KAWASAKI KZ440-D1 BELT DRIVE

CYOLE WORLD TEST

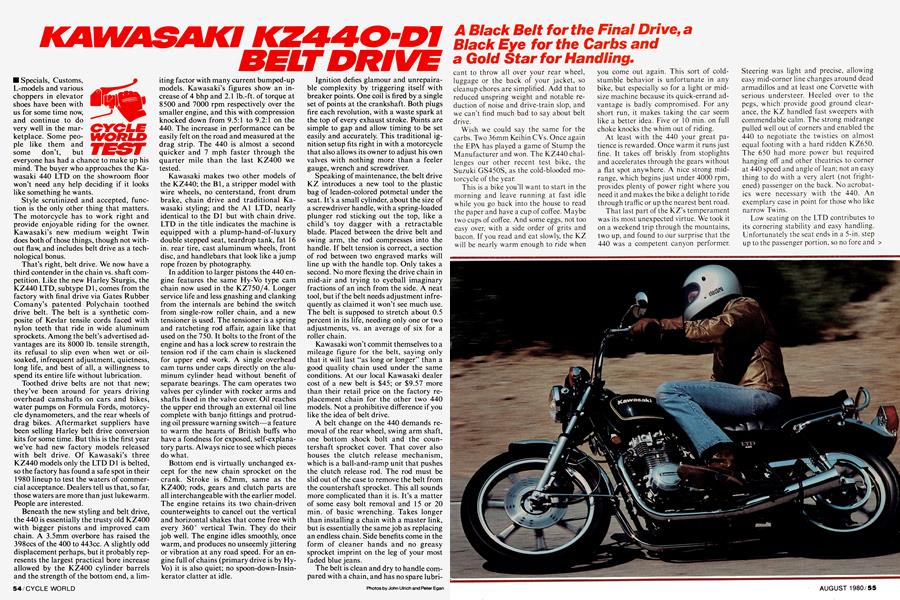

Specials, Customs, L-models and various choppers in elevator shoes have been with us for some time now, and continue to do very well in the marketplace. Some people like them and some don't, but everyone has had a chance to make up his mind. The buyer who approaches the Kawasaki 440 LTD on the showroom floor won't need any help deciding if it looks like something he wants.

Style scrutinized and accepted, function is the only other thing that matters. The motorcycle has to work right and provide enjoyable riding for the owner. Kawasaki’s new medium weight Twin does both of those things, though not without flaw, and includes belt drive as a technological bonus.

That’s right, belt drive. We now have a third contender in the chain vs. shaft competition. Like the new Harley Sturgis, the KZ440 LTD, subtype Dl, comes from the factory with final drive via Gates Rubber Comany’s patented Polychain toothed drive belt. The belt is a synthetic composite of Kevlar tensile cords faced with nylon teeth that ride in wide aluminum sprockets. Among the belt’s advertised advantages are its 8000 lb. tensile strength, its refusal to slip even when wet or oilsoaked, infrequent adjustment, quietness, long life, and best of all, a willingness to spend its entire life without lubrication.

Toothed drive belts are not that new; they’ve been around for years driving overhead camshafts on cars and bikes, water pumps on Formula Fords, motorcycle dynamometers, and the rear wheels of drag bikes. Aftermarket suppliers have been selling Harley belt drive conversion kits for some time. But this is the first year we’ve had new factory models released with belt drive. Of Kawasaki’s three KZ440 models only the LTD Dl is belted, so the factory has found a safe spot in their 1980 lineup to test the waters of commercial acceptance. Dealers tell us that, so far, those waters are more than just lukewarm. People are interested.

Beneath the new styling and belt drive, the 440 is essentially the trusty old KZ400 with bigger pistons and improved cam chain. A 3.5mm overbore has raised the 398ccs of the 400 to 443cc. A slightly odd displacement perhaps, but it probably represents the largest practical bore increase allowed by the KZ400 cylinder barrels and the strength of the bottom end, a limiting factor with many current bumped-up models. Kawasaki’s figures show an increase of 4 bhp and 2.1 lb.-ft. of torque at 8500 and 7000 rpm respectively over the smaller engine, and this with compression knocked down from 9.5:1 to 9.2:1 on the 440. The increase in performance can be easily felt on the road and measured at the drag strip. The 440 is almost a second quicker and 7 mph faster through the quarter mile than the last KZ400 we tested.

Kawasaki makes two other models of the KZ440; the BÍ, a stripper model with wire wheels, no centerstand, front drum brake, chain drive and traditional Kawasaki styling; and the AÍ LTD, nearly identical to the Dl but with chain drive. LTD in the title indicates the machine is equipped with a plump-hand-of-luxury double stepped seat, teardrop tank, fat 16 in. rear tire, cast aluminum wheels, front disc, and handlebars that look like a jump rope frozen by photography.

In addition to larger pistons the 440 engine features the same Hy-Vo type cam chain now used in the KZ750/4. Longer service life and less gnashing and clanking from the internals are behind the switch from single-row roller chain, and a new tensioner is used. The tensioner is a spring and ratcheting rod affair, again like that used on the 750. It bolts to the front of the engine and has a lock screw to restrain the tension rod if the cam chain is slackened for upper end work. A single overhead cam turns under caps directly on the aluminum cylinder head without benefit of separate bearings. The cam operates two valves per cylinder with rocker arms and shafts fixed in the valve cover. Oil reaches the upper end through an external oil line complete with banjo fittings and protruding oil pressure warning switch—a feature to warm the hearts of British buffs who have a fondness for exposed, self-explanatory parts. Always nice to see which pieces do what.

Bottom end is virtually unchanged except for the new chain sprocket on the crank. Stroke is 62mm, same as the KZ400; rods, gears and clutch parts are all interchangeable with the earlier model. The engine retains its two chain-driven counterweights to cancel out the vertical and horizontal shakes that come free with every 360° vertical Twin. They do their job well. The engine idles smoothly, once warm, and produces no unseemly jittering or vibration at any road speed. For an engine full of chains (primary drive is by HyVo) it is also quiet; no spoon-down-Insinkerator clatter at idle.

Ignition defies glamour and unrepairable complexity by triggering itself with breaker points. One coil is fired by a single set of points at the crankshaft. Both piugs fire each revolution, with a waste spark at the top of every exhaust stroke. Points are simple to gap and allow timing to be set easily and accurately. This traditional ignition setup fits right in with a motorcycle that also allows its owner to adjust his own valves with nothing more than a feeler gauge, wrench and screwdriver.

Speaking of maintenance, the belt drive KZ introduces a new tool to the plastic bag of leaden-colored potmetal under the seat. It’s a small cylinder, about the size of a screwdriver handle, with a spring-loaded plunger rod sticking out the top, like a child’s toy dagger with a retractable blade. Placed between the drive belt and swing arm, the rod compresses into the handle. If belt tension is correct, a section of rod between two engraved marks will line up with the handle top. Only takes a second. No more flexing the drive chain in mid-air and trying to eyeball imaginary fractions of an inch from the side. A neat tool, but if the belt needs adjustment infrequently as claimed it won’t see much use. The belt is supposed to stretch about 0.5 percent in its life, needing only one or two adjustments, vs. an average of six for a roller chain.

Kawasaki won’t commit themselves to a mileage figure for the belt, saying only that it will last “as long or longer’’ than a good quality chain used under the same conditions. At our local Kawasaki dealer cost of a new belt is $45; or $9.57 more than their retail price on the factory replacement chain for the other two 440 models. Not a prohibitive difference if you like the idea of belt drive.

A belt change on the 440 demands removal of the rear wheel, swing arm shaft, one bottom shock bolt and the countershaft sprocket cover. That cover also houses the clutch release mechanism, which is a ball-and-ramp unit that pushes the clutch release rod. The rod must be slid out of the case to remove the belt from the countershaft sprocket. This all sounds more complicated than it is. It’s a matter of some easy bolt removal and 15 or 20 min. of basic wrenching. Takes longer than installing a chain with a master link, but is essentially the same job as replacing an endless chain. Side benefits come in the form of cleaner hands and no greasy sprocket imprint on the leg of your most faded blue jeans.

The belt is clean and dry to handle compared with a chain, and has no spare lubricant to throw all over your rear wheel, luggage or the back of your jacket, so cleanup chores are simplified. Add that to reduced unspring weight and notable reduction of noise and drive-train slop, and we can’t find much bad to say about belt drive.

A Black Belt for the Final Drive, a Black Eye for the Carbs and a Gold Star for Handling.

Wish we could say the same for the carbs. Two 36mm Keihin CVs. Once again the EPA has played a game of Stump the Manufacturer and won. The KZ440 challenges our other recent test bike, the Suzuki GS450S, as the cold-blooded motorcycle of the year.

This is a bike you’ll want to start in the morning and leave running at fast idle while you go back into the house to read the paper and have a cup of coffee. Maybe two cups of coffee. And some eggs, not too easy over, with a side order of grits and bacon. If you read and eat slowly, the KZ will be nearly warm enough to ride when you come out again. This sort of coldstumble behavior is unfortunate in any bike, but especially so for a light or midsize machine because its quick-errand advantage is badly compromised. For any short run, it makes taking the car seem like a better idea. Five or 10 min. on full choke knocks the whim out of riding.

At least with the 440 your great patience is rewarded. Once warm it runs just fine. It takes off briskly from stoplights and accelerates through the gears without a flat spot anywhere. A nice strong midrange, which begins just under 4000 rpm, provides plenty of power right where you need it and makes the bike a delight to ride through traffic or up the nearest bent road.

That last part of the KZ’s temperament was its most unexpected virtue. We took it on a weekend trip through the mountains, two up, and found to our surprise that the 440 was a competent canyon performer. Steering was light and precise, allowing easy mid-corner line changes around dead armadillos and at least one Corvette with serious understeer. Heeled over to the pegs, which provide good ground clearance, the KZ handled fast sweepers with commendable calm. The strong midrange pulled well out of corners and enabled the 440 to negotiate the twisties on almost equal footing with a hard ridden KZ650. The 650 had more power but required hanging off and other theatrics to corner at 440 speed and angle of lean; not an easy thing to do with a very alert (not frightened) passenger on the back. No acrobatics were necessary with the 440. An exemplary case in point for those who like narrow Twins.

Fow seating on the FTD contributes to its cornering stability and easy handling. Unfortunately the seat ends in a 5-in. step up to the passenger portion, so no fore and > aft rider movement is possible. You sit down on the bike and that’s where you'll remain until you get off, backache or no. As cruisin’ style motorcycles go, however, the LTD offers better than average comfort. The bucko bars terminate at a fairly natural wrist position and the footpegs are not absurdly far forward. The seat, which Kawasaki advertises as “dual-density foam rubber,’’ does its job well enough so you don’t notice it’s there. Absence of pain is a high accolade in the world of motorcycle seats.

Our passengers reported a similar comfort level, but complained that the novelty of good forward vision from the grandstand rear seat wore off as wind fatigue and howling helmet noise set in. One of our test riders, an older person, also mentioned that the footpegs were too close to the low seat and caused a cramping of the legs, though no one else noticed the problem.

The belt drive LTD uses a final reduction ratio of 2.72:1 rather than the 3.00:1 on the chain drive model. This slightly higher gearing makes the belted LTD a relatively serene cruiser on the open road. Counterbalancing and the less frequent firing pulses of the Twin (vs. Four) enhance the feeling. The Kawasaki also projects a slightly different exhaust note and engine resonance than the other Japanese midsize Twins; it produces a rumbling rather than a whirring sound, giving it just a hint of Big Bike ambiance.

Shift lever action is succinct and positive, and we have to give Kawasaki a gold star for leaving off the dreaded starter/ clutch interlock. You can start the 440 and operate the choke (which certainly needs to be operated) using only two hands. The six-speed transmission has a positive neutral finder to keep you from kicking back and forth between 1st and 2nd in diligent search of a green dash light. On our test bike it was possible, with a little fiddling, to shift from neutral to 2nd with the engine off, unlike most bikes with a neutral finder. A good thing, because when the battery runs down there is no kick starter, and 2nd gear is best for bump starts.

Out on the open road we were frequently surprised to find a leftover gear while upshifting; a nice change after some of the more buzzy Fours which leave you stabbing for another cog that isn’t there. The D1 is geared better for road riding than it is for the killer quarter mile.

Which is why it’s the slowest of the 400 to 450cc road bikes we’ve tested. The Honda CB400T Hawk and the Yamaha XS400F are both marginally quicker in the quarter mile, though the KZ is about 2 mph faster, at 88.06 mph, than the Yamaha. The Suzuki GS450S is a second quicker and 6 mph faster through the traps. All those bikes are geared lower, however, and consequently cruise at higher rpm in top gear. Both chain driven models of the 440 are likely to be quicker, but judging the 440 LTD on its drag strip times is a little misleading. We’ve tested a couple of bikes this year whose all-ornothing carburetion and high power band have made them fast, but unpleasant to ride in traffic. The 440, in keeping with its marketing profile, provides a strong, more laid-back midrange and power where you need it.

Brakes on the 440 are predictable and hard-stopping. In fact they hauled the bike down from 60 mph faster than anything in class, the 129 ft. stop nipping 2 ft. off the late Yamaha RD400’s old record. Not bad for a single disc and rear drum. The 440 weighed in at 390 lb. with half a tank of fuel, which makes it exactly the same weight as the Yamaha XS400F and the 1968 Triumph 650 Bonneville (as long as we’re talking vertical Twins), 8 lb. lighter than the 400 Hawk and a full 32 lb. less than the Suzuki GS450S.

Relative lightness, as well as lean jetting, did no harm to the KZ’s mileage. We got 66.4 mpg on our normal test loop and 60.5 mpg flogging the bike two-up on a long climb through the mountains. The 3.2 gal. tank is not overly large in this era of the closed gas pump. A pity, because the teardrop tank could probably stand enlarging without damage to its clean lines. The tank gives you 156 miles before stumbling over reserve and another 54 after that. The more traditional BÍ model of the 440 has a 3.7 gal. tank, which is no giant but adds another 33 miles in range. The BÍ is also 22 lb. lighter than the LTD, which should give mileage another boost, or at least allow for a larger, better-fed passenger.

Overall, the 440 works pretty well. The belt drive seems like a good idea, and the local dealer tells us he has more orders for this model than he can fill. What the bike does not do well, of course, is warm up and run without reminding the owner that life is slipping by, summer is short, and youth is ephemeral. It takes too long; a problem which hovers on the un side of acceptability. Warmup is a hassle the owner is going to have to face every time he takes a ride, and after a while it’s going to get old. Kawasaki, of all manufacturers, has generally done the best work meeting emission laws and retaining good rideability. The KZ550, 650, 750, 1000 and 1300 are all much better than the 440, so Kawasaki knows how to make good running bikes. Perhaps if the KZ440 used Kawasaki’s air suction emission system the carb jetting could be richer and the warmup would be quicker.

Beyond that, the 440 grew on us, its function outweighing the style. After riding sport bikes that don't handle as well as the 440, cruisers that aren’t as comfortable as the 440, big bikes that can't carry two people as easily as the 440 and small bikes that use more gas than the 440, it’s hard not to like the small Kawasaki. In spite of the carburetion. E3

KAWASAKI

KZ440-D1 BELT DRIVE

$1829

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

August 1980 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1980 -

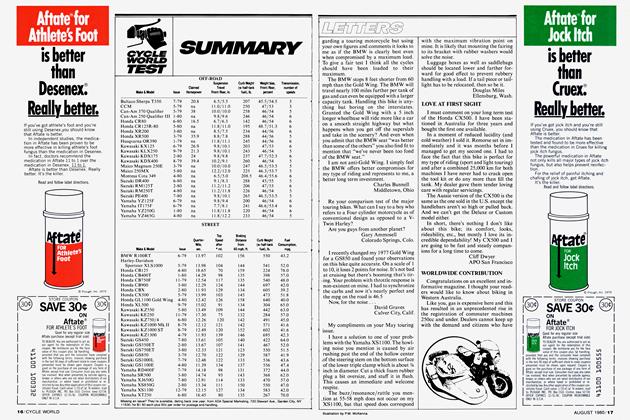

Departments

DepartmentsSummary

August 1980 -

Books

BooksAmerican Racer

August 1980 By Henry N. Manney III -

Books

BooksRestoring And Tuning of Classic Motorcycles

August 1980 By Henry N. Manney III -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

August 1980 By Henry N. Manney III