ROAD RIDING

DAN HUNT

FAST COUNTRY RIDING

When you take racing theory away from the race track and apply it to riding on real, imperfect roads for pleasure, many principles have to be compromised. One thing you shouldn’t be doing is going as fast as your bike can stand.

When you race on a race track, you’ve seen it all hundreds of laps before. People in white pants and red jackets are out there manicuring that piece of pavement so that it remains safe. Even if Reginald Van Slied drops his Turbo-Thruster Three on turn two and leaves goo all over the track, chances are you’ll see the danger flag displayed before you get there.

On a road, a real road out in the real world, you haven’t seen it before—no matter how many times you’ve practiced the same run. I used to regularly test the Mulholland road-freak’s milk run from Topanga Canyon all the way up to Camarillo. The road was secure in the morning and at noon. I’d come back about four in the afternoon on the same course and it would be slick as ice. New rock falls would make the practice of shooting blind turns sure confusion if not disaster.

The way you arrange your line for the most efficient way to negotiate turns takes some changing, too. Roadways are not like road circuits. They have traffic going the wrong way. They are not scoured or manicured for the big race.. They have paint on them in the most awkward place, down the middle. They do not have course marshalls at the outside of a blind turn or at the top of a rise (those poor, bored free-time dudes whose apathetic stares mean that: 1) The race is more than halfway over and boy are they getting strung out; 2) The lead is no longer a contest; 3) Nobody has piled up loud enough to get my attention and boy am I bored).

Even when you want to make like a racer out in the countryside, you have to accept the fact that you’ll rarely be riding to the full extent of the capability of yourself and your machine. Races under controlled closed circuit conditions are won when the rider is going at 9/10ths or 10/10ths of his ability. For the sake of the motorcycle, longer races are more often won at 9/10ths, and sometimes the effort is eased to 8/10ths.

(Continued on page 72)

But it is remarkable how fast you can travel over a long distance going 7/10ths. The fraction expressed here is an abstract one, of course, which cannot be measured exactly. But 7/10ths connotes to me a smooth, consistent pressure to go fast that leaves enough leeway for unexpected hazards—the car coming the opposite way just over the white line, the rock that appears around a blind turn right in your chosen line of travel, the country boulevard stop for which there was no warning around the preceding corner, the startled deer that charges down the hillside and across the road in front of you, the motorhome driver who parked his vehicle blocking the single lane around a blind turn in order to admire the view, the recently bladed landslide that left a slippery half-inch patina of sand on the pavement, the dark tree-shadowed canyon that disguises a 20-foot-long patch of water condensation.

Such is the philosophy of 7/10ths. Fast enough to keep you interested. But not so fast that every corner is a 100-percent commitment that cannot be revoked when trouble arrives.

The public highway, no matter how well engineered it may be, no matter how lonely it is, no matter how enticing its solitary beauty as it curves through unexplored countryside, is a ribbon of constant change. You can assume that it will change with every curve. And each change requires your studied, intelligent response.

Most roadways have a line painted down the middle, and some have lines that mark the sides. These lines are both useful and treacherous. They are useful because they set limits of travel for both you and the oncoming traffic. When you can’t see your way out of the turn, the center line should be used as the absolute limit against which to plan the line you’ll take.

The above advice may seem obvious, but it’s easy to forget what is involved. Let’s suppose that you are traveling a blind lefthander at 55 mph. Coming the other way is a car moving at a relatively slow 35 mph. The closing speed is therefore 90 mph. You and the other vehicle close at 132 feet per second. You see him and it takes you a brief quarter-second, you’ve lifted your machine to avoid the intruder: another 33 feet. Subtract another several feet if both you and he are hanging across the center line. The closing distance consumed is about 1/3 the length of a football field, all in a fraction of a second. It is not much time to correct your error or the transgressions of somebody you don’t even know and who may have no reflexes at all. That’s why the yellow line should be inviolate in a blind turn. It’s an unspoken rule in your private little game of play racing.

A wet roadway center line can be treacherous. Even in dry weather, moisture may find its way to that nicely painted, non-absorbent center line. Paint, at the limit of traction, offers less grip than relatively porous road surfaces. But when the paint is the least bit damp, it becomes extremely slick and offers almost no grip at all. Add a small coating of grease from the emissions of passing cars, and it’s murder. You must therefore modify your line. Whenever the bike is to come in contact with that line, you should plan your trajectory so that the bike is fairly vertical. In some parts of the country, the center line is augmented with reflective metal “Cat’s Eyes” planted in the roadway every few feet. Whenever these are the least bit damp or greasy, they promise immediate loss of traction, even at moderate angles of bank.

There is also another “line” on the road that offers trouble. The sweating, dripping oil sumps of automobiles create this foot-wide line more or less in the center of the lane. It may be almost invisible until moisture, either from rainfall, fog, or condensation hits it. When it is freshly wet, oil-soaked pavement is a zero-traction area for a fastmoving bike. You’ll find the heaviest deposits of oil and grease at intersections, where you can set off from a stoplight on a muggy, damp day at your normal rate and immediately provoke wheelspin. Greasy intersections are also likely spots for front wheel washouts as you brake to stop. At busy intersections where stopped cars back up, the danger zone backs up for 50 to 100 feet. That’s why it makes good sense to come to intersections slightly offset from the center of the lane, away from the oil slicks.

Out in the country, oil slicks cause the most trouble when they are laid on well-worn, rough but shiny old asphalt. Fortunately, the biggest deposits are found on sections of country road going uphill, due to the fact that automobiles have to work harder to climb hills, and thus sweat more. In the downhill lane, oil deposits are at a minimum, so they aren’t as great a threat to braking. In all cases, you should plan your line so that maximum stress banking, braking and acceleration do not take place on these areas. When in doubt, offset your bike away from the center of the lane.

(Continued on page 74)

In the case of both paint lines and oil streaks, their relative safety for the biker depends much on the humidity present on both the ground and in the air. When it rains, you obviously slow down, make your riding as smooth as possible and ease your braking and banking forces. If it continues to rain, however, opposite things happen to the paint lines and the oil. The first 20 minutes of a rainstorm are the worst. The oil rises to the surface and becomes a slippery emulsion because of the water. Trouble. But, as the rain becomes heavier, the water will wash the roadway clean of oil, and traction can become very nearly normal if the road material is porous enough.

Paint is not porous, and still constitutes a hazard every time you touch the center line, no matter how long it has rained. If you hit either oil or grease and the bike begins to slip, don’t try to get it back on course immediately. Let the bike have its head, cross the line to regain traction, slow down and recross (if you have to recross) with the machine as straight up as possible, using neither the brakes nor sudden jerks of the throttle. If you enter a turn too hot, lift the bike immediately and stop or slow in a straight line, cutting diagonally to the outer edge of the road. If you leave the road for the soft stuff, get your weight back and rely more on your back brake than your front.

Smoothness in rain riding is important, no matter how well-washed and firm the surface seems to be. Hotdogging the gas, or a sloppy downshift that causes the drive train to jerk, can break the back wheel lose very quickly.

You can make time in the rain, if you watch for the paint lines, the oil, and allow your riding technique to flow like water. Be watchful of good road surface that suddenly becomes shiny with the smoothness of age and the many tires that have buffed it over. You can also spot oil slicks that have not completely washed away by watching for rainbow-hued swirls reflected off a backlit stretch of pavement.

Marginal conditions of moisture can be more dangerous to the rider than a real rainfall, because the water doesn’t announce its presence. But there are ways of predicting these conditions.

If there is, for instance, a ground fog, particularly one that is being pushed along slowly by the wind, you can be sure that water droplets are condensing on an overhanging bridge or tree and falling to the road. Another signal of possible condensation that can grow on either painted lines or oil slicks comes as you ride along in seemingly clear weather. You feel moisture condensing on your face or where your helmet liner touches your cheeks and forehead. Be wary of road conditions ahead whenever you’ve been riding along in dry, warm mountain air and suddenly the temperature drops and your body begins to feel clammy with humidity.

When you ride in the hills, you may generally expect condensation on the windward side of the hill. This is caused by the cooling of moist air as it is lifted by the terrain. As the wind passes to the leeward side of the hill, it drops to a lower level, begins compressing as it gets lower and therefore becomes warmer, absorbing moisture. Thus it may be relatively dry on the leeward side of a hill or mountain.

Whenever you’re riding a coastal range with wind coming from offshore, your greatest caution will be needed climbing or descending on the coastal side, while the leeward side will be driest. Inland, marginal humidity is least likely to occur if you sense that the wind is blowing downhill, but is a possible threat if the wind blows uphill, particularly off a lake or dam. The extent to which this condensation can occur is shocking, but you need only to ride the Coast Highway of California’s Big Sur or the Ortega Highway from San Juan Capistrano to Lake Elsinore to be convinced. Heading inland up the winding Ortega, you can be zipping quickly along in clear, 75-degree weather, slash through a sweeper into a dark area covered by trees and find your tires spraying water—water that has no reason for being there.

Fallen rocks, sand and mud slides can really put a damper on the unwary bike jockey. Obviously you cannot tell whether one of these hazards is around the next corner unless you’ve been there earlier in the day. But you can react to the terrain around you and think a little about the probabilities of such a hazard being nigh.

I use one simple rule: If you pass a rock slide, sand deposit or mud slide on the roadway, chances are that there’s another one coming up soon. In the mountains, it’s hard to see around corners, but you sometimes can see the terrain ahead and above. If you spot erosion slashes in a rocky, barren bank, or a channel that looks like a natural drainoff from the hillside that intersects your road farther on down the line, good sense will tell you to cool it when you can’t see the far side of the curve. Rocks and mud tend to arrive on the road in a seasonal manner, usually following a rainy spell. If you live in the area, you should crank these seasonal tendencies through your estimates of what lies ahead on your favorite practice course. In the days when I was polishing my skills twice weekly in the Malibu mountains near my home, I developed the habit of watching for the fresh marks of a bulldozer or streetsweeper; this meant that the landslide season was in full bloom and a blind turn wasn’t to be taken lightly.

(Continued on page 78)

Other back-country hazard areas worth studying are the small lanes that lead into a depression in the topography; these are usual targets for deposits of sand and topsoil, and are very common in New England, the Southeast and hilly areas of the Midwest. Any downhill that passes through a gully or a heavily foliated cut in the land is suspect, too. Any canyon that acts as a natural water course will manage to junk up a road that winds along its bottom at one point or another.

In seasons of rainfall and landslide, chances are you cannot count on using the whole roadway for your essays in racing technique, due to the grit at the edges. Don’t feel badly, because even racers usually leave themselves a foot or two of leeway on controlled courses.

Roadways that pass by dams, lakes, quarries, rivers, large sanded parking lots and roadside rest areas are likely to be littered with grit, stones, sand or mud caused by erosion or even heavy traffic digging on and off the side of the road. The edges of the road are especially suspect in these places.

Obviously, you can’t really predict the future, and if we were to avoid all of these hazards perfectly, we’d probably kill ourselves from under-exertion and boredom. Nonetheless, if fast riding is your game, develop the mental discipline necessary to feel the countryside and what it has to offer. Reference the new conditions of the gray ribbon unfolding beneath you against what has come before. Sense the humidity and sense the countryside. After a while it becomes an exciting guessing game, a sensual way of adding accomplishment to your motorcycling.

It may not be nice, but it’s really fun to fool Mother Nature.

BAD WEATHER

Riding when the weather is bad requires a paradoxical combination of talents. You need the reaction time of a cat and the aggressiveness of a tree sloth. The catlike quality keeps you aware of each weather and road factor as it affects you. You are up-to-the-second on the possible effect of a patch of glaring ice, or the puddle stretching across your banking point in a turn just ahead. The slothlike quality prevents you from overcontrolling, and thereby imposing violent motions on your machine. The catlike quality interacts with the sloth in you, and tempers all calculations of stopping distance, turning ability and time to avoid hazards with the realization that only the gentle inputs of a sloth will keep you on your wheels.

(Continued on page 82)

Smoothness is the most important requirement for weather riding. But there are other requirements that must be met for each kind of weather and surface.

RAIN RIDING

As we mentioned before, rain is most treacherous just after is has started, lifting oil film to the road surface. But after it has rained heavily for 15 minutes or so, the slippery mix of oil and water tends to run off, leaving only a clean, wet surface that offers remarkably good traction (considering that it is wet!).

However, traction is not the only problem. If it continues to rain, certain spots in the road may accumulate thick puddles or pools of water. At moderate speeds, these may be relatively harmless. But if you happen to be traveling at 65 mph or more, the tires may begin to aqua-plane. The high speed of the tire surpasses its ability to move the water aside and contact the road; instead the tire rides up on a microscopic film of water that greatly diminishes traction. Your clue that this is happening is an odd lightness in the front wheel. If you have even a suspicion that the steering feels light, back off the throttle until you’ve lost about 10 mph. If you were to test the feeling of lightness, perhaps by wiggling the handlebars, your experiment could result in the front end washing out completely. Not all bike tires exhibit the same planing speed, so I can’t give you a hard and fast figure. Beware of aqua-planing particularly when the rear tire shows a flattening of profile from wear, or when both tires are brand new and have not yet been scrubbed in with a few hundred miles of riding.

Next time, more on riding in foul weather and poor light.

Current subscribers can access the complete Cycle World magazine archive Register Now

Dan Hunt

-

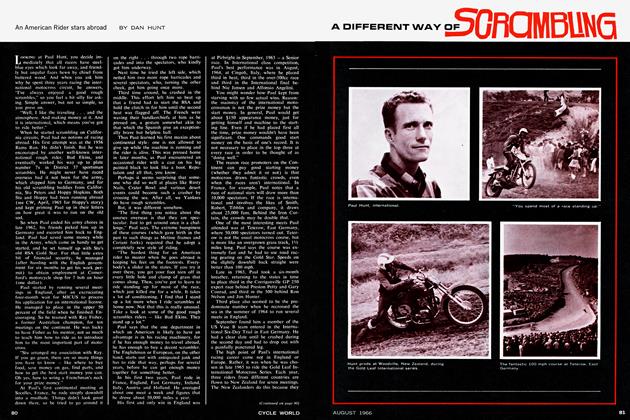

A Different Way of Scrambling

AUGUST 1966 By Dan Hunt -

Interview

Interview"Flat Track Racing Is Like Manure. You'd Like To Have Somebody Else Put It 'round Your Flower Bed, Because You Know It'd Do Some Good. But You Really Wouldn't Want To Put Your Hands In It...”

OCTOBER 1969 By Dan Hunt -

Features

FeaturesIf You Get Busted

APRIL 1970 By Dan Hunt