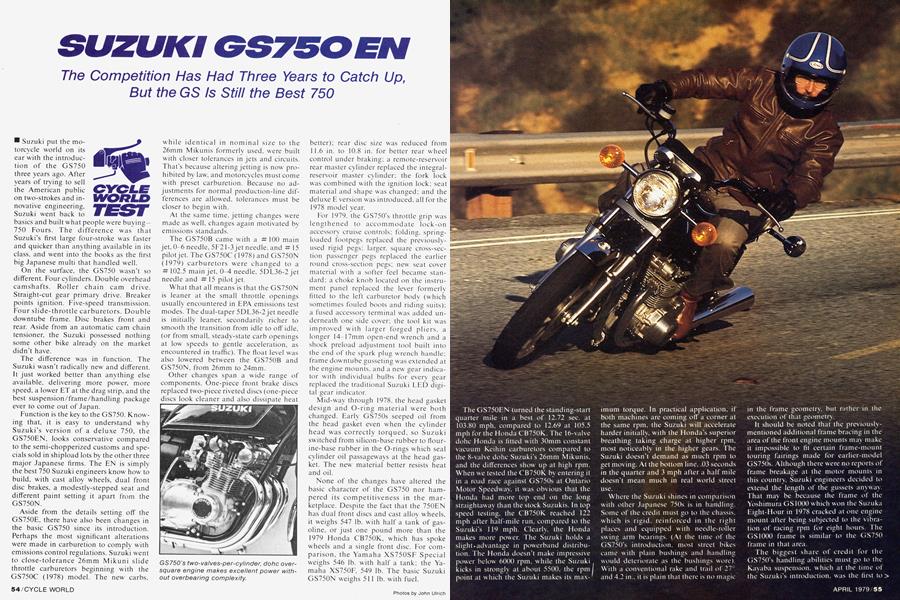

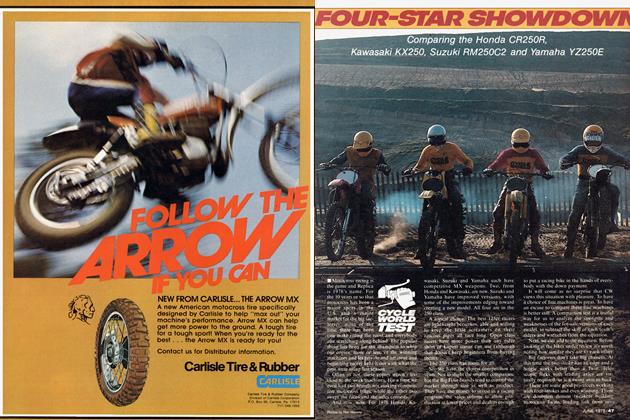

SUZUKI GS750 EN

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The Competition Has Had Three Years to Catch Up, But the GS Is Still the Best 750

Suzuki put the motorcycle world on its ear with the introduction of the GS750 three years ago. After years of trying to sell the American public on two-strokes and innovative engineering, Suzuki went back to basics and built what people were buying—750 Fours. The difference was that Suzuki’s first large four-stroke was faster and quicker than anything available in its class, and went into the books as the first big Japanese multi that handled well.

On the surface, the GS750 wasn't so different. Four cylinders. Double overhead camshafts. Roller chain cam drive. Straight-cut gear primary drive. Breaker points ignition. Five-speed transmission. Four slide-throttle carburetors. Double downtube frame. Disc brakes front and rear. Aside from an automatic cam chain tensioner, the Suzuki possessed nothing some other bike already on the market didn't have.

The difference was in function. The Suzuki wasn't radically new and different. It just worked better than anything else available, delivering more power, more speed, a lower ET at the drag strip, and the best suspension/frame/handling package ever to come out of Japan.

Function is the key to the GS750. Knowing that, it is easy to understand why Suzuki’s version of a deluxe 750, the GS750EN, looks conservative compared to the semi-chopperized customs and specials sold in shipload lots by the other three major Japanese firms. The EN is simply the best 750 Suzuki engineers know how to build, with cast alloy wheels, dual front disc brakes, a modestly-stepped seat and different paint setting it apart from the GS750N.

Aside from the details setting off the GS750E, there have also been changes in the basic GS750 since its introduction. Perhaps the most significant alterations were made in carburetion to comply with emissions control regulations. Suzuki went to close-tolerance 26mm Mikuni slide throttle carburetors beginning with the GS750C (1978) model. The new carbs. while identical in nominal size to the 26mm Mikunis formerly used, were built with closer tolerances in jets and circuits. That's because altering jetting is now prohibited by law. and motorcycles must come with preset carburetion. Because no adjustments for normal production-line differences are allowed, tolerances must be closer to begin with.

At the same time, jetting changes were made as well, changes again motivated by emissions standards.

The GS750B came with a # 100 main jet, 0-6 needle, 5F21-3 jet needle, and # 15 pilotjet. The GS750C (1978) and GS750N (1979) carburetors were changed to a # 102.5 main jet, 0-4 needle. 5DL36-2 jet needle and #15 pilotjet.

What that all means is that the GS750N is leaner at the small throttle openings usually encountered in EPA emissions test modes. The dual-taper 5DL36-2 jet needle is initially leaner, secondarily richer to smooth the transition from idle to oft'idle, (or from small, steady-state carb openings at low speeds to gentle acceleration, as encountered in traffic). The float level was also lowered between the GS750B and GS750N, from 26mm to 24mm.

Other changes span a wide range of components. One-piece front brake discs replaced two-piece riveted discs (one-piece discs look cleaner and also dissipate heat better); rear disc size was reduced from 11.6 in. to 10.8 in. for better rear wheel control under braking; a remote-reservoir rear master cylinder replaced the integralreservoir master cylinder; the fork lock was combined with the ignition lock; seat material and shape was changed; and the deluxe E version was introduced, all for the 1978 model year.

For 1979. the GS750's throttle grip was lengthened to accommodate lock-on accessory cruise controls; folding, springloaded footpegs replaced the previouslyused rigid pegs; larger, square cross-section passenger pegs replaced the earlier round cross-section pegs; new seat cover material with a softer feel became standard; a choke knob located on the instrument panel replaced the lever formerly fitted to the left carburetor body (which sometimes fouled boots and riding suits); a fused accessory terminal was added underneath one side cover; the tool kit was improved with larger forged pliers, a longer 14 17mm open-end wrench and a shock preload adjustment tool built into the end of the spark plug wrench handle; frame downtube gusseting was extended at the engine mounts, and a new gear indicator with individual bulbs for every gear replaced the traditional Suzuki LED digital gear indicator.

Mid-way through 1978, the head gasket design and O-ring material were both changed. Early GS750s seeped oil from the head gasket even when the cylinder head was correctly torqued, so Suzuki switched from silicon-base rubber to flourine-base rubber in the O-rings which seal cylinder oil passageways at the head gasket. The new material better resists heat and oil.

None of the changes have altered the basic character of the GS750 nor hampered its competitiveness in the marketplace. Despite the fact that the 750EN has dual front discs and cast alloy wheels, it weighs 547 lb. with half a tank of gasoline, or just one pound more than the 1979 Honda CB750K, which has spoke wheels and a single front disc. For comparison, the Yamaha XS750SF Special weighs 546 lb. with half a tank; the Yamaha XS750F, 549 lb. The basic Suzuki GS750N weighs 511 lb. with fuel.

TheGS750EN turned the standing-start quarter mile in a best of 12.72 sec. at 103.80 mph. compared to 12.69 at 105.5 mph for the Honda CB750K. The 16-valve dohc Honda is fitted with 30mm constant vacuum Keihin carburetors compared to the 8-valve dohc Suzuki's 26mm Mikunis, and the differences show up at high rpm. When we tested the CB750K by entering it in a road race against GS750s at Ontario Motor Speedway, it was obvious that the Honda had more top end on the long straightaway than the stock Suzukis. In top speed testing, the CB750K reached 122 mph after half-mile run, compared to the Suzuki's 119 mph. Clearly, the Honda makes more power. The Suzuki holds a slight.advantage in powerband distribution. The Honda doesn't make impressive power below 6000 rpm, while the Suzuki kicks in strongly at about 5500. the rpm point at which the Suzuki makes its maximum torque. In practical application, if both machines are coming off a corner at the same rpm. the Suzuki will accelerate harder initially, with the Honda's superior breathing taking charge at higher rpm. most noticeably in the higher gears. The Suzuki doesn't demand as much rpm to get moving. At the bottom line. .03 seconds in the quarter and 3 mph after a half mile doesn't mean much in real world street use.

Where the Suzuki shines in comparison with other Japanese 750s is in handling. Some of the credit must go to the chassis, which is rigid, reinforced in the right places and equipped with needle-roller swing arm bearings. (At the time of the GS750's introduction, most street bikes came with plain bushings and handling would deteriorate as the bushings wore). With a conventional rake and trail of 27 and 4.2 in., it is plain that there is no magic in the frame geometry, but rather in the execution of that geometry.

It should be noted that the previouslymentioned additional frame bracing in the area of the front engine mounts may make it impossible to fit certain frame-mount touring fairings made for earlier-model GS75ÖS. Although there were no reports of frame breakage at the motor mounts in this country, Suzuki engineers decided to extend the length of the gussets anyway. That may be because the frame of the Yoshimura GS1000 w hich won the Suzuka Eight-Hour in 1978 cracked at one engine mount after being subjected to the vibration of racing rpm for eight hours. 1 he GS1000 frame is similar to the GS750 frame in that area.

The biggest share of credit for the GS750’s handling abilities must go to the Kayaba suspension, which at the time ol the Suzuki's introduction, was the first to offer both compliance for rider comfort and high-speed control and handling for rider thrills. Even today, the Suzuki has the best suspension available on a 750.

The front forks, for example, respond well to small, repetitive bumps—such as concrete road expansion joints—isolating the rider from the series of small jolts. Yet it deals with large bumps equally as well. The shocks, while not as compliant as the forks, also respond well to a full range of road irregularities. How' good the shock compliance seemed depended upon the road and load. One 140-lb. tester thought the ride over one section of concrete freeway choppier than he would have liked, even at the lowest preload setting. But heavier staffers had no quarrel with the ride, and it did take a particularly foul section of expansion joints to cause the 140-lb. tester to complain. Anyone who ever rode the seemingly-locked shocks of a Suzuki Triple of any size will immediately notice the improvement in the GS shocks— the difference is like night and day, or maybe like going from a rigid rear end to swing arm suspension.

The price one pays for compliance is instantaneous fork dive under braking, due to little compression damping. But it is a small price to pay indeed, for in spite of the compliant forks and shocks the Suzuki handles the rigors of the racetrack better than its competition. Where the CB750K wallows in transitions from braking to accelerating while still leaned over, the GS750 doesn’t; where the CB750K shakes its head down the straightaway, the Suzuki runs true. The GS750 can be improved upon for the racetrack through the addition of accessory shocks, since the Stockers will heat up and fade and allow some rearend pogo under heavy loading after several hot laps. But taken within the context of standard equipment, the Suzuki still comes out best in the 750 class, with fewer and less severe defects in handling under pressure than any of its competitors. What’s more, it takes longer in terms of laps or time spent chasing down a curvy stretch of pavement before the slight defects surface.

When pressed, the GS750 drags the center and side stands on the left side and the centerstand on the right, followed by the footpegs and exhaust pipes if the rider is really pushing it. It’s possible to ride very hard on the stock tires. The OEM IRC Grand High Speed GS11-AW front and rear tires were rated Very Good in CYCLE WORLD’S tire tests (August 1978, January 1979) for good reason. For most sporting use the GS750EN has good cornering clearance, and it will take a hot shoe rider with the gas on to find the limits of that clearance.

For more sedate use, as on the highway, the GS750’s seat matches its suspension and is a vast improvement over early model seats. It’s wide enough with a good balance between soft and firm to keep the rider comfortable on long hauls. Seating position is a matter of personal preferences, and the GS wheelbarrow handlebars have earned paragraph upon paragraph of scorn from road testers since the bike’s introduction. But while go-fasters may prefer lower and farther-forward bars, people interested in riding behind a fairing or windshield will find the stock bars to be just right. Most, however, will agree that the footpegs are a bit high and forward. It’s something you can get used to.

Where there’s go, there must be stop and again the Suzuki shines. The latest Hondas are equipped with new pad materials to improve wet-weather braking, but the pads squeal and discolor the discs, and feed back a pulsation through the brake lever. At slower speeds, recent Honda brakes feel as if they're being applied and released even though the rider is maintaining steady pressure. Meanwhile, Kawasaki is drilling asymetrical patterns in 1979 model discs and also changing pad material for wet-weather stopping. But Suzuki, in spite of factory claims that pad material hasn’t been changed since the GS750’s introduction, has the most responsive, controllable and powerful disc brakes in the business, both wet and dry. The pads don’t squeal and squall, the discs don’t discolor excessively, the rider doesn’t have to put up with annoying pulsating or grabbiness. You want to stop? Apply the brakes, and you'll stop. The Suzuki GS750EN stops from an actual 60 mph in 141 feet. What isn’t apparent from looking at the stopping distance is the fact that the Suzuki will stop at that distance time after time without the rider fearing for his life. That isn’t a hangi t-out-on-t he-edge-of-d isas ter stop, but rather a perfectly controllable, repeatable stop, no mean engineering feat. In a pouring-rain foray, we found no problems in bringing the GS750 to a safe, predictable stop in spite of water running off the discs and calipers the whole time.

But while the Suzuki holds clear advantages in the areas of handling and braking—especially braking control —it falls short of the class standard in transmission shifting. The Suzuki’s transmission doesn't jump out of gear, lodge itself into false neutrals or bypass the desired gear and slam into one higher or lower than intended. It’s just that it takes more pressure to move the shift lever than some staffers liked. The tester who owned a DKW five years ago couldn’t understand what the fuss was about—compared to early Sachs gearboxes, everything else shifts great. But riders with more sensitive shifting toes declared the 750 a slightly notchy shifter. Another thought that the problem might lie in the clutch, which doesn’t fully engage until the very end of lever release, but doesn’t completely disengage until the lever is almost to the grip. Thus the clutch could be slightly loading the transmission and making it harder to shift if the rider isn't careful with the clutch lever.

Then, too, there are problems with the anti-emissions carburetor alterations. There is a slight throttle hesitation coming off small throttle openings. Say you’re riding slowly in a mass of backed-up traffic at 3000-3500 rpm in first gear, and want to speed up a bit. Rolling on the throttle yields a momentary glitch of uneven response. Even the smoothest throttle application doesn’t avoid it, and if you pay attention, the problem is still noticeable at about 3500 in fifth gear on the expressway. Perhaps many people won't notice the momentary lean condition described above, (a condition which Honda avoids through the use of accelerator pumps on its 1979 carburetors). But every rider will notice the Suzuki’s obstinate behavior when cold.

Various motorcycles have been referred to in the past as being cold blooded, but the GS750 sets new standards for refusal to run right until the engine is warm. Getting the bike to fire in the morning takes zero throttle and full choke, with at least two minutes of warm-up time before the bike will accept enough throttle to rev past 3000 rpm. More than Vs throttle sends the bike into staggers and fits for even longer, and throttle response doesn’t exist until after several miles of riding. There is a way around the problem—almost—if the rider doesn't mind living with the acceleration of a fully-loaded cement truck for several minutes. The stopgap answer is to leave the choke full on and barely, ever-soslightly crack the throttle, let the clutch out at 3000 rpm and ride off', shifting at about 3500 rpm and keeping more-or-less steady throttle. It won't thrill the pilot, but even moving slowly may be better than not moving at all while waiting for the engine to warm up. The colder the morning, the greater the problem, and the longer it takes to achieve normal throttle response.

Another annoyance comes in the form of the carburetor return spring, which is stiff to the point of causing agony on long rides. No wonder Suzuki incorporated provisions for the addition of a cruise control on 1979 models.

Red instrument lighting debuted with the original GS750 and is still used. One staffer objected to the lighting, saying that he found the traditional green instrument lighting more readable. Others liked the red lighting just fine. The speedometer, tachometer, odometer and resettable tripmeter are all easy to read in the daytime and well-lit at night. The speedometer, as expected, is optimistic, reading 30 mph at an actual 26 mph and indicating 60 mph at an actual 55 mph.

The change from the familiar LED digital gear indicator to five individual bulbs lighting five separate gear numbers (arranged in an arc on the instrument panel) came after every other alternative was tried to make the LED display readable in bright sunlight. Before finally abandoning it this year, Suzuki tried at least four changes in the LED system, including going to brighter LEDs, altering the display angle, and experimenting with different display cover glass shades and densities. Still, bright-sunlight readability just wasn't there, so the new system was developed. It can be read during the daytime.

Lighting front and rear and controls are all good, although the taillight bulb filament burned out on our test bike, very rare for Japanese motorcycles. As is normal these days, the headlight and taillight come on with the engine and stay lit constantly, in theory increasing machine conspicuity, and hence, rider safety.

As good as the lights and controls are. the handlebar grips are horrendous. These rubber disasters are hard, with ridges and bumps seemingly designed to eat through riding gloves and irritate and blister flesh. They’ve been found on Suzukis for years, and are the first thing a rider should junk. In grips, Hondas have street Suzukis beat in every way. The best use for any and all such Suzuki grips would be as shredded filler material in asphalt highways, or perhaps—in recycled form—as boat hull fenders.

New this year is an accessory terminal under a side cover, complete with 10-amp fuse. In theory that makes it easy for a GS750 owner to hook up a CB, stereo tape player, AM/FM radio, radar detector or whatever with the fuse for protection in case of short circuit or overload. But the terminal (which is actually a simple screw) would have been better located in the headlight shell, since most electrical accessories are installed in frame-mount fairings by touring riders.

While styling is a matter of personal taste, we’ve always liked the looks of the GS750 and find the GS750EN even more visually appealing. The only distasteful things on the bike are the tacky-looking joints between the sections of the decal “pinstriping” on the gas tank. The colors and shape of the stripes are fine, but the location of the joints and the amount of overlap call close-range attention to the fact that they are indeed decals applied over the color paint coats and underneath the final clear coats.

In certain maintenance aspects, the GS750 has stayed where it was three years ago while the competition has moved forward. The GS still has breaker point ignition, while the latest Hondas and Yamahas come with maintenance-free pointless electronic ignition systems. Compared to the four-valves-per-cylinder Honda CB750K, however, the two-valves-per-cylinder GS750 has an advantage when it comes time to adjust the valves—fewer valves means less work. The Suzuki also has an automatic cam chain tensioner. The GS750 is very straightforward to maintain, and the official GS750 shop manual is very good, better in fact than the non-factory manuals on the market. Owners who want to adjust their bike’s valves can buy a Suzuki shim kit and special tool to do so.

When it comes to the really big things, the essence of a motorcycle—performance, handling, suspension, braking, rider comfort—the GS750 works. It carries the usual appeal of a 750 compared to a 1000—such as a smaller purchase price, lower insurance premium and a smaller parts bill for tires and chains—yet delivers more power than a 650 or 550 or 500.

It is versatile. One staffer has road raced seven different GS750s in various configurations and displacements, and rode one from Daytona to Los Angeles in 1978. The bike is at home in urban traffic, on super highways and on the banking of a speed bowl.

At its introduction three years ago—a long time in the accelerating technology of our time—the GS750 was revolutionary, a functional pioneer. The others have had those three years to catch up, yet the Suzuki GS750—especially the GS750EN — still stands as the best all around 750 you can buy.

SUZUKI

GS750 EN

$2729