STARS ON TRIAL

Mike Obermeyer

Port Huron begins as a surprise, a small northern Michigan town that looks like the set of a 1950s movie. The country is farmland, contoured and cultivated. At first glance Port Huron and surroundings doesn't seem to be the right locale for the U.S. round of the F.I.M. world trials championship.

Follow the signs into the woods and the wisdom of the host club, the MichiganOntario Trials Assn., becomes proven. There they are, by God. actual rock-lined gullies to ride in.

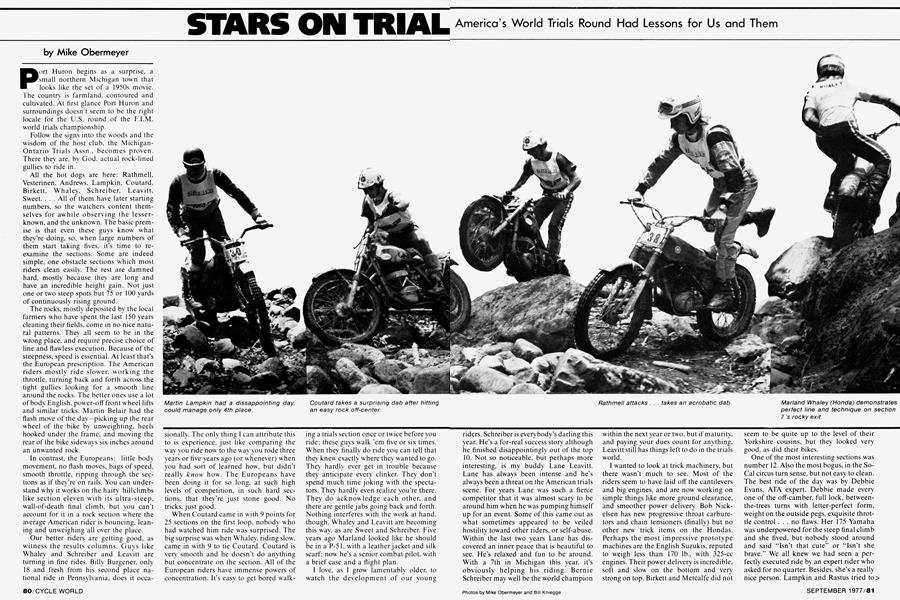

All the hot dogs are here: Rathmell. Vesterinen, Andrews, Lampkin, Coutard, Birkett, Whaley, Schreiber, Leavitt, Sweet. . . . All of them have later starting numbers, so the watchers content themselves for awhile observing the lesserknown, and the unknown. The basic premise is that even these guys know what they’re doing, so, when large numbers of them start taking fives, it’s time to reexamine the sections. Some are indeed simple, one obstacle sections which most riders clean easily. The rest are damned hard, mostly because they are long and have an incredible height gain. Not just one or two steep spots but 75 or 100 yards of continuously rising ground.

The rocks, mostly deposited by the local farmers who have spent the last 150 years cleaning their fields, come in no nice natural patterns. They all seem to be in the wrong place, and require precise choice of line and flawless execution. Because of the steepness, speed is essential. At least that’s the European prescription. The American riders mostly ride slower, working the throttle, turning back and forth across the tight gullies looking for a smooth line around the rocks. The better ones use a lot of body English, power-off front wheel lifts and similar tricks. Martin Belair had the flash move of the day—picking up the rear wheel of the bike by unweighting, heels hooked under the frame, and moving the rear of the bike sideways six inches around an unwanted rock.

In contrast, the Europeans: little body movement, no flash moves, bags of speed, smooth throttle, ripping through the sections as if they’re on rails. You can understand why it works on the hairy hillclimbs like section eleven with its ultra-steep, wall-of-death final climb, but you can’t account for it in a rock section where the average American rider is bouncing, leaning and unweighing all over the place.

Our better riders are getting good, as witness the results columns. Guys like Whaley and Schreiber and Leavitt are turning in fine rides. Billy Burgener, only 18 and fresh from his second place national ride in Pennsylvania, does it occasionally. The only thing I can attribute this to is experience, just like comparing the way you ride now to the way you rode three years or five years ago (or whenever) when you had sort of learned how, but didn’t really know how. The Europeans have been doing it for so long, at such high levels of competition, in such hard sections, that they’re just stone good. No tricks, just good.

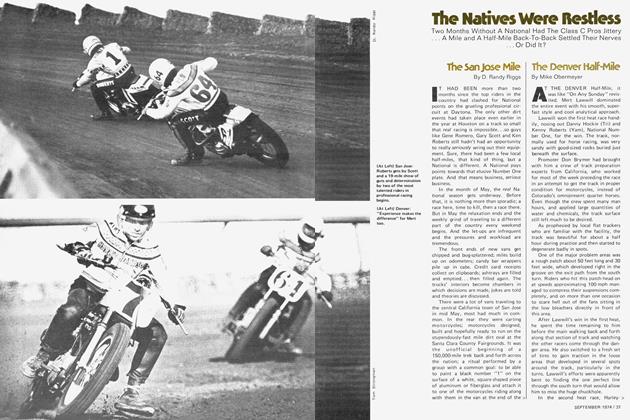

When Coutard came in with 9 points for 25 sections on the first loop, nobody who had watched him ride was surprised. The big surprise was when Whaley, riding slow, came in with 9 to tie Coutard. Coutard is very smooth and he doesn't do anything but concentrate on the section. All of the European riders have immense powers of concentration. It’s easy to get bored walking a trials section once or twice before you ride: these guys walk ’em five or six times. When they finally do ride you can tell that they knew exactly where they wanted to go. They hardly ever get in trouble because they anticipate every clinker. They don’t spend much time joking with the spectators. They hardly even realize you’re there. They do acknowledge each other, and there are gentle jabs going back and forth. Nothing interferes with the work at hand, though. Whaley and Leavitt are becoming this way, as are Sweet and Schreiber. Five years ago Marland looked like he should be in a P-51, with a leather jacket and silk scarf; now he’s a senior combat pilot, with a brief case and a flight plan.

I love, as I grow lamentably older, to watch the development of our young riders. Schreiber is everybody's darling this year. He's a for-real success story although he finished disappointingly out of the top 10. Not so noticeable, but perhaps more interesting, is my buddy Lane Leavitt. Lane has always been intense and he's always been a threat on the American trials scene. For years Lane was such a fierce competitor that it was almost scary to be around him when he was pumping himself up for an event. Some of this came out as what sometimes appeared to be veiled hostility toward other riders, or self-abuse. Within the last two years Lane has dis covered an inner peace that is beautiful to see. He's relaxed and fun to be around. With a 7th in Michigan this year, it's obviously helping his riding. Bernie Schreiber may well be the world champion

America's World Trials Round Had Lessons for Us and Them

within the next year or two, but if maturity, and paying your dues count for anything, Leavitt still has things left to do in the trials world.

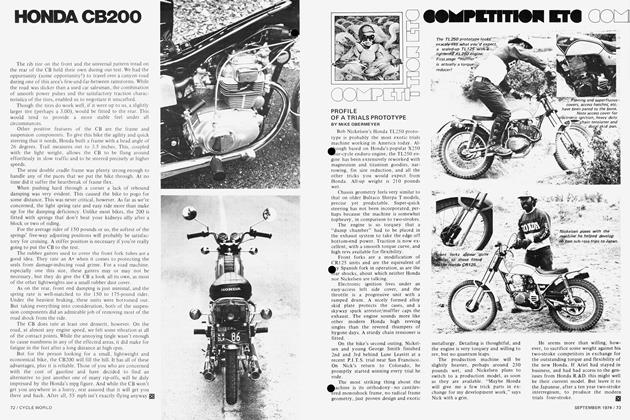

I wanted to look at trick machinery, but there wasn’t much to see. Most of the riders seem to have laid off the cantilevers and big engines, and are now working on simple things like more ground clearance, and smoother power delivery. Bob Nickelsen has new progressive throat carburetors and chain tensioners (finally) but no other new trick items on the Hondas. Perhaps the most impressive prototype machines are the English Suzukis, reputed to weigh less than 170 lb., with 325-cc engines. Their power delivery is incredible, soft and slow on the bottom and very strong on top. Birkett and Metcalfe did not

seem to be quite up to the level of their Yorkshire cousins, but they looked very good, as did their bikes.

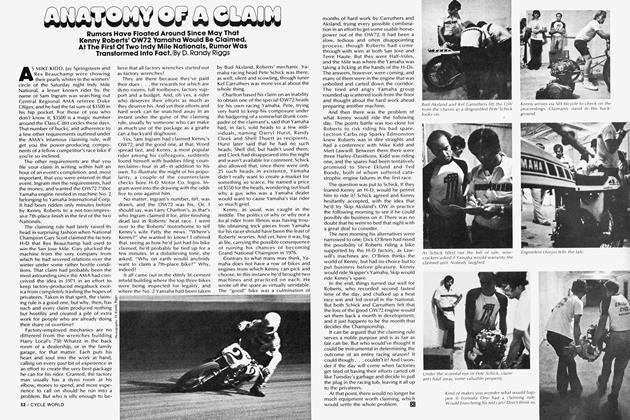

One of the most interesting sections was number 12. Also the most bogus, in the SoCal circus turn sense, but not easy to clean. The best ride of the day was by Debbie Evans, ATA expert. Debbie made every one of the off-camber, full lock, betweenthe-trees turns with letter-perfect form, weight on the outside pegs, exquisite throttle control ... no flaws. Her 175 Yamaha was underpowered for the steep final climb and she fived, but nobody stood around and said “Isn’t that cute” or “Isn’t she brave.” We all knew we had seen a perfectly executed ride by an expert rider who asked for no quarter. Besides, she’s a really nice person. Lampkin and Rastus tried to> con her into putting on her now famous headstand routine before the trial, but she refused to bite. She was serious about the event and it showed. Debbie finished well out the the money but showed promise.

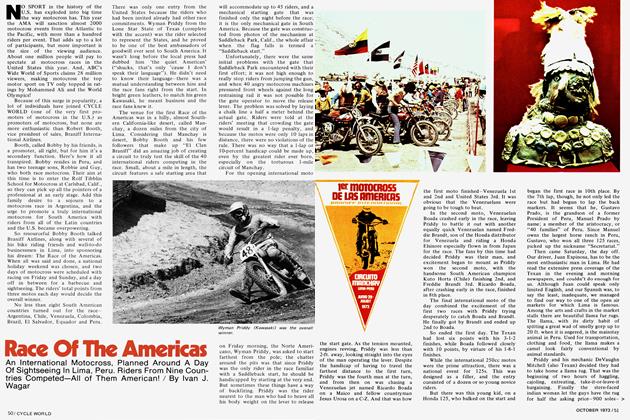

(1) Although reported as disqualified, the AMA advises that Al Eames hand-carried Mike's FIM license to Michigan. Only time, and the FIM will tell. (2) Eggar's ride may count only for international, and not NATC points because of a sign-up error. (3) Current World Champion.

Vesterinen’s second ride on 12 was an interesting contrast to the So-Cal/American style, as exemplified by Debbie Evans. Instead of using outside weight shift to go around the turns, Vesterinen pulled in his clutch and used both brakes to stabilize himself at the difficult downhill to uphill transition point, then dumped the clutch and skidded the turn, weight slightly inside, in a beautiful, controlled slide. I don’t know which way is right, but it was definitely most enlightening.

Most of the Europeans are now riding with the balls of their feet on the pegs, as opposed to riding on their arches. Many of our top riders are switching over to this technique. The theory (or rationale) is that it’s like dancing the ballet on your toes, instead of stumping around on your heels. Nickelsen swears you can’t get into the top 10 in Southern California unless you do it, but nobody seems to completely understand it yet. Bob and I hope to have a supplementary Trials Notebook article on it in the near future, if interest warrants. Speaking of Nickelsen, he won the Senior Class in Michigan, beating Wiltz Wagner and Curt Comer, Sr., and now leads the Senior National Series, ahead of the same two riders.

When the dust settled, super serious Charles Coutard, the young Frenchman who never smiles and has more natural dignity than any six other guys on the tour, had pulled away from Marland by 8.4 points, counting time penalties, and had also pulled off the win in clear and convincing style. Whaley and Schrieber had demonstrated that their European performances were not flukes. Leavitt’s performance was also excellent, and many other Americans showed that they can handle world-class competition. I keep thinking back to a few years ago, when Pomeroy took the first GP ever won by an American. I think we’re on the verge of seeing it happen in trials. I sincerely believe we could have an American World Champion within three years.

Every exposure to the Europeans is instructive, both for the spectator and the competitor. At many of the sections European riders could be seen watching our best riders. The tables seem to be equalizing, if not yet turning. For years now the top Europeans have been coming over here for brief visits. With what occasionally seemed like condescension, they have instructed (and dazzled) our young folk. They may well be regretting that already. Both Marland and Bernie have placed second in world championship events. Bernie has the top finish ever of an American in the Scottish.

Hang on to your hat and root for our troops. We won’t make it this year, but ’78 could be it.