaner. Passengers protested the tiny rear portion of the seat and the passenger pegs because of the vibration level. One passenger even claimed the seat gave her a hot seat from the vibration, though Harley doesn’t claim any intent. The vibration, however, was never enough to bother riders.

Comfort and performance are easy enough to evaluate, but what about style? It’s especially important on the Sturgis because the Sturgis has style and its style is a major part of what it has to offer. If you saw a Sturgis and were asked to describe it, you might say it’s solid and straightfor-

ward, almost primitive, large and just slightly intimidating. At least that’s what we’d say and its no doubt what Willie G. Davidson had in mind when the bike was styled. So. It looks like what it should look like and that’s successful styling, never mind that forged frame junctions and steel brackets that look as if they were made in somebody’s back yard aren’t in keeping with the style of the other big bikes.

That style is created by the very blackness of the motorcycle. The engine cases and cylinders and heads and all the covers are black, mostly glossy black. So are the

tanks and fenders and the spokes of the cast wheels. The tiniest bit of red trim identifies the Sturgis as a Harley and adds color to the rims of the wheels. Again, it’s all part of that down-home look that Harleys have and others copy.

It’s that look, combined with the staggered beat of the Harley’s engine that manages to make a person on the bike a Harley rider. You don’t need a leather jacket or primary chain holding up your pants, just arrive anywhere on the Sturgis and your presence will be felt. Okay, it may not get you respect.

But it gets you noticed. 0

HARLEY-DAVIDSON

FX8-8C

$5687

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontHere At Cycle World

September 1980 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1980 -

Roundup

RoundupTesting On the Move

September 1980 -

Round-Up

Round-UpMore Recognition

September 1980 -

Round-Up

Round-UpEducational Trail Riding

September 1980 -

Round-Up

Round-UpWhat Fuel Injection Offers For Performance

September 1980 By John Ulrich