COMPETITION ETC

CAL RAYBORN MEMORIAL HALF-MILE RACE

DAN MAHONY

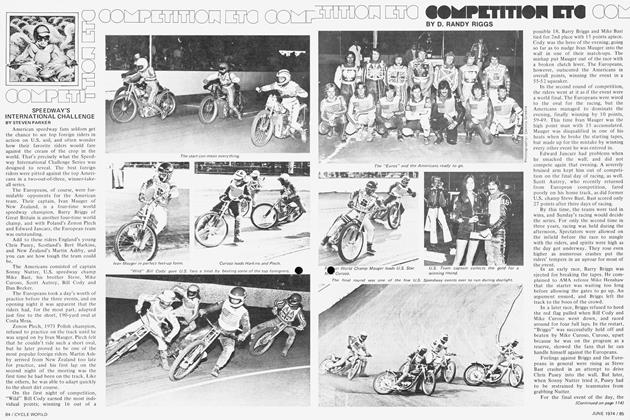

On December 29, 1973, one of the world’s best motorcycle racers was lost in a high-speed crash in New Zealand. Close to 6000 race fans from the San Diego area poured into South Bay Park Speedway on a Saturday night to show the family of Cal Rayborn that they remember.

Halfway through the evening, the racing was suspended for a few minutes to present to Jackie Rayborn nearly $15,000 in donations, including $6000 from Harley-Davidson, from the sale of Cal’s bikes, and $5000 from the promoter of the race, Don Basile.

When the checkered flag fell in the Expert final, 21-year-old Rick Hocking had won, and was presented with the first annual Cal Rayborn Memorial Award. It was Hocking’s first Expert half-mile start.

Hocking got off the line from the outside front row ahead of a Nationalclass field and never heard the sound of another motor for the whole race. In 2nd on the first lap was Gene Romero, followed by his teammate Kenny Roberts, then John Hateley and Tom White.

Hateley’s Yamaha began to sour almost immediately, and he dropped back to finish in the last running position. Trophy dash winner, Mert Lawwill, had been learning the track all night, and was now on the move from his so-so start. Mert moved up past White and Roberts and set out for Romero. Behind him, Roberts’ Yamaha flung a chain and put him out of the race.

A tight little group that incluJBH White, local rider Sal Paluso, Frank Gillespie and Ron Moore split into several directions when Kenny’s chain went. Paluso wound up 4th ahead of Gillespie and Moore, as Lawwill zapped Romero down the back straight. With nobody to race with, Hocking casually wheelied across the finish line to the delight of the fans.

Earlier in the evening, two local first-year Experts had set the two fastest qualifying times; Danny Hockie (Norton) and John Sperry (Triumph). Ron Moore and Don Castro were also to go to the three-lap trophy dash, but Castro got off hard in his heat trying to pass eventual winner John Hateley, and broke three ribs, his ankle and his knee cap.

Hateley just held off Roberts in that one by a wheel. Other heats were WQM by Romero and Hocking. To give y<§B an idea of how tough the competition was, the entire trophy dash lineup was in the semi, with Moore and Lawwill, along with Bob Sanders, transferring to the final.

Little Ron Toby of Bakersfield, despite getting his foot run over on the first lap, came from behind to pass early leader Scott Smith for the win in the 10-lap Junior final. Bud Smith finished 3rd over Art Fredenberg and Scott Marshall.

Bert Turner came from 8th place in the Novice eight-lapper to pass leader Pat Guthrie at the white flag only to lose the lead in the last corner, as Guthrie WFO’d back by to win it. Brent Knaver, Mitch Perri and Mark Smith rounded out the top five.

ON THE ICE

CHRIS CARTER

Ice racing, considered by many to be one of the most dangerous pastimes in the world, is one of the boom sports of the ’70s. In Europe, the crowds are flocking to watch this present-day equivalent of the Roman games by the thousands, and no wonder!

With 90 inch-long razor-sharp spikes ^flted into the front tire of each machine, and no less than 200 of these wicked-looking projectiles fastened to the rear tire, it is not just the 80-mph speeds that make this branch of twowheeled sports such a dangerous occupation.

Since the 1930s, ice racing has been restricted basically to Sweden and the Communist bloc countries, but since the introduction of the World Championships in 1966, other European countries have produced riders who look capable of challenging the super stars, if not actually beating them.

The acknowledged King of the sport is 32-year-old Russian, Gabtracman Kadyrov, who has won the World Title six times in its eight-year history. Of the two men to have interrupted Kadyrov’s almost total stranglehold on the Championship, one is, not surprisingly, Smother Russian, Boris Sanoradov, who won the crown in 1967. The other, Anton Svab, a Czech, won in 1 970.

Why is it that the Russians are so good at this sport? Well, their winters are long and cold, and that means there are plenty of natural venues for the sport; frozen lakes, even rivers, can be appropriated for race meetings, while in other countries farther south, artificial ice skating rinks have to be taken over for occasional ice racing events.

In Russia, it is claimed that there are 5000 competitors participating in ice racing, not all of them on 500cc machines. The range of classes stretches from 125cc two-stroke CZs, to the full-blown 500 Jawa. With 5000 riders to choose from, it is not surprising that every year the Russians produce yet another fresh face to thrill and delight

te crowds who watch the qualifying iges of the World Championship. Yet none of these men can match the skill of Kadyrov.

In other phases of motorcycle sport there are, or have been, “Masters”— Agostini in road racing, Sammy Miller in trials, Joel Robert in motocross. Kadyrov is head and shoulders above his rivals in ice racing.

At Inzell in the World Final of ’73, I saw him ride slowly round the outside of the bend during the warm-up lap before his fourth of five rides in the Sunday afternoon’s program. His three earlier races he had won by hugging the tight inside bend of the ice, but in this race, he was drawn on the outside of the start, and while the others shut off at the first turn, Kadyrov, having seen for himself where the smooth ice lay, blasted 15 mph faster than them round the outside to snatch the lead and hold it.

Like speedway racing, there is more to ice racing than just turning left, and really, it is dangerous even to compare the two sports. As in speedway, the races take place over four laps of an oval track. Unlike speedway, though, the 500cc machines are predominantly Jawa-powered, have a two-speed gearbox, and are thrown over to skim the surface of the ice as the riders go round the bend (as opposed to the broad-siding technique of normal speedway.

Point scoring is the same as in speedway—3,2,1—but while league racing brings in the crowds in Sweden and Russia, it is the individual World Championship that packs them in in the thousands elsewhere.

At Inzell, West Germany, scene of two World Finals in recent years, 4000 fans were locked out on the second day each time, and spectators desiring a good view, arrived to stand in the below-zero temperatures for up to six hours. This has got to be king-size enthusiasm!

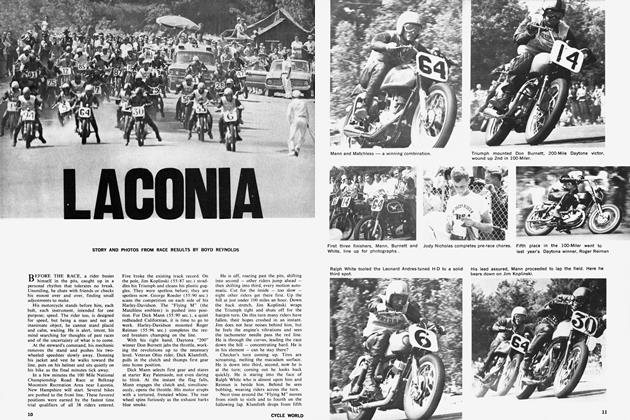

THE GREAT BEAR GRAND PRIX

STEVEN PARKER

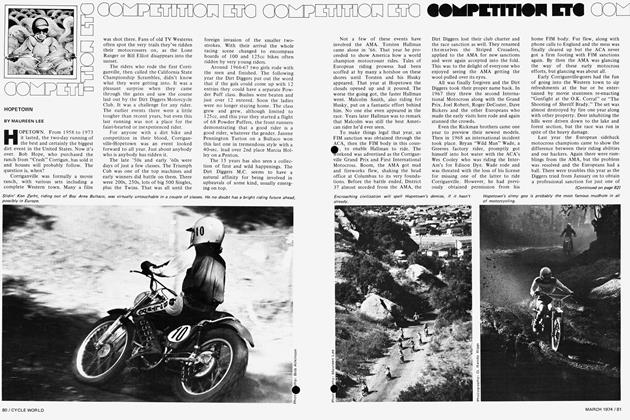

There is only one Grand Prix in the United States that forces racers to ride for almost 1 00 miles on a closed course incorporating both road racing and desert features. It is one of the most grueling races, both on men and equipment, in the world. The Orange County (California) Motorcycle Club has staged the Great Bear Grand Prix at Riverside International Raceway for the past two years, and the second running of the event provided some of the best and most exciting high-speed racing of the season.

The Great Bear draws the top names in off-road motorcycling, and the lineup this year was again star-studded. Some of the top desert racers in the country, and a goodly number of motocross big-names showed up to tackle the course, which was 8.9 miles in length and meandered off and on the asphalt track of Riverside.

Two events were run each day, each was 11 laps long and ran for approximately 97 miles (the promoters promised a longer course next year). The race is possibly the toughest closed course event run today, with a high number of machines and men dropping out from sheer exhaustion. The desert racers fared the best, probably because they are use to races running close to 200 miles, with specially-prepared machines to match.

Motorcycles were impounded at the track the day before the races for technical inspection, and when Saturday morning came, more than 640 riders stood on the line for the first race. The 100, 125, 175 and 250 Novices were ready to race, along with all Powder Puff classes. The riders left the lines in groups of 10-15, 10 seconds apart. It took a little over a minute to send all the machines on their way.

A 250 Novice, Robbie Brand of Barstow, claimed the lead in the first lap, fell down, and then recovered the first position, losing it only for a short time to Danny Waller, another 250 rider. Brand had the lead and rode an excellent race, leading the last five laps for the win. Waller had to settle for second position.

Powder Puffer Molinda Lea Nichols was injured and sent to the hospital with a fractured leg and internal injuries, the worst accident of the day. She was taken off the course by Rescue Three, a non-profit Barstow group that serves desert racers with recovery and first aid services. Rescue Three got one of their infrequent closed-course tryouts at Riverside, and they did a fantastic job helping both injured riders and spectators alike.

The now-famous Great Bear mudhole was opened for the first race and proved too much for most of the riders. A massive pile-up (more than 20 bikes at one time), forced officials to close the hole during the race. It remained closed for the rest of the weekend.

(Continued on page 100)

Continued from page 69

The second race of the day saw the Experts (100, 125, 175), Amateurs (250, 175, 125, 100) and some unclassified classes going at it. Jim Fishback, one of California’s premier desert racers, led the 175 Expert class for a time, until Tom Brooks, another big name desert ace, was able to replace him.

Brooks went on to victory, and Fishback dropped to finish 6th. Second place went to 250 Amateur Ron Haase on a Yamaha, and 3rd place honors were awarded to another 250 Amateur, Chris Henry on a Montessa. Fishback was to get his revenge during the final race of the weekend.

Sunday morning featured (besides a couple of bicycling streakers), old timers and sidehacks. The race was exciting, with the two-man hacks really attacking the desert and the asphalt with an all-out fervor. The old timers turned in some lap times comparable to those of the 175 Experts who had raced the day before, and the old timers’ win went to Dana Wilson, a 500 rider. Wilson rode a CZ to his win. The first hack team was that of J.T. and Pete Whitney. They piloted their Triumph to an impressive victory over a tough field.

The last race Sunday saw 500 (all classes) riders go against open Experts, 250 Experts and some 500 and 250 unclassified riders. The race featured the “names” in Southern California racing, and AMA star Dave Aldana (BSA) took the lead over the 750 bike field in the first lap.

Aldana led by more than a full minute, doing wheelies on the asphalt in front of the grandstands on full knobbies. The crowd was thrilled, but Jim Fishback had moved up 82 spots to the number-two position on his CZ during the first lap, and was destined to take the lead and the win from Aldana.

Aldana and Fishback traded the lead, and in the sixth lap, with Fishback in front, Aldana started to leak fuel and oil out of the four-stroke Single BSA. Fishback rode out the win, with Cordis Brooks, a 250 Expert, grabbing 2nd place. Mike Hannon, a 500 Expert on a Bultaco, took 3rd. Two-time world motocross champion, Rolff Tibblin, filling in at the last minute for Mitch Mayes, placed 6th in the event. Not bad for an old man.

(Continued on page 102)

Continued from page 100

Hurt in the event was 500 Expert Rod Sexton, riding a specially-prepared Puch. Sexton was run over by a Triumph after falling, and suffered a compound spine fracture and internal injuries, with cuts and bruises. The people from Rescue Three probably saved his life by rushing him from the track to the hospital.

The weekend was a great one. The organization of the OCMC was superb and announcer Larry Huffman added a lot to the show with his knowledge of the sport. Everybody looks forward to next year’s running of the Great Bear, on what officials promise to be a harder,

longer and completely new course.

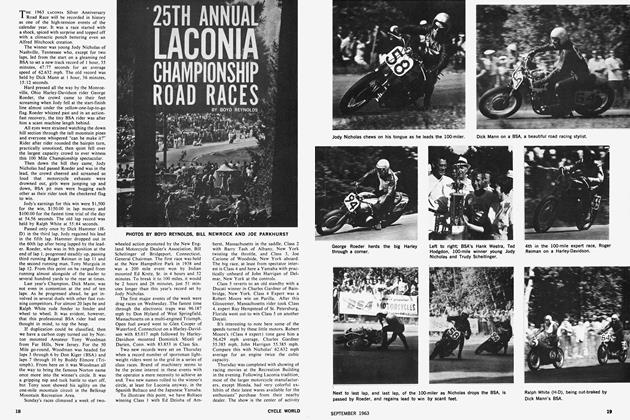

CURLEY FERN ENDURO

BOYD REYNOLDS

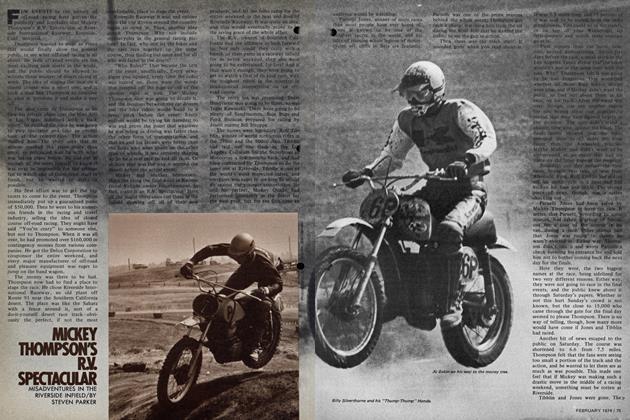

Switching from Husqvarna to Penton, Ron Bohn of Pittsburgh, Pa., lost only 32 points to win the first major national enduro in the Northwest. A consistent winner and ISDT Vase Team medal-holder, Bohn rode with precision around the tight 125-mile Curley Fern course near Whiting, N.J.

It was a cold, horrible, rainy day which, only a few miles north, deposited up to a foot of snow in a two-day storm. Alfie Hennrich was slated to repeat his win of last fall in the Sandy Lane National, which is held in the same area, but he lost one more point than Bohn .to take the Heavyweight Class on an XL350 Honda. Howard Tomlin followed in the same class with a 3rd overall score.

There were 650 entries; however, only 539 actually got underway, and of those, 30 percent finished the contest.

The South Jersey Enduro Riders did an excellent promotion job and even though the weather and the trail were wet, it was a superb contest. The trail was tight, the trees narrow and the water deep. There was little respite from riding that required every nerve and muscle in constant action. The usual Jersey sand was packed and the mud slick and gooey. A true test of an enduro rider’s skill, and Ron Bohn topped the best of them.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

August 1974 -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

August 1974 -

Departments

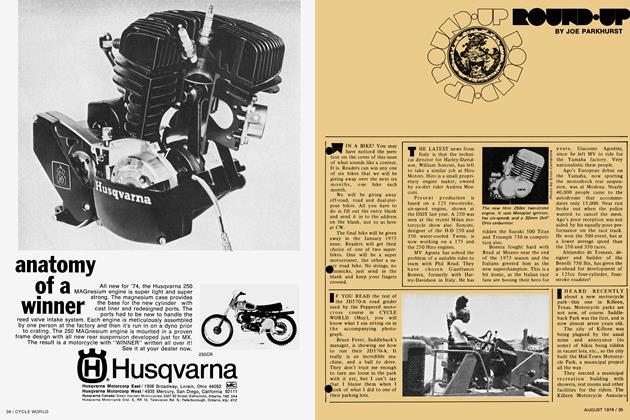

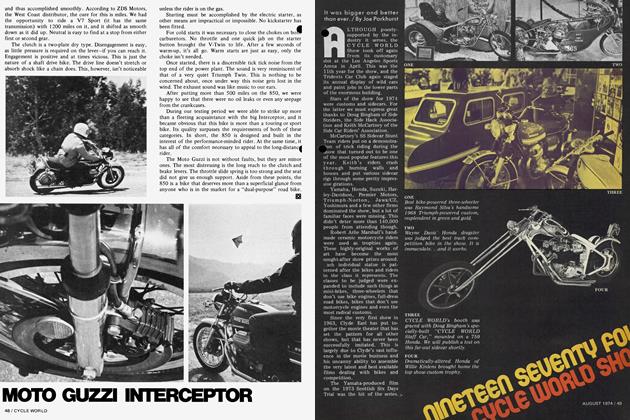

DepartmentsRound·up

August 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Features

FeaturesNineteen Seventy Four Cycle World Show

August 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Competition

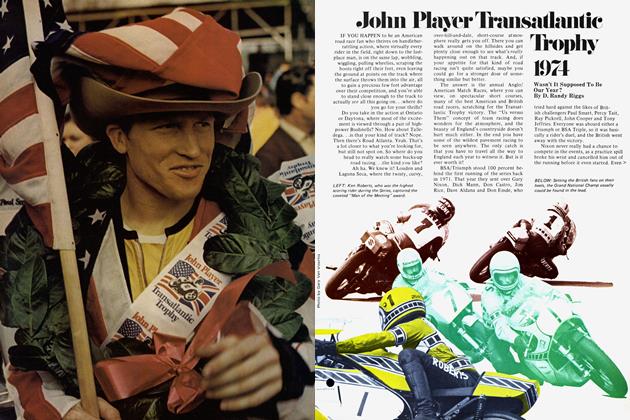

CompetitionJohn Player Transatlantic Trophy 1974

August 1974 By D. Randy Riggs