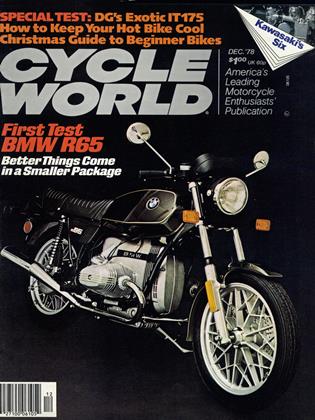

The Fast Go Faster

303 mph Wasn’t Fast Enough For Don Vesco. Now The Speed Record Is 318 mph.

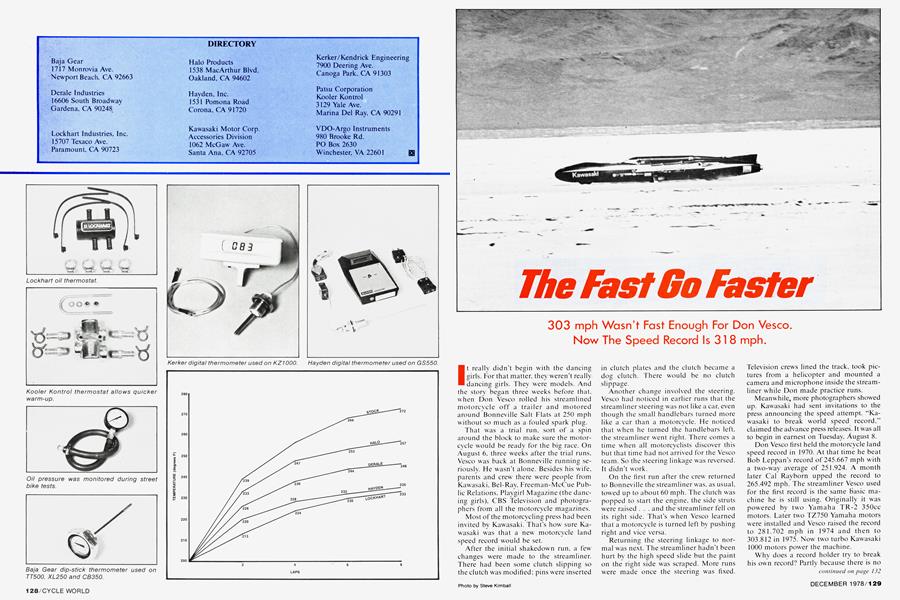

It really didn’t begin with the dancing girls. For that matter, they weren't really dancing girls. They were models. And the story began three weeks before that, when Don Vesco rolled his streamlined motorcycle off a trailer and motored around Bonneville Salt Flats at 250 mph without so much as a fouled spark plug.

That was a trial run, sort of a spin around the block to make sure the motorcycle would be ready for the big race. On August 6. three weeks after the trial runs. Vesco was back at Bonneville running seriously. He wasn’t alone. Besides his wife, parents and crew there were people from Kawasaki. Bel-Ray, Freeman-McCue Public Relations. Playgirl Magazine (the dancing girls). CBS Television and photographers from all the motorcycle magazines.

Most of the motorcycling press had been invited by Kawasaki. That's how sure Kawasaki was that a new motorcycle land speed record would be set.

After the initial shakedown run, a few changes were made to the streamliner. There had been some clutch slipping so the clutch was modified; pins were inserted in clutch plates and the clutch became a dog clutch. There would be no clutch slippage.

Another change involved the steering. Vesco had noticed in earlier runs that the streamliner steering was not like a car, even though the small handlebars turned more like a car than a motorcycle. He noticed that when he turned the handlebars left, the streamliner went right. There comes a time when all motorcyclists discover this but that time had not arrived for the Vesco team. So the steering linkage w’as reversed. It didn’t work.

On the first run after the crew returned to Bonneville the streamliner was, as usual, towed up to about 60 mph. The clutch was popped to start the engine, the side struts were raised . . . and the streamliner fell on its right side. That’s when Vesco learned that a motorcycle is turned left by pushing right and vice versa.

Returning the steering linkage to normal was next. The streamliner hadn't been hurt by the high speed slide but the paint on the right side was scraped. More runs w^ere made once the steering was fixed.

Television crews lined the track, took pictures from a helicopter and mounted a camera and microphone inside the streamliner while Don made practice runs.

Meanwhile, more photographers showed up. Kawasaki had sent invitations to the press announcing the speed attempt. “Kawasaki to break world speed record.” claimed the advance press releases. It was all to begin in earnest on Tuesday, August 8.

Don Vesco first held the motorcycle land speed record in 1970. At that time he beat Bob Leppan’s record of 245.667 mph with a two-way average of 251.924. A month later Cal Rayborn upped the record to 265.492 mph. The streamliner Vesco used for the first record is the same basic machine he is still using. Originally it w'as powered by two Yamaha TR-2 350cc motors. Later two TZ750 Yamaha motors were installed and Vesco raised the record to 281.702 mph in 1974 and then to 303.812 in 1975. Now two turbo Kawasaki 1000 motors power the machine.

Why does a record holder try to break his own record? Partly because there is no other competition. There’s only one absolute motorcycle speed record, regardless of who holds it. Vesco is obviously in a class by himself because no one else is competing. But the real reason he races is because he likes to do it.

continued on page 132

continued from page 129

When all the reporters and photographers and models and everyone else arrived. the Vesco team was set. The air was calm at sunrise that Tuesday, just as it has to be to qualify for a world record. No more than a 5 mph wind is allowed by the rules. By the time the spark plugs were changed, tires pumped up to 100 psi. nitrogen bottle filled and all the other preparations complete it was 8 a.m. A slight breeze occasionally blew' across the 11 miles of graded salt the streamliner would streak across. The streamliner w'as hauled to the end of the course, Don was carefully belted in place and the first serious run began.

Before the streamliner w:as towed a quarter of a mile its engines were started, the tow cord was disconnected and the acceleration began. At the speeds the cycle was designed for. a trip across the salt flats could be made in as little as tw'o minutes. A little more than two minutes after the trip began, it ended. The streamliner braked to a halt near the three mile marker. No record was set: it jammed in third gear and only went 270 mph. By the time the shift linkage had been repaired and a minor clutch problem fixed the wind had increased too much for another run. Everybody waited.

There was a certain amount of enthusiasm generated by the run. Even in third gear Vesco went faster than anyone else has on two wheels. The problems were minor and easily fixed. But there was work to be done during the wait. Important work. One of the sponsors of the Vesco team is Lightning Bolt clothing. That explains why the streamliner had been repainted in dark blue with a bright lightning bolt along each side. That also explains the models.

After the first run the streamliner was pushed off the course with its one stillshining side toward the sun. Fashion pho tographers lined up the Vesco crew and the models behind the streamliner and took pictures of the victory celebration. The pictures were intended for a fashion sec tion of Playgirl Magazine but have since been used in Kawasaki's victory advertis ing. The victory celebration pictures were taken nearly three weeks before the vic tory. That's confidence.

Stronger winds prevented any more runs Tuesday. The crew waited beside the Vesco bus under a flapping tarp in the 90 degree F heat. The next run was Wednesday morning. Vesco turned up the boost on the two turbochargers feeding the twin Ka wasaki 1000 motors. But the first run was aborted. For two miles the rear tire spun down the track before something broke. At first Don thought the transmission had stuck again but when the shell was pulled off the streamliner, one of the two drive belts connecting the two motors fell out and the other had lost its teeth.

Assuming the heat inside the engine compartment was causing a belt problem. the crew cut holes in the aluminum body work and made scoops to cool the belts. Exhaust temperatures from the turbo Ka wasakis were 1200 degrees F, twice as high as the exhaust temperatures of the two stroke Yamaha engines had been. No one knew how hot the engine compartment was.

A third run was made, without the bot tom panel under the engines. Again the belts broke. The belts that broke were new. improved belts, supposedly stronger than the belts used with the Yamaha motors. But the turbo Kawasaki produced about twice the power of the motors and, being four-stroke motors, also produced twice the impact of a two-stroke.

For the fourth run the original belts used on the Yamahas were installed, deflector panels to keep salt from hitting the belts were fabricated and the rear tire and turbo were replaced. It was late afternoon when the team was ready for a fourth run. Before running, though, the streamliner was pushed onto the start-up rollers for a prerun check. But the motors didn’t want to start in first gear. Occasionally first gear would crank the motors but at times it wouldn’t. First gear was gone. A decision was made to run without first gear so the streamliner was shifted into second. Only the Kaw'asaki KL250 pit bike used to power the rollers couldn’t spin the engines fast enough in second. A 400cc Suzuki tried but it couldn’t match the KL’s performance.

Only one other motorcycle was available at the starting line, the CYCLE WORLD test Gold Wing. Kawasaki public relations men shuddered as the Honda rolled up beside the Kawasaki streamliner. It felt good to be doing something constructive instead of just taking pictures, and the test Honda easily spun over the sausage-shaped racer’s motors.

The check was finished and the run began. Another problem. This time a chain broke w'hen Vesco popped the clutch while being towed. Another chain was quickly installed and a fifth run tried. It broke. The teeth from the first gear were bouncing into the transmission, causing the transmission to lock and the chain to break w hen the clutch was popped.

Although the gears used were a special set of close ratio cogs, the single transmission was entirely stock. Only the rear motor had a transmission, with power transferred from the front engine to the rear engine with toothed belts connecting the ends of the two crankshafts. That means the crank of the rear engine and the transmission were transmitting up to 400 bhp. four times what they were designed to handle.

With considerable work to be done, the spectators left. Part of the Vesco crew' had to return to regular jobs, photographers and reporters had to return to magazines and only a few' people remained to work. The rear motor was removed and stock gears installed. The base plate was cut and spliced together, stretching the two motors apart to prevent the belts from being shredded.

By the time Don finished repairing the streamliner, the weather had soured: it was> raining. When the rain quit, the wind blew'. Occasionally during the following two weeks the wind would die. a run would be made and a gearbox would break. Five gearboxes were used during the series of runs. A specially hardened set of drag race gears was sent in from Chicago. It broke. A new clutch had to be fabricated; the parts used were a snap ring, chisel and file. “It’s trick,” said Don. Gradually the bugs were worked out. A new' technique for getting on the pow-er was devised.

Don stretched a piece of rubber hose from the screw which controls turbo boost pressure to the handlebars. Because the straps which hold him into the streamliner prevent him from reaching anything but the grips, it was the only way he could control boost pressure while driving. Boost control, in effect, became the throttle.

Finally on Friday, August 25, starting out with little boost and only turning up the screw when the bike was in 5th gear, a successful run was made, down and back for a new' motorcycle land speed record of 314.286. Everything worked. When another run was started the belts, the same belts used on the original Yamaha 750 motors and used for the last two weeks, finally broke. But Kawasaki had the record.

New belts were ordered and television camera crews were brought back for another record run the following Monday. On the first run the streamliner entered the timing lights at 314.286 mph and left at 322.696 for an average one way speed of 318.330. Like most of the earlier, aborted runs the first run began at Mile 11 where the salt was better for acceleration. On the return run the batteries for the timing lights were running down and only the overall speed was recorded; 318.866 mph. The average speed, the new' w'orld record, became 318.598. Vesco’s three-year-old record of 303.812 had been raised by nearly 15 mph.

Finally, everything worked. There was never a shortage of power. The problems had been harnessing the power. Now the system worked. Obviously the streamliner could go faster. Somehow.

With a new absolute motorcycle speed record, Kawasaki got what it paid for: a reinforced image as the fastest motorcycle. Vesco also got what he needed: support from Kawasaki for building a new streamliner. The 11-year-old cycle isn’t finished yet, though. For Bonneville Speed Week a larger rear tire and higher gearing will be mounted and Vesco will try for a one-way speed record of 350 mph. And that’s only a beginning.

A new' streamliner is being designed now'. It will probably look similar to the present machine but it will be bigger, housing three Kawasaki six-cylinder motors hooked together with a shaft and driving a Hewland gearbox. That streamliner will be designed for speeds of 400 mph—fast enough to be the fastest wheeldriven land vehicle, regardless of number of wheels.

Next year it will be ready. All of this year’s efforts will be the foundation just as the speed record of 1975 was the foundation for this year’s run. S)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsThe Wider You Spread It, the Thinner It Gets

DECEMBER 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

DECEMBER 1978 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

DECEMBER 1978 -

The All-Thumbs Tool Kit

DECEMBER 1978 By Don Norris -

Competition

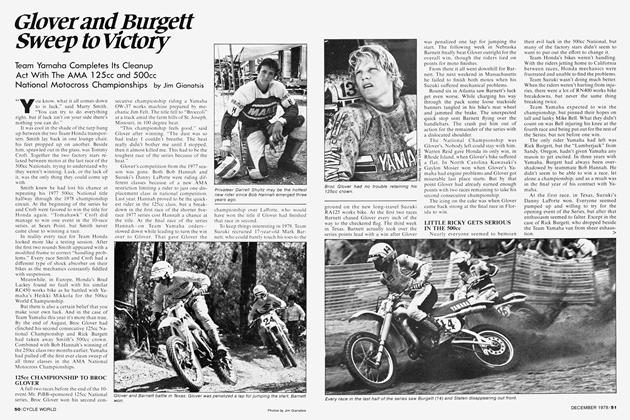

CompetitionGlover And Burgett Sweep To Victory

DECEMBER 1978 By Jim Gianatsis -

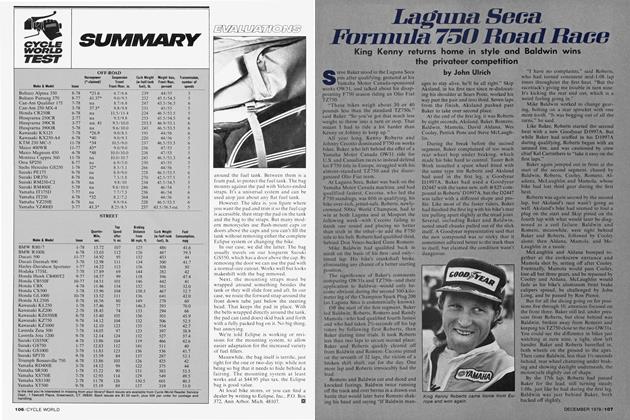

Cycle World Test

Cycle World TestSummary

DECEMBER 1978