A Professional Look at Motorcycle Accidents,from the Motorcyclist's Viewpoint

When the U.S. Department of Transportation decided a complete motorcycle accident research project was needed, the outline was roughly this: Investigate every motorcycle accident with injury for a given time in a given area. Determine what happens and to whom and why, in order that the various safety groups can figure out how to reduces motorcycle accidents and lessen the injuries that do (and will) occur.

Sounds simple until a glance at the forms for each investigation show 429 facts to be collected per crash.

The assignment went to the University of Southern California’s Institute of Traffic Safety and Systems Management. The institute’s first step was to recruit investigators who also ride motorcycles, on the grounds that unless you know bikes, you won’t know what to look for in a motorcycle crash.

Principal investigator Hugh H. Hurt, Jr. says the team was found quickly except for the required physician. “You don’t see many physicians who ride motorcycles. We did find one who was so interested in the project that she was willing to learn how to ride.”

Describing the actual work as painstaking isn’t enough.

Each report begins with a radio call over the police and emergency monitor. The survey team goes to the site and measures everything. They interview the rider, the passenger, if there is one, and the people in the other vehicle, if one was involved. They go to the hospital for medical reports and more interviews. They talk to the family, to spectators, anybody who may have something to contribute. The next day, or when weather and time conditions duplicate those of the accident, they go back to the scene and flag down bikes.

They learn first what rider crashed where on what. The second check is to see what bikers ride in that place at that time; was this accident a fluke? Or is there a hazard in the street? Still later, the make and model are fed into the computer, to be checked against registration figures in the area. If Henderson Fours have five percent of the crashes and are five percent of the motorcycle population, that means one thing. If every Henderson Four in the area falls over crossing railroad tracks, that’s something else.

One of the report forms ends with the question, “Does the rider have a tattoo?” Odd question, except that psychological studies indicate people with tattoos take more risks than people without them. Given the percentage of the general population with decorations, we can compare that with the percentage of motorcycle riders with a tattoo, and with crashed riders with tattoos, and we’ll have some indication of what part risk-taking plays in bike accidents. (Very little, so far.)

All this is very well and all this is something of a preliminary report. The study isn’t complete, so the conclusions aren’t final.

There are keen trends turning up, though, some of which may save a life, or even allow many riders to feel safer, or vow to improve, or both.

There are all manner of accidents; solo, two bikes, bike vs. car or truck. The median accident, though, one in which any of us could be involved, is almost classic:

The motorcycle is proceeding down the road at the legal speed when an oncoming car turns into the bike’s path and the bike hits it. The rider is hurt, the driver isn’t. The driver didn’t see the motorcycle.

In 80 percent of these accidents, the car was at fault.

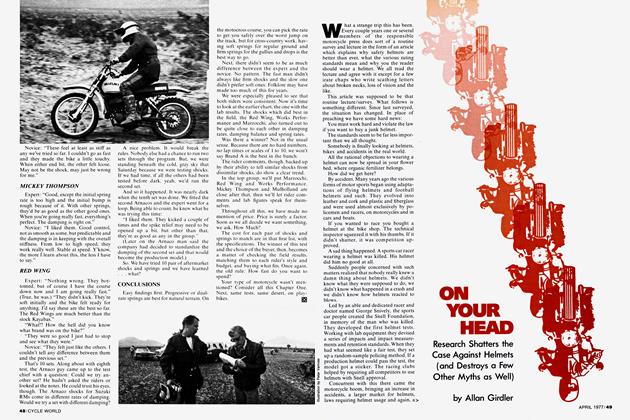

Even so, as mentioned earlier, bareheaded riders are more likely to crash than are riders with helmets.

Hurt says his survey shows 25 percent of the street riders in the Los Angeles area have dirt-riding experience. But so few of these riders are involved with serious crashes that they don’t show up on the statistics.

A large minority of street motorcyclists ride to and from work. But they aren’t hurt in accidents.

Touring is a big part of motorcycling, but riders on long trips don’t get hurt, even when riding through town.

This begins to sound like a contradiction. If most of the time the rider is an innocent victim, then surely all types of riders should be getting knocked off their bikes. There is no contradiction. All types of cyclists are getting turned in front of. Some avoid the accident and some don’t.

Take one typical case. A man on a 750 with disc front brakes is riding along when a car turns into his path. He skids into the side of the car, somersaults over it and lands on the other side, with only minor scrapes.

The USC team found 110 feet of skid marks and worked out that when the car loomed, the bike was doing 42 mph. Later tests showed that that model bike could be stopped from that speed on that street 25 feet away from the car.

You got it. Stupid drivers don’t see motorcycles. They turn into our paths regardless of whether we are experienced riders or not, whether we know how to use the brakes or not.

The rider who is used to reacting quickly, who knows how to swerve and how to brake, doesn’t crash. He stops or avoids the car, shakes his fist and rides away. There is no accident-with-injury to report.

One final preliminary word. The investigators ask every bare-headed rider how he feels about helmets. About 90 percent of them reply they are in favor of helmets, wear them on long trips and such. It just happened that this trip, just down to the store or over to a buddy’s house, they didn’t figure the helmet was that important.

End of lecture. ©