A DIFFERENT TRIUMPH

You Say the Bonneville Weighs Too Much? Well . . .

Chuck Johnston

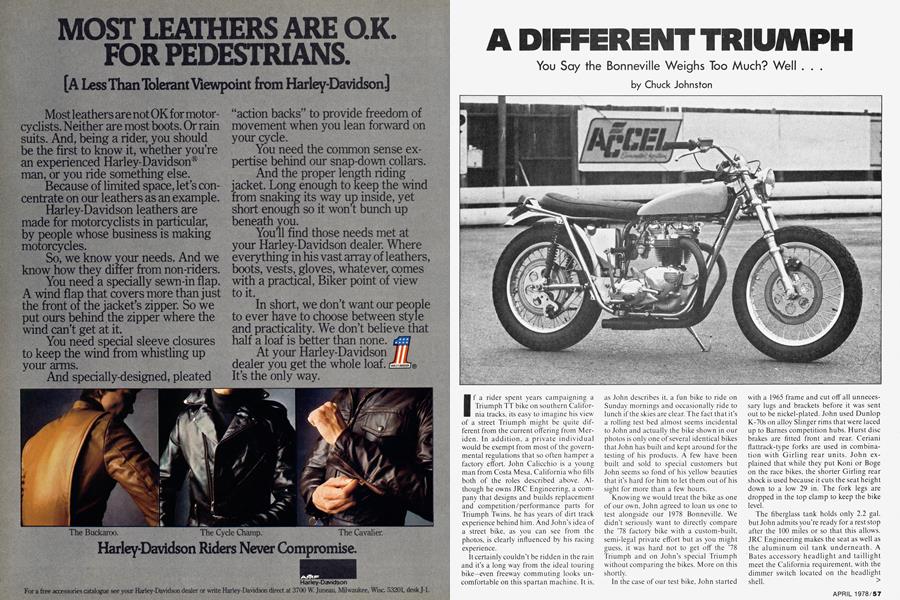

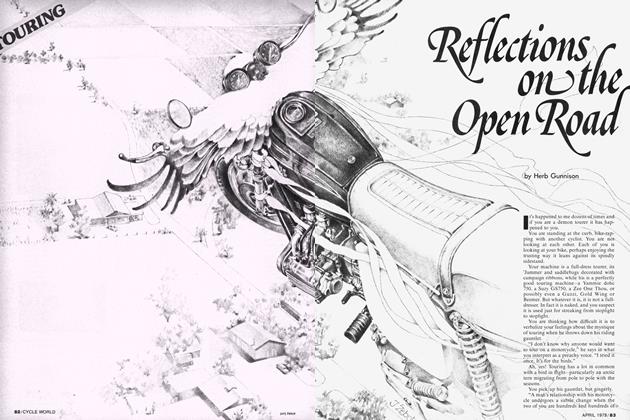

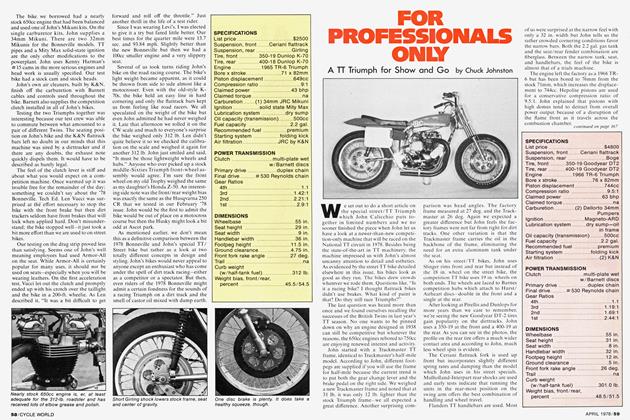

If a rider spent years campaigning a Triumph TT bike on southern California tracks, its easy to imagine his view of a street Triumph might be quite different from the current offering from Meriden. In addition, a private individual would be exempt from most of the governmental regulations that so often hamper a factory effort. John Calicchio is a young man from Costa Mesa, California who fills both of the roles described above. Although he owns JRC Engineering, a company that designs and builds replacement and competition/performance parts for Triumph Twins, he has years of dirt track experience behind him. And John's idea of a street bike, as you can see from the photos, is clearly influenced by his racing experience.

It certainly couldn't be ridden in the rain and it's a long way from the ideal touring bike—even freeway commuting looks uncomfortable on this spartan machine. It is, as John describes it, a fun bike to ride on Sunday mornings and occasionally ride to lunch if the skies are clear. The fact that it's a rolling test bed almost seems incidental to John and actually the bike shown in our photos is only one of several identical bikes that John has built and kept around for the testing of his products. A few have been built and sold to special customers but John seems so fond of his yellow beauties that it's hard for him to let them out of his sight for more than a few hours.

Knowing we would treat the bike as one of our own, John agreed to loan us one to test alongside our 1978 Bonneville. We didn't seriously want to directly compare the '78 factory bike with a custom-built, semi-legal private effort but as you might guess, it was hard not to get off the '78 Triumph and on John's special Triumph without comparing the bikes. More on this shortly.

In the case of our test bike, John started with a 1965 frame and cut off all unnecessary lugs and brackets before it was sent out to be nickel-plated. John used Dunlop K-70s on alloy Slinger rims that were laced up to Barnes competition hubs. Hurst disc brakes are fitted front and rear. Ceriani flattrack-type forks are used in combination with Girling rear units. John explained that while they put Koni or Boge on the race bikes, the shorter Girling rear shock is used because it cuts the seat height down to a low 29 in. The fork legs are dropped in the top clamp to keep the bike level.

The fiberglass tank holds only 2.2 gal. but John admits you're ready for a rest stop after the 100 miles or so that this allows. JRC Engineering makes the seat as well as the aluminum oil tank underneath. A Bates accessory headlight and taillight meet the California requirement, with the dimmer switch located on the headlight shell.

The bike we borrowed had a nearly stock 650cc engine that had been balanced and used one of John's Mikuni kits. On the single carburetor kits, John supplies a 34mm Mikuni. There are two 32mm Mikunis for the Bonneville models. TT pipes and a Mity Max solid-state ignition are the only other modifications to the powerplant. John uses Kenny Harman's # 15 cams in the more serious engines and head work is usually specified. Our test bike had a stock cam and stock heads.

John's own air cleaners, built by K&N, finish off the carburetion with Barnett cables and controls used throughout the bike. Barnett also supplies the competition clutch installed in all of John's bikes.

Testing the two Triumphs together was interesting because our test crew was able to commute between what amounted to a pair of different Twins. The seating position on John's bike and the K&N flattrack bars left no doubt in our minds that this machine was sired by a dirttracker and if there are any doubts, the exhaust note quickly dispels them. It would have to be described as barely legal.

The feel of the clutch lever is stiff and about what you would expect on a competition machine. Once warmed up it was trouble free for the remainder of the day; something we couldn't say about the '78 Bonneville. Tech Ed. Len Vucci was surprised at the effort necessary to stop the bike with the front brake but then dirt trackers seldom have front brakes that will lock when applied hard. Don't misunderstand; the bike stopped well—it just took a bit more effort than we are used to on street bikes.

Our testing on the drag strip proved less than satisfying. Seems one of John's well meaning employees had used Armor-All on the seat. While Armor-All is certainlypopular for many uses, it should not be used on seats—especially when you will be wearing leathers. On the first acceleration test, Vucci let out the clutch and promptly ended up with his crotch over the taillight and the bike in a 200-ft. wheelie. As Len described it, "It was a bit difficult to get forward and roll off the throttle." Just another thrill in the life of a test rider.

Since I was wearing Levi's, I was elected to give it a try but fared little better. Our best times for the quarter mile were 13.7 sec. and 93.84 mph. Slightly better than the new Bonneville but then we had a lOOcc smaller engine and a very slippery seat.

Several of us took turns riding John's bike on the road racing course. The bike's light weight became apparent, as it could be thrown from side to side almost like a motocrosser. Even with the old-style K70s, the bike held an easy line in hard cornering and only the flattrack bars kept us from feeling like road racers. We all speculated on the weight of the bike but even John admitted he had never weighed it. Late that afternoon we rolled it on the CW scale and much to everyone's surprise the bike weighed only 312 lb. Len didn't quite believe it so we checked the calibration on the scale and weighed it again for another 312 lb. John just smiled and said, "It must be those lightweight wheels and hubs." Anyone who ever picked up a stock middle-Sixties Triumph front-wheel assembly would agree. I'm sure the front wheel on my old Trophy weighed the same as my daughter's Honda Z-50. An interesting side note was the front/rear weight bias was exactly the same as the Husqvarna 250 CR that we tested in our February '78 issue. John would be the first to admit the bike would be out of place on a motocross course but then the Husky might look a bit odd at Ascot park.

As mentioned earlier, we don't mean this as a definitive comparison between the 1978 Bonneville and John's special TT/ Street bike but rather as a look at two totally different concepts in design and styling. John's bikes would never appeal to anyone except an enthusiast who has come under the spell of dirt track racing—either as a competitor or a spectator. But then, even riders of the 1978 Bonneville might admit a certain fondness for the sounds of a racing Triumph on a dirt track and the smell of castor oil mixed with damp earth.

$2500