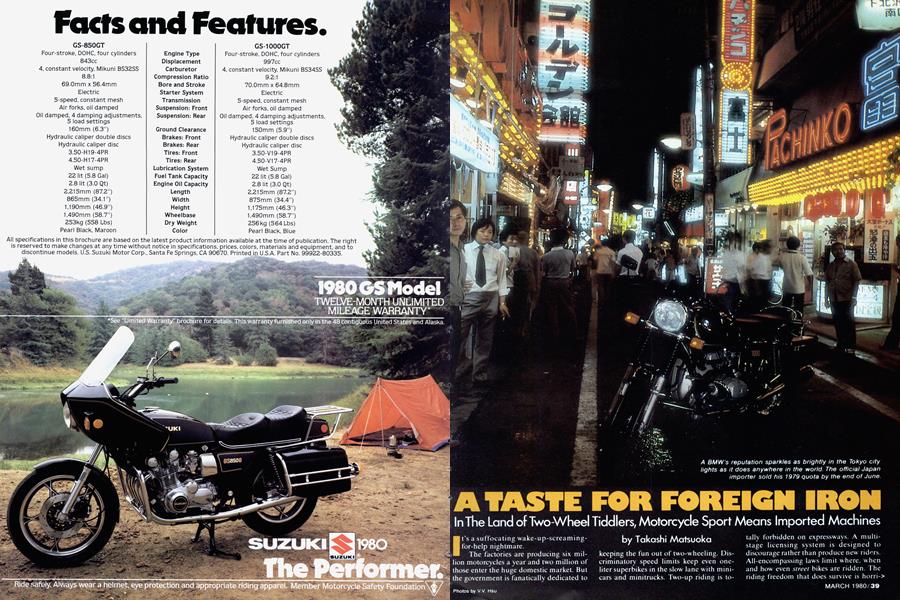

A TASTE FOR FOREIGN IRON

In The Land of Two-Wheel Tiddlers, Motorcycle Sport Means Imported Machines

Takashi Matsuoka

It's a suffocating wake-up-screamingfor-help nightmare.

The factories are producing six million motorcycles a year and two million of those enter the huge domestic market. But the government is fanatically dedicated to keeping the fun out of two-wheeling. Discriminatory speed limits keep even oneliter superbikes in the slow lane with minicars and minitrucks. Two-up riding is totally forbidden on expressways. A multistage licensing system is designed to discourage rather than produce new riders. All-encompassing laws limit where. when and how even street bikes are ridden. The riding freedom that does survive is horri->

bly restricted by Sunday gas station closures and prices rapidly approaching $3 per gallon. And of those two million motorcycles that feed home demand, a mere 4 percent displace more than 250cc.

The scenario for the ultimate motorcycle horror movie? Unfortunately for Japanese enthusiasts, these are simply the facts of life. The nation that is the home of the world’s most prolific producers of motorcycles is not a congenial place to ride them. This particular horror flick is undeniably real.

American riders who have lately begun to fear the worst for the future of their sport will consider how things have gone in Japan and shudder. But even in the grimmest of situations, there is hope. One would hardly expect such a place to be seething with passion for foreign exotica, yet makes like Malanca, Moto Morini, Benelli and Cimatti have helped increase the outsiders’ share from a paltry 437 in 1968 to over 7000 in 1978, a sixteen-fold increase despite limited availability and high prices. Motorcyclists everywhere tend to like the rare and unusual, but those in Japan are absolutely fervid in their lust for—irony of ironies—imported machines.

Hisao Kawana is sales manager for Murayama Motors, one of the largest import dealers there. “Japanese riders are zealous in their pursuit of motorcycling pleasure,” he says, “but those who prefer foreign makes are unusually enthusiastic even by Japanese standards.” This high level of enthusiasm allows Kawana to place bikes on his showroom floor that many people outside of Europe have never even heard of, much less seen. You want a Zundapp KS50 water-cooled two-stroke Single with alloy wheels? $2000 will produce instant delivery. How about a more mundane Spanish-made Ducati 500 Twin? Or a gleaming black 30th Anniversary Laverda Jota 1200 with triple drilled discs, minifairing, black chrome pipes and gold anodized wheels? A brand-new MV Agusta 750S? A Moto Guzzi 254 Four? “We try to keep a decent selection on hand,” Kawana says modestly.

You are thinking, perhaps, that buyers of such rarities will find themselves up that proverbial dark and dirty creek when the time comes for service and repair. But in Japan, a dealer who fails to fulfill the unspoken but absolute obligation to keep the customer happy has committed business hara-kiri. The typical import dealer has a service department with more area than its showroom and employs more mechanics than salesmen. Thus, the owner of a Desmo Ducati will find tea, sympathy and proper mechanical attention should his valve train, for example, require expert care. Ah so, things are different in the East sometimes, yes ?

But if buying a Desmo is not mechanically risky, it is expensive. A Ducati 350 Single costs nearly $4000. A 900SS, like the one Yoshitaka Chida recently bought, will put a $6000 dent in the purchaser’s bank

account. “That’s about two-thirds of my annual salary,” he says calmly. Chida works for the family business, Chida Hard Liquors, but doesn’t seem to be the type to indulge much in alcoholic diversions. He is very calm, deliberate and serious. The clipons, he tells me, present no comfort problem. “I have been training for the past several months.” Training? “Yes. I do fifty push-ups and sit-ups each morning and night, and run several miles daily. I can ride all day without difficulty.”

“People who purchase imported motorcycles here are not flighty kids, they are mature men,” says H.R. Fernandes, vice president of Balcom Trading, official distributor for BMW and Harley-Davidson in Japan. “They have to be in order to have the necessary economic standing to enable them to make the purchase. And mature men do not do things lightly. They are serious about their sport, very serious.” Fernandes, a mature man himself, neglects to include a rapidly growing segment of the market—mature women.

“1 don’t like riding on the back,” Chikako Watanabe tells me. “It gets very tiresome.” A further sign of how rapidly things are changing in the supposedly eternal East is the fact that Chikako bought her yellow Ducati 350 by using her boyfriend’s Kawasaki 750 as down payment.

“Let me get this straight,” I say. “You mean your boyfriend took your old 400 for his own use and traded in his new 750 so you could get a Ducati?”

“Why not?” she answers blithely. “I’m a good rider. I know how to appreciate a first-class machine.”

Confused by this apparent collapse of tradition in my ancestral homeland, I seek out someone who can provide some insight. The most dedicated and knowledgeable motorcyclists anywhere are often those with British bikes; perhaps because the idiosyncrasies of those machines make dedication and knowledge requirements of continued mobility. As the rider of a British bike no longer in production, a Norton 850, Shigenao Negishi possesses even

more of those qualities than most.

He laughs when I tell him about Chikako and takes another hit of saké. “Everything changes,” he declares, “but Japan is still Japan.” He pauses and considers the aftertaste. “Or perhaps it’s the other way around. Mmmm. In any case, this is not a cultural matter at all. The man in question is simply not a dedicated motorcyclist. No one who is—whether man or woman—would sacrifice his or her own motorcycle for someone else’s riding pleasure.” He laughs heartily at my startled expression. “It’s true, isn’t it? There is an irreducible core of motorcycle selfishness. Would you give up your machine for a lesser one so your lover could have a better one?” He laughs aloud at the thought. “There are fools everywhere, Matsuoka.”

Aware that I have received the benefit of an elder’s wisdom, I return to the streets in a better frame of mind despite my instant saké hangover.

“I don’t know that I should talk to you,” Masashi Yoshihara tells me. “It’s some->

what distasteful for me. a Japanese, to allow himself to be photographed with a foreign motorcycle, isn’t it?”

Yoshihara is the only rider I have interviewed who expresses this view. “Why?” I ask. “Are you ashamed of your choice?” His hand reflexively moves to the seat of his red MV Agusta 350S. “Of course not. MV Agusta is the finest name in the history of motorcycling. This particular machine, with its light but not insubstantial look, is as much a work of art as it is a vehicle.” He stops and fixes his attention on the gauges. “MV is a very good name,” he repeats.

But didn’t he think $3800 was a trifle high for a 350, even one with a good name?

“A somewhat high price,” he agrees, “but not an outrageously high one. It’s better to pay the price and get the best than to compromise and remain unsatisfied.” Yoshihara’s view of prices is one generally shared by Japanese import buyers. And like him, few equate piston displacement with value. It is not considered strange to pay more for a 350 than a 750. Aji— flavor—is by far the most important consideration. There is almost no other consideration for my mentor Negishi’s Bonneville-riding friend. Akio Sato.

“Triumphs contain more of the motorcycle essence than any other make,” he says passionately. “It better embodies the very concept ‘motorcycle’ than any other two motorcycles put together.”

“You’re entitled to your opinion.” Negishi tells him, “but I know how you feel after two hours on the expressway. My Norton is comfortable. And the engine is strong, unbreakable.”

“Really?” Sato says. “If your Norton is so good, why do you have a BMW for a backup bike?”

“You have a BMW, too?” I say. Negishi hasn’t told me about this. Ever since 1 met him, he’s done nothing but sing rhapsodic paeans to the Norton mystique. I almost feel betrayed. “Why?”

“I’ve only had it for a few months,” Negishi replies, as if that lessens the fact of his possession. “I looked at it and tested it and was very impressed. I thought, ‘what a fine machine’. It is, but somehow it isn’t much fun to ride. I guess it isn’t as good as I thought it was.”

Japanese BMW loyalists, like those anywhere. would strongly disagree, and do.

“It’s even better than I expected.” Taiki Yaegashi says of his R100RS. “The ride is amazingly comfortable. And handling does not suffer when carrying a passenger.” Which he often does. I feel guilty about the sense of relief I feel when his companion, Yuko Hirano, tells me she actually prefers riding on the buddy seat. “It's very relaxing. Sometimes I can almost fall asleep and dream.” The R100RS is one of the few bargains in this market. At $8000. it is barely 10 percent more than the typical U.S. out-the-door price. “The main reason I got this model was the fairing,” Yaegashi says. Japan’s anti-modification laws are so stringent that even adding a fairing can result in polite but persistent police harassment. I point out that Harley FLHs also have fairings. Why not an FLH?

Yaegashi and Yuko look at each other and smile. “I used to have one,” he confesses. “It was the most terrible purchase I ever made. I had problem after problem with it.”

“It may be true that Harleys have more than the usual amount of trouble.” Takao Yamazaki admits. “But my Sportster is still the best motorcycle I’ve ever ridden. It provides a kind of visceral reward that is totally lacking in other makes.” Then he says, with a somewhat self-mocking smile,"But perhaps the main reason I get so much pleasure from my Sportster is because everyone else is riding Japanese motorcycles.”

And that reason—a truly bizarre one when you hear it in Japan spoken in the Japanese language—is probably as good as any. The reason for riding a particular machine—Ducati or Honda, Norton or BMW—is locked in the secret heart of every rider. In the final analysis, aji—flavor— is the deciding factor.

One of the salesmen for Murayama Motors has the superbly ironic name of Akira Kawasaki. “One of my customers traded in a CBX,” he tells me. Like all Japanese motorcycles displacing more than 750cc's, CBXs must be exported and reimported to be sold legally. They are therefore expensive and rare. “But it was only fast, that's all. It had no distinct flavor.”

“And what do you ride?” I ask. genuinely curious. A Zundapp? A Moto Morini? A Malanca?

His shoulders slump and his cheeks redden perceptibly. “A Yamaha 750.” he says softly. “But I’m saving for a Ducati.” He sees me smiling. “What do you ride?”

“Ah, actually, well,” I stutter. “I don’t really have a bike just now.” His eyes begin to flash in triumph. “But I'm saving for a Yamaha 750.”

We stop in the middle of the crosswalk and look into each other’s eyes. Then we both laugh loudly. Luckily, the light is on our side.

“Come on.” he says, “I’ll treat you to a bowl of Chinese noodles. I know a place nearby that makes them with a wonderful foreign flavor.”

We walk together in search of aji of a different kind. 13

View Full Issue

View Full Issue