CYBERLITE

EVALUATION

When it comes to getting attention, nothing works better than a kick in the butt. One Monday we were visited by an electronics and mathematics engineer named John Voevodsky. He invented, tested and lobbied for an auxiliary brake light, known as the Cyberlite.

It’s an impressive device, Dr. Voevodsky has credentials in the form of four doctorates in scientific fields and and the research looks good.

We were evasively polite. First, we said,

there’s no way we can evaluate a safety item like this. If we rode millions of miles and didn’t get bashed from behind, that would be trying to prove a negative. Second, other research shows being tailgated isn’t a major motorcycle risk. We’ve ridden millions of miles and not been struck from behind. Leave the light here and if we get some time we’ll hook it up and see how it works.

That was Monday. On Thursday one of the crew was on his way back from lunch, sitting in a left turn lane waiting for the

light to change, nice clear day and ... WHACK!

He wasn’t even knocked down, the bike only suffered a broken tail light lens. He walked back to the culprit and asked “Why did you do that?”

“My foot slipped.”

Later that afternoon the Cyberlite was installed on our longterm Honda 750F.

The theory behind the light is intriguing. People don’t always pay conscious attention to what they’re doing, which is another way of saying their foot slipped. Brake lights attract attention but they don’t deliver ways to measure. The light is on, or it’s off, with no distinction between a tap and full on hard.

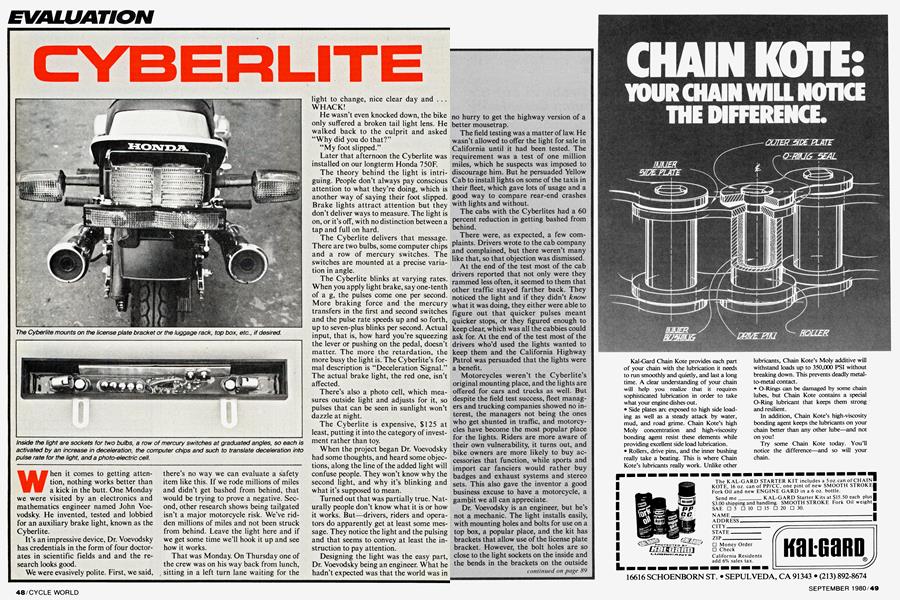

The Cyberlite delivers that message. There are two bulbs, some computer chips and a row of mercury switches. The switches are mounted at a precise variation in angle.

The Cyberlite blinks at varying rates. When you apply light brake, say one-tenth of a g, the pulses come one per second. More braking force and the mercury transfers in the first and second switches and the pulse rate speeds up and so forth, up to seven-plus blinks per second. Actual input, that is, how hard you’re squeezing the lever or pushing on the pedal, doesn’t matter. The more the retardation, the more busy the light is. The Cyberlite’s formal description is “Deceleration Signal.” The actual brake light, the red one, isn’t affected.

There’s also a photo cell, which measures outside light and adjusts for it, so pulses that can be seen in sunlight won’t dazzle at night.

The Cyberlite is expensive, $125 at least, putting it into the category of investment rather than toy.

When the project began Dr. Voevodsky had some thoughts, and heard some objections, along the line of the added light will confuse people. They won’t know why the second light, and why it’s blinking and what it’s supposed to mean.

Turned out that was partially true. Naturally people don’t know what it is or how it works. But—drivers, riders and operators do apparently get at least some message. They notice the light and the pulsing and that seems to convey at least the instruction to pay attention.

Designing the light was the easy part, Dr. Voevodsky being an engineer. What he hadn’t expected was that the world was in no hurry to get the highway version of a better mousetrap.

The field testing was a matter of law. He wasn’t allowed to offer the light for sale in California until it had been tested. The requirement was a test of one million miles, which he suspects was imposed to discourage him. But he persuaded Yellow Cab to install lights on some of the taxis in their fleet, which gave lots of usage and a good way to compare rear-end crashes with lights and without.

The cabs with the Cyberlites had a 60 percent reduction in getting bashed from behind.

There were, as expected, a few complaints. Drivers wrote to the cab company and complained, but there weren’t many like that, so that objection was dismissed.

At the end of the test most of the cab drivers reported that not only were they rammed less often, it seemed to them that other traffic stayed farther back. They noticed the light and if they didn’t know what it was doing, they either were able to figure out that quicker pulses meant quicker stops, or they figured enough to keep clear, which was all the cabbies could ask for. At the end of the test most of the drivers who’d used the lights wanted to keep them and the California Highway Patrol was persuaded that the lights were a benefit.

Motorcycles weren’t the Cyberlite’s original mounting place, and the lights are offered for cars and trucks as well. But despite the field test success, fleet managers and trucking companies showed no interest, the managers not being the ones who get shunted in traffic, and motorcycles have become the most popular place for the lights. Riders are more aware of their own vulnerability, it turns out, and bike owners are more likely to buy accessories that function, while sports and import car fanciers would rather buy badges and exhaust systems and stereo sets. This also gave the inventor a good business excuse to have a motorcycle, a gambit we all can appreciate.

Dr. Voevodsky is an engineer, but he’s not a mechanic. The light installs easily, with mounting holes and bolts for use on a top box, a popular place, and the kit has brackets that allow use of the license plate bracket. However, the bolt holes are so close to the light sockets on the inside and the bends in the brackets on the outside that you must use two open-end wrenches—no room for a socket. The wires aren’t long, six or seven inches, and we had to work to get the hot wire close enough to connect to the brake light wire, and we spliced another length into the ground wire so we could reach a good ground. And the Cyberlite top rubbed the bottom of the Honda’s tail light, solved by gluing a piece of inner tube between the two metal surfaces. The light itself is beautifully done, with components the inventor and his wife buy and assemble in their garage, but installation could be neater.

continued on page 89

continued from pape 49

Findings: We can’t measure our success. We haven’t been rammed since the light was installed, which proves nothing. All we can report is the test done by the taxi fleet.

According to the Hurt Report, most motorcycles are hit in the front, and then on the sides. Only a fraction of injuryrelated bike accidents are from being hit from behind, so if the Cyberlite protects you from that, it’s reduced the risk by less than 10 percent.

We also have philosophical reservations. Another light is more weight, more complication, more bulbs to burn out and wires to fray and current draw from batteries that may be marginal. The federal safety people have shown interest in their usual way, i.e. they won’t buy the rights to the light but they will offer grants and see if they can adopt the principle without using Dr. Voevodsky’s patents, and if a deceleration signal like that was proposed as a law, we’d oppose it.

But we don’t believe in coercion.

We believe in choice, and in safety. The man who was hit from behind and who installed the light and rides with it every day, likes it. No proof, no gain in milesper-gallon, just the feeling that getting the attention of drivers has a value in peace of mind.

He was riding home after installing the light and while stopped in traffic, the man in the car next to him asked, “Is that light stock?”

“No. I put it on myself.”

“Good idea. I was rammed on a bike once.”

Maybe it takes getting hit to appreciate something that may keep you from getting hit.

From: Voevodsky Cyberlite 770 Welch Road, Suite 154 Palo Alto, Calif. 94304 $125 plus $2.50 for shipping and handling

Or: Kieth’s Touring Specialties 41-23 Hampton St. #3F Elmhurst, N.Y. 1 1373 ®

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontHere At Cycle World

September 1980 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1980 -

Roundup

RoundupTesting On the Move

September 1980 -

Round-Up

Round-UpMore Recognition

September 1980 -

Round-Up

Round-UpEducational Trail Riding

September 1980 -

Round-Up

Round-UpWhat Fuel Injection Offers For Performance

September 1980 By John Ulrich