YAMAHA YZC125 MX

Cycle World Road Test

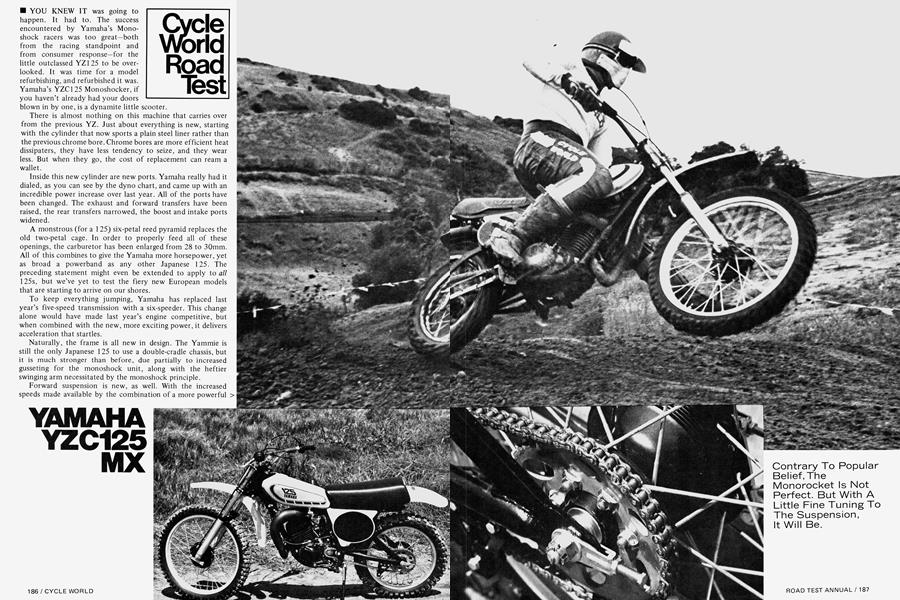

■ YOU KNEW IT was going to happen. It had to. The success encountered by Yamaha’s Mono-shock racers was too great—both from the racing standpoint and from consumer response—for the little outclassed YZ125 to be over-looked. It was time for a model refurbishing, and refurbished it was. Yamaha’s YZC125 Monoshocker, if you haven’t already had your doors blown in by one, is a dynamite little scooter.

There is almost nothing on this machine that carries over from the previous YZ. Just about everything is new, starting with the cylinder that now sports a plain steel liner rather than the previous chrome bore. Chrome bores are more efficient heat dissipaters, they have less tendency to seize, and they wear less. But when they go, the cost of replacement can ream a wallet.

Inside this new cylinder are new ports. Yamaha really had it dialed, as you can see by the dyno chart, and came up with an incredible power increase over last year. All of the ports have been changed. The exhaust and forward transfers have been raised, the rear transfers narrowed, the boost and intake ports widened.

A monstrous (for a 125) six-petal reed pyramid replaces the old two-petal cage. In order to properly feed all of these openings, the carburetor has been enlarged from 28 to 30mm. All of this combines to give the Yamaha more horsepower, yet as broad a powerband as any other Japanese 125. The preceding statement might even be extended to apply to all 125s, but we’ve yet to test the fiery new European models that are starting to arrive on our shores.

To keep everything jumping, Yamaha has replaced last year’s five-speed transmission with a six-speeder. This change alone would have made last year’s engine competitive, but when combined with the new, more exciting power, it delivers acceleration that startles.

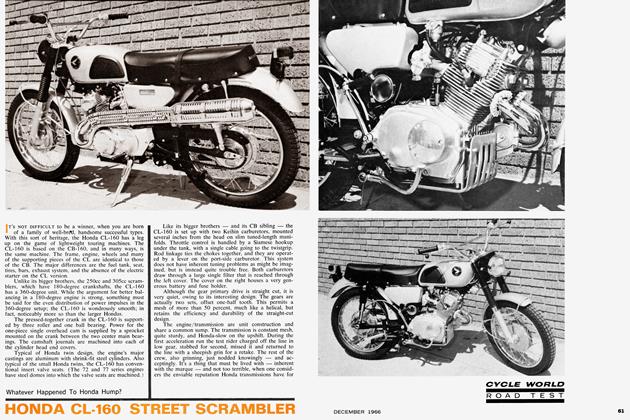

Naturally, the frame is all new in design. The Yammie is still the only Japanese 125 to use a double-cradle chassis, but it is much stronger than before, due partially to increased gusseting for the monoshock unit, along with the heftier swinging arm necessitated by the monoshock principle.

Forward suspension is new, as well. With the increased speeds made available by the combination of a more powerful engine, the six-speed gearbox and the long-travel monoshock rear end, the stock YZ125 front forks were heavily overtaxed. The YZC finds a pair of YZ250 forks supporting its front end. More about these in a minute. Along with the forks is a very light YZ250 front wheel.

Styling is exceptional. Not only do the engine’s new contoured side cases give the power plant a more rustic, businesslike appearance, but the traditional Yamaha black on yellow stripe scheme has never been more delightfully executed. It certainly stands out next to the somewhat drab gray appearance of Honda’s Elsinore.

The Yamaha is a screamer. It has a nice powerband considering its peak output, but rpm means horsepower and the Yamaha has more than its share of both. It starts to come on the ports at about 7500 turns and doesn’t start tailing off until nearly 11 grand. If you should ever have to lug the engine, it pulls willingly as long as the throttle is fed in slowly. Whipping the throttle open on such a situation will produce bogging that even the reed-valve won’t be able to prevent. Of course, for best performance, the engine should be buzzed, and buzzed hard. Here, the transmission ratios help. Being closely spaced, they do not let the rpm drop too much when upshifting.

The Yamaha got an exceptional amount of use during our test, simply because it was such a delight to finally have a bike that can not only blow off stock Elsinores and KX Kawasakis on the straights and off the starting line, but that can actually outhandle them, even though the YZC’s suspension is not set up right.

The forks are imprecise. There is none of the well-behaved damping that we found on last year’s YZ monoshocker, even though these forks are identical. The inconsistency of these units really isn’t par for the Japanese. Compression damping was good and the absorption of track irregularities was not harsh, but the rebound was really wacky. The front wheel would slam back into the ground rather than being more gently deposited as good forks will do. Even a change from the stock fish oil to Bel-Ray didn’t make the dampers behave at a level that we would label acceptable, considering engine performance.

At the other end is the monoshock. Again, the inconsistency surprises us. Our YZM250 Monoshock worked very well, Our MX400 Monoshock was even better. But the 1 25 is not as good. There is sufficient travel, and the spring rate is good for really hard bumps, but as the shock is delivered, there is just too much gas pressure. The monoshock is designed to be more sensitive to gas pressure than regular gas shocks because the pressure is variable. When the pressure is too high, the shock loses its sensitivity to smaller bumps. It takes large bumps to make it compress.

Such is the situation with the shock on our test bike. Larger potholes make it work, and when it works it does so very well. But it jumps and dances over smaller obstacles, and sometimes this can cause enough loss of traction to make a difference in a race. Also, when the rear end has to traverse braking bumps, the back end kicks and dances about. The solution is to alter the shock pressure. This takes a dealer with the proper tools and know-how. Next month we’ll tell you who does it and how they do it. We’ll also get the front end working right.

Racing in the 125 class is generally reserved for younger riders. The Yamaha is well tailored to their smaller physiques. For our six-foot staffers, the riding position was mildly cramped, although not uncomfortable. The Yamaha is very light up front. Wheelies can be performed in any of the lower four gears, simply by sitting back and dialing on the power.

Brakes were found to be excellent. The rear one was a tad oversensitive, but putting a slight crimp in the brake rod desensitized it a bit. Both wheels come with D.I.D. shoulderless alloy rims that are about the best thing money can buy. Traction is provided by a Dunlop Sports Senior 4.10-18 rear tire. The Dunlop delivers fantastic traction on tacky surfaces and traction as good as anything else when the track is dry. It also has knobs far up the sidewall for grip when the machine is heeled over. But the tire on our test bike, just like the Dunlop used during our Can-Am evaluation (CW, May ’75) started to chunk after a while. The rest of the tire was still in quite good shape and had many more races on it, but the chunking knobs made it useless.

Dunlop also provides the traction up front. But the 3.00-21 tire just isn’t the ticket for Southern California MX tracks. We replaced it with a 2.75-21 Bridgestone that came off a 125 Elsinore. This change helped the steering, but for greater improvement a 3.00 Bridgestone or Metzeler works wonders.

YAMAHA YZC125 MX

$990

Another alteration we found tremendously helpful was sliding the fork legs up through the triple clamps about an inch and a half. The rake reduction allows the front end to stick better, and stuffing the bike into a'tighter line is easier. For those who wish to use the YZC as a desert bike, extending the legs to their fullest provides better high-speed stability.

As long as we’re discussing faults, the handlebars are soft, the footpegs pack easily with mud, the shift lever comes with a little rubber pad that should be discarded, and the ignition has

DYNAMOMETER TEST HORSEPOWER AND TORQUE

zilch waterproofing. In fact, everytime we washed the little screamer, it would only run backwards until all of the external electricals dried off. Then everything was okay.

Cornering the bike was a unique experience. It doesn’t want to slide (no doubt the high center of gravity caused by the monoshock location was a contributing factor), yet it steered too well—even with the stock tire—to be much of a berm hunter. Then, after we changed the front tire, it became obvious. The YZC is an inside-line motorcycle. Much in the manner of a Maico, the bike has an innate ability to get into and hold a tight cornering line. Body positioning does help a little, but it doesn’t have as drastic an effect on steering as on some other bikes we’ve ridden. Also, the geometry allows quick square-offs, even in corners where traction is a problem.

As geared, the Yamaha is not only quicker, it is faster than any other Japanese 125. Overall gearing is very similar to Honda’s, but the Yamaha has about 2500 rpm that the standard Elsinore doesn’t. This is where the speed difference lies. Wide open in sixth, the YZC just pulls away from its competition. In acceleration, the Yamaha is quicker than a Honda, but not by a whole bunch. Also, it is not a particularly easy bike to get off a starting line because of the traction provided by the rear tire and the fact that the clutch is almost like a toggle switch. It’s either engaged or disengaged. Sit way forward, wing it and dump the clutch, and the front wheel still wants to kiss the sky.

The up-pipe and high top speed make this bike an ideal desert mount. Slap on an accessory tank (make sure you get one that will clear the monoshock unit), and you can ride for hours in the wide open spaces. For motocross, we didn’t like the particular bend in the handlebars. Sit-down-style desert riders will have little problem with the bars, but they caused premature arm cramping if we rode standing up for very long. The seat is on the narrow side, but well-padded and comfortable. Flexible plastic fenders are always a welcome asset.

Yamaha’s YZC125 Monocrosser is, without a doubt, the best Japanese 125 motocrosser currently available. It has the lead in both quickness and speed. It handles at least on a par with what is currently available (at least in stock form), although the new RM125 Suzuki that we just received is starting to show the Yamaha a thing or two in the handling department. The YZC’s six-speed transmission, the great power, the monoshock arrangement and the general appearance make it a desirable package.

We have spent part of this test detailing the things we didn’t like. If they appear excessive, it’s because our time on the Yamaha has been excessive. Deliberately so. We’ve had a chance to become more intimate with this machine than we normally do. We like it. It’s fun to ride and tremendously competitive. That’s why we’re going to keep it for a while and see what can be done with a little time, patience and a few bucks.

Until then, we’re going to continue to wring the living hell out of it. After all, if you had one, isn’t that what you’d be doing? ©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue