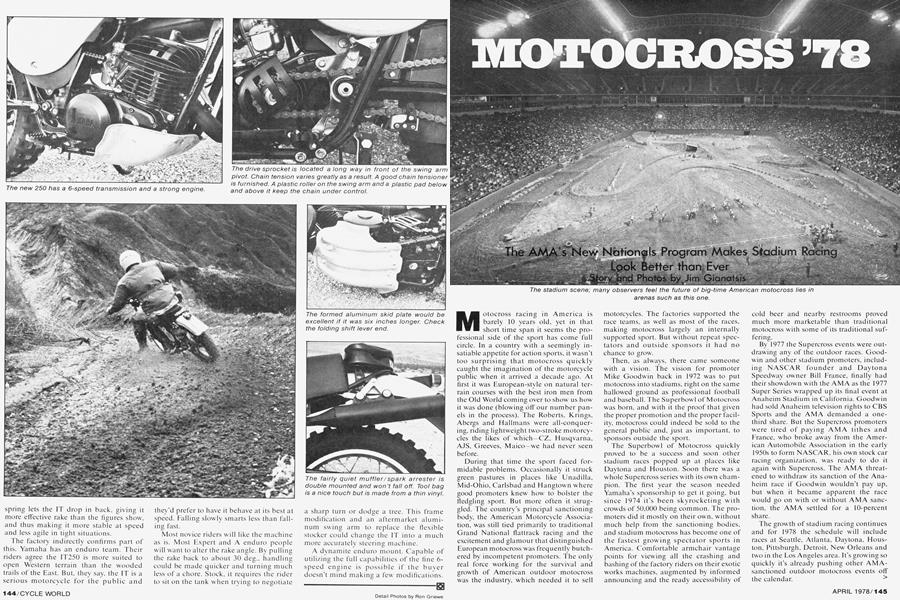

MOTOCROSS'78

The AMA'S New Nationals program Makes Stadium Racing Look Better than Ever

Jim Gianatsis

Motocross racing in America is barely 10 years old, yet in that short time span it seems the professional side of the sport has come full circle. In a country with a seemingly insatiable appetite for action sports, it wasn't too surprising that motocross quickly caught the imagination of the motorcycle public when it arrived a decade ago. At first it was European-style on natural terrain courses with the best iron men from the Old World coming over to show us how it was done (blowing off our number panels in the process). The Roberts, Krings, Abergs and Hallmans were all-conquering, riding lightweight two-stroke motorcycles the likes of which-CZ, Husqvarna, AJS, Greeves, Maico-we had never seen before.

During that time the sport faced for midable problems. Occasionally it struck green pastures in places like Unadilla, Mid-Ohio, Carlsbad and Hangtown where good promoters knew how to bolster the fledgling sport. But more often it strug gled. The country's principal sanctioning body, the American Motorcycle Associa tion, was still tied primarily to traditional Grand National flattrack racing and the excitement and glamour that distinguished European motocross was frequently butch ered by incompetent promoters. The only real force working for the survival and growth of American outdoor motocross was the industry, which needed it to sell motorcycles. The factories supported the race teams, as well as most of the races, making motocross largely an internally supported sport. But without repeat spectators and outside sponsors it had no chance to grow.

Then, as always, there came someone with a vision. The vision for promoter Mike Goodwin back in 1972 was to put motocross into stadiums, right on the same hallowed ground as professional football and baseball. The Superbowl of Motocross was born, and with it the proof that given the proper promotion and the proper facility. motocross could indeed be sold to the general public and, just as important, to sponsors outside the sport.

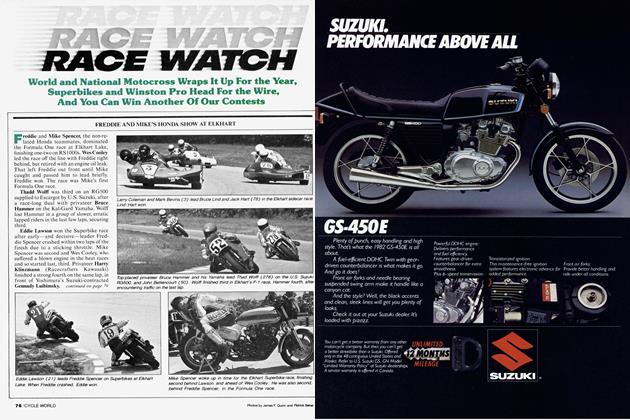

The Superbowl of Motocross quickly proved to be a success and soon other stadium races popped up at places like Daytona and Houston. Soon there was a whole Supercross series with its own champion. The first year the season needed Yamaha's sponsorship to get it going, but since 1974 it's been skyrocketing with crowds of 50,000 being common. The promoters did it mostly on their own, without much help from the sanctioning bodies, and stadium motocross has become one of the fastest growing spectator sports in America. Comfortable armchair vantage points for viewing all the crashing and bashing of the factory riders on their exotic works machines, augmented by informed announcing and the ready accessibility of cold beer and nearby restrooms proved much more marketable than traditional motocross with some of its traditional suffering.

By 1977 the Supercross events were outdrawing any of the outdoor races. Goodwin and other stadium promoters, including NASCAR founder and Daytona Speedway owner Bill France, finally had their showdown with the AMA as the 1977 Super Series wrapped up its final event at Anaheim Stadium in California. Goodwin had sold Anaheim television rights to CBS Sports and the AMA demanded a onethird share. But the Supercross promoters were tired of paying AMA tithes and France, who broke away from the American Automobile Association in the early 1950s to form NASCAR, his own stock car racing organization, was ready to do it again with Supercross. The AMA threatened to withdraw its sanction of the Anaheim race if Goodwin wouldn't pay up, but when it became apparent the race would go on with or without AMA sanction, the AMA settled for a 10-percent share.

The growth of stadium racing continues and for 1978 the schedule will include races at Seattle, Atlanta, Daytona, Houston, Pittsburgh, Detroit, New Orleans and two in the Los Angeles area. It's growing so quickly it's already pushing other AMAsanctioned outdoor motocross events off the calendar.

And what of outdoor motocross? Under uncertain guidance from the AMA, it began to lose its momentum in 1974. The national championships and the TransAMA series stayed alive because the factories supported the races, sending heavily financed race teams to perform before often-slim crowds. U.S. Suzuki kept the Trans-AMA series alive almost singlehandedly, sending six-time world champion Roger DeCoster to contest, and walk away with, our international series each fall since 1974.

The salvation for outdoor motocross in America may lie in the involvement of major non-industry sponsors. In 1977 Goodwin landed Coca-Cola and its Mr. Pibb soft drink as a sponsor of the Atlanta stadium race. After the very successful Atlanta race Goodwin got Mr. Pibb and the AMA together for sponsorship of the 500cc national, the first time since the advent of the AMA 500cc national championship in 1970 that any of the three national championship classes ever had a sponsor.

During 1977 Mr. Pibb kicked in $10,000 to the riders' point fund, mere paper clip money in Coca-Cola's half-billion dollar advertising budget, but at least the groundwork had been set. For the 1978 racing season Mr. Pibb wanted to kick in $10,000 in each of the three national classes— 125cc, 250cc and Open. Local Mr. Pibb bottlers would also help individual race promoters with advertising expenses, and the AMA would coordinate things. It was a dream too good to be true, but the AMA leaders had a problem. They couldn't find enough good promoters.

So the AMA hit upon a grand scheme to revitalize the nationals and draw in new promoters. In the past, the three national championships were divided into a series of five races each, almost all run on separate race dates. There were a few conflicting dates such as the two nationals on the same day at Hangtown. but for the most part everyone could race all of the races. And it made for some damn good racing because all the top factory and privateer riders in the country would be racing in the same class on the same track on the same Sunday. Top riders like Bob Hannah and Marty Smith were good enough to come close to winning a national championship, in two if not three classes, which added to the excitement.

But in order to sell the national championships to promoters, the AMA thought up a great two-for-one bargain sale. Offer every promoter two national classes on the same day at his track and reduce the purse tor each class to $5000. There would still be a total of 15 events, but the total number of races in each class would be raised from five to 10. And because all the classes were being scheduled on the same day as another class, a rider could only opt to ride one national class for the year and he would have to make that selection before the nationals began.

These changes are supposed to help the privateer riders. Since the factories would have to divide their riders among a total of 30 national events, 10 per class, held at 15 different locations, the AMA told the privateers they would be making a lot more money. What they forgot to tell the privateers, though, is that the purses are smaller, and that they have to drive across the country to follow a national class which now consists of 10 races instead of 5.

The real clincher on the deal was when the better-heeled Japanese factory teams began hiring more riders for the 1978 season to fill out the classes where they didn't have riders. Almost everyone began to think this new system for 1978 isn't such a hot idea.

The privateers are going to be hurting because they have to go to more races to compete for less money against just as many factory riders as before. The Japanese factories are hurting because each of them—Yamaha, Honda, Suzuki and Kawasaki—had to spend more money to hire more riders to fill out each of the classes. And it wasn't all privateer riders they hired to fill out their ranks. Some came from the smaller European factory teams like Maico and Husqvarna which couldn't match the big-bucks contracts the Japanese teams had to offer. So the smaller European teams were left hurting.

The new program may penalize spectators as well as riders. Are the spectators going to come out to see only one-third of the best riders in the country racing in a particular class, especially when they can see all the top riders racing together in either the Trans-AMA or Supercross series? And will the racing be any good? With only a few top riders in each class, one or two are sure to dominate and leave the others far behind. Gone will be the exciting duels between Marty Smith and Bob Hannah, Broc Glover and Danny LaPorte, Jimmy Weinert and Steve Stackable.

Only the end of the 1978 national championship season will determine the effectiveness of the AMA's new program. But whether outdoor crowds are up or down, it seems likely that the future of professional motocross in this country lies in the stadiums. IS]