GARY SCOTT finished 2nd at San Jose, Denver and Louisville, then arrived at Columbus on Sunday afternoon, June 23rd, expecting to win his first dirt-track National of 1974. He finished 7th.

“It was the start, I made a bad start,” said Scott in that soft voice of his. “It’s the loose track surface here.”

“Maybe we should have gone up a little bit on the tire pressure, or changed the gearing,” suggested Bill Werner. Werner is Scott’s full-time mechanic on the Harley-Davidson team this year.

“No, the bike ran well and handled well,” insisted Scott. “It was me. It was just an off day for me.”

The sympathetic exchange was typical of the give-and-take helpfulness that exists between Scott, number-tworanked pro on the American Motorcycle Association’s Grand National tour during 1972-73, and the blond 30-year-old Werner, a former motorcycle racer turned mechanic. Since Gary Scott joined Harley-Davidson in January, he and Werner have been almost inseparable. Because Scott had never raced a Harley before, and Werner had never worked with Scott, they wanted to get to know one another. From the beginning, the partnership had jelled.

“I didn’t know much about Gary,” said Werner, “except that he was a quiet type of person. I knew he wasn’t the kind of rider pointing a finger at himself and saying, ‘I’m the greatest.’ I liked that. But I was surprised at how intelligent he was about motorcycle racing. Gary knows how he wants a motorcycle set up. And he works hard.”

In the five months between the opening Grand National race at the Astrodome in January, and the eighth one at Columbus, Scott and Werner had exhausted themselves making Scott’s XR750 dirt tracker just so. They tested in between races; they tried, discounted and incorporated things to aid the handling. And the hard work had paid off: By June Scott was up to second in GN points, beginning his now yearly chase of titlist and arch rival Kenny Roberts.

“They’re both fantastic riders, but their styles are different,” Werner said of Roberts and Scott. “Kenny rides the wheels off a dirt tracker; he reminds me of Bart Markel. But Gary is smoother, sort of a Gary Nixon style.”

Werner might have added that Gary Scott possesses a competitive streak, a will to win, that is apparently unmatched by anyone’s in motorcycle racing today, unless it is Roberts’. A racer since he was four (in micromidgets), Scott switched to motorcycles at 12. Throughout his early racing career he was pushed relentlessy by a zealous father who suffered three heart attacks in the process and who today rarely watches Gary race because he has a cardiac condition. “I was raised in a highly competitive atmosphere,” Scott

said. “I was brought up to be competitive. I like to win.”

Scott’s competitive streak is accompanied by a keen knowledge of motorcycle racing, odds, and what it takes to win. Though he is only 22, Gary Scott has been racing for 18 years. In other words, he has more miles under him than racers 10 years his senior. Gary’s overriding goal is to become Champion, Number One, and this is not because of the glory, or the money—although Scott is as avaricious as any motorcycle racer—but merely because Scott knows (though he won’t come out and say so), that he has the talent to be Number One. “I have a regular racing program for myself; I have my goals.” This year he switched from Triumph to HarleyDavidson because, after weighing everything, he decided that the Milwaukee team owned the fastest bikes.

Scott also turned down an attractive offer from Yamaha, Kenny Roberts’ team. The Yamaha racing team is so ritzy that it shows up in the pits at National races with special canvas chairs with the names of the team riders printed on the backs. Gary Scott did not care about having his name on the back of a canvas chair. “I just want to win motorcycle races.”

GN points are normally awarded at the rate of 150 for a 1st, 120 for 2nd, 100 for 3rd, and so on. For his 7th place at Columbus, Scott earned only 40 points. This was enough to preserve his 2nd place in the standings, but dropped him a full 363 points behind leader Roberts.

Now, to close the gap on Kenny Roberts, Scott would have to do something really spectacular, like win three Nationals in a row, which was impossible. Winning three straight Nationals is the equivalent of winning three straight Superbowls. Too much competition, too much pressure. Only legends like Joe Leonard, Carroll Resweber and Dick Mann had been able to win three or four in a row, and Mann’s accomplishment of this feat had taken place a full decade ago.

The three upcoming Nationals were the San Jose, Calif, mile-track race on July 7th, the Castle Rock, Wash. TT steeplechase July 13th, and the Ascot TT steeplechase July 20th.

“Nobody can win three,” Scott said. “But we can try.”

gARY SCOTT talked about the San Jose Mile: “I don’t care what you say. There is no way Roberts could have made that high line work that way again.” He was referring to an exciting race at San Jose in May at which Roberts, riding his Yamaha spectacularly, had passed Scott’s Harley high on the last corner and last lap.

“Kenny took a real gamble that he could get traction up there. It was a smart move, but it was risky for him. It might not have worked. He couldn’t do that every lap, and he couldn’t have even done it on the next lap.”

All of this said without a trace of sour grapes. Gary Scott’s mind isjjdy; he figures things out. He knev^»w Kenny Roberts had beaten him tn^ast time at San Jose and knew it wouldn’t happen again.

But Scott had been doing it long enough to know that motorcycle racing is not clear-cut. The element of surprise is always near, although Scott hates surprises. But during his 10-mile San Jose qualifying heat a screaming factory Triumph ridden by Mike Kidd surprised Gary, astonished him even.

Scott was leading and was sure he would win until Kidd, wearing red and white leathers, pushed his Triumph’s front wheel inside Scott’s Harley-Davidson during the 90-mph plunge into the corner after the back straight where the track narrowed. It was a tricky maneuver, and a dangerous one, and Scott was surprised that Kidd had such nerve. But Gary had still another surprise coimng to him. 19

Closing on Kidd, Scott finally pulled even. His speed was about 120 mph. By then both motorcycles were almost at the back straight corner again, Scott on the inside, Kidd on the outside. Scott was setting Kidd up. Because his Triumph was on the outside, Kidd would have to roll back the throttle earlier, or his speed would be too great for him to turn the bike for the corner at all.

But Kidd, fighting the handlebars, riding up on the rim, stayed level with Scott all the way around the corner. Scott won the heat, barely, but afterwards was mad at himself for underestimating Mike Kidd.

“Kidd took a hell of a chance riding like that,” Scott muttered. “And he surprised the hell out of me. I don’t know one other guy who would have left the gas on in a situation likeij^t, including Roberts.”

Kidd, a drawling, 20-year-old Texan and one-time child racer like Scott (Kidd started racing at age 12), had won the Columbus National and was coming on strong. Maybe too strong.

The field of 20 lined up for the 25-mile National. Because Scott’s had been the fastest heat, Gary had his choice of starting positions and picked the outside of the front row. The track surface looked solid there. Scott happens to be a master at getting a 75horsepower motorcycle away from a standing start in a hurry.

“A lot of people think you just rev up to 6000, drop the clutch and go. You don’t. There’s more to it than that.”

Kenny Roberts sat back on the second row, his black and yellow team Yamaha not as fast as it had been i^|e May event. It was not much of a^Re for 1st. Engine roaring, Scott pumped the twist-grip throttle, his back tire churned dirt, caught, and the number 64 Harley hurtled into the slippery first corner, leading.

A PAIR OF TRIPLES

Joe Scaizo

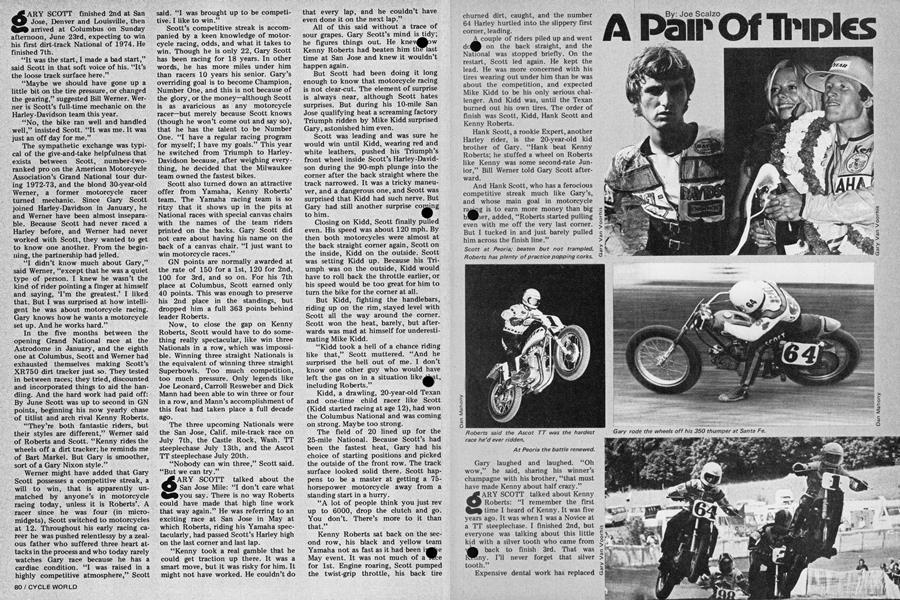

A couple of riders piled up and went dc^^ on the back straight, and the National was stopped briefly. On the restart, Scott led again. He kept the lead. He was more concerned with his tires wearing out under him than he was about the competition, and expected Mike Kidd to be his only serious challenger. And Kidd was, until the Texan burned out his own tires. The order of finish was Scott, Kidd, Hank Scott and Kenny Roberts.

Hank Scott, a rookie Expert, another Harley rider, is the 20-year-old kid brother of Gary. “Hank beat Kenny Roberts; he stuffed a wheel on Roberts like Kenny was some second-rate Junior,” Bill Werner told Gary Scott afterward.

And Hank Scott, who has a ferocious competitive streak much like Gary’s, and whose main goal in motorcycle ra^ng is to earn more money than big b®ier, added, “Roberts started pulling even with me off the very last corner. But I tucked in and just barely pulled him across the finish line.”

Gary laughed and laughed. “Oh wow,” he said, sharing his winner’s champagne with his brother, “that must have made Kenny about half crazy.” g ARY SCOTT talked about Kenny Roberts: “I remember the first time I heard of Kenny. It was five years ago. It was when I was a Novice at a TT steeplechase. I finished 2nd, but everyone was talking about this little kid with a silver tooth who came from back to finish 3rd. That was l^mny. I’ll never forget that silver tooth.”

Expensive dental work has replaced the silver tooth now (Roberts lost the original tooth in a dirt clod fight as a tot), and the “little kid” has become the country’s—perhaps the world’s—premier motorcycle racer. But after five years, Kenny Roberts still cannot shake Gary Scott.

Kenny Roberts is 20 days older than Gary Scott, an inch shorter, 10 pounds heavier, but, like Scott, is small, short and has a girl-sized 28-inch waist. Neither Roberts nor Scott is very outgoing, they don’t show emotion and you don’t know what they are thinking. They have a healthy respect for each other, although neither likes to say so.

“You know, like at Daytona this year,” Scott said. “I told Kenny I didn’t really want him to win the race, but I sure wanted to see him beat Agostini. And that’s how we feel about each other, I guess.”

At Castle Rock, on the edge of the Oregon and Washington borders, Scott would try to beat Kenny Roberts for the second week in a row. Castle Rock is a TT steeplechase track, meaning it has both right and left-hand turns. But because it has no straight and fast sections, speeds don’t exceed 65. Castle Rock is way out in the sticks, out in a wooded area next to a fast-moving river in which Gary Scott went for a swim on the afternoon of the National. Castle Rock is also famous for its very tough local riders who ride the place every week, know the track perfectly and take great pleasure in drubbing the visiting Grand National riders.

Bill Werner sent Scott out for practice. And Scott was not riding some lightweight motocross-type bike. His Harley was a 310-lb. brute, the same machine Gary had won on at San Jose, in fact, with its powerful dull black engine wedged so far forward in the frame that the cylinder heads almost touched the front tire. Front disc brakes had been added for Castle Rock’s sharp corners; they would be glowing dull red before the night was over.

Scott managed to hold off some of the locals and win his qualifying heat race. But Roberts, in his heat, had no such luck and lost to a local rider with the unlikely name of Charlie Brown.

As at San Jose, Scott boomed straight into the lead in the National. A bike length behind him, Kenny Roberts attempted a desperate but unsuccessful pass of the entire field on the opening lap and dropped to last place.

Riding recklessly, Roberts passed rider after rider, reached 6th place by the halfway mark, then dropped it in the sweeper corner, disabling his Yamaha. Roberts was down and out. This caused Hank Scott, who was flashing signals to his brother, to throw both hands into the air in glee.

But Gary Scott was too busy racing, and keeping his oversized Harley on the ragged edge, to take notice. A few laps

from the end, a local rider named Chuck Joyner (Yam), who had won the National the year before, caught up and bullied his way past Scott into the lead. Once in the lead, Joyner lost his rhythm. Twice he got into bad skids and the second time almost took down Scott, who was in the process of repassing him. Scott continued on to win his second National in six days. Suddenly Kenny Roberts’ GN points lead was cut to only 103.

Lying in the back of his transport van during the full-tilt run down the Pacific Coast to Los Angeles for the next National at Ascot, Gary Scott was so excited he could hardly talk.

gARY SCOTT talked about Gary Scott: “Yamaha wanted me to sign with them this year. We almost got together. But, uh, what they had in mind for me, I didn’t like. I mean, I have my own racing program. I didn’t want to be number two on their team behind Kenny Roberts.” And by now, mid-1974, Gary Scott had become first in the hearts of team HarleyDavidson.

“I don’t know what we’ll do if Gary wins this next one at Ascot, wins three Nationals in a row,” said grayhaired Dick O’Brien, boss of Harley’s racing division. “Might even all go out and get drunk or something.”

O’Brien had troubles; Harley-Davidson had troubles. The plant in Milwaukee had been closed for several weeks by a labor strike, which was putting a severe crimp in the racing program. Worse still, the racing team had been struck with a devastating string of injuries: Mert Law will and Mark and Scott Brelsford were all abed following crashes.

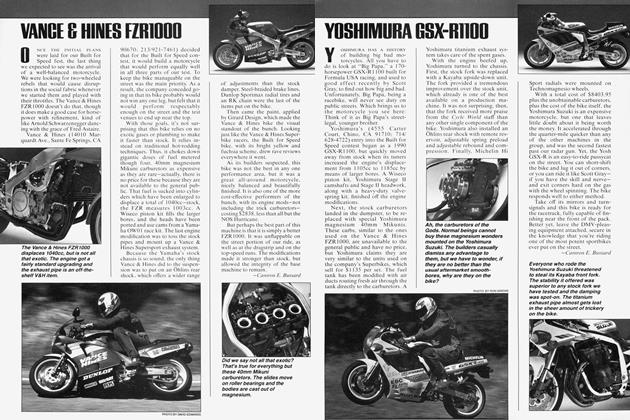

But Gary Scott was looking forward to Ascot. Ascot is the track on which Gary’s racing was practically formed. Ascot is also the track on which he saw Kenny Roberts’ silver tooth for the first time. And even though he and Bill Werner were badly outnumbered, and had virtually no teammates to assist them, Scott decided to gamble at Ascot, to go all out for the rarified third National win. Scott is not normally a gambler, not unless he can stack the odds in his favor, but at Ascot he figured, “What the hell?”

Daringly, he decided to gear his Harley, not for acceleration, but for top speed. Ascot’s TT steeplechase course is part half-mile flat track, part infield hairpins. The hairpin corners are tight and slow. They cut average speeds down to only 35 mph; the only real speed comes in the long flat-track corner before the finish line. Scott and Werner dipped deep into the tool box, fretting about gearing. They had no less than 30 different gear ratios from which to choose. They wanted the one that would allow Scott to really fire out of the half-mile corner.

This meant that Gary would have to ride through the infield in second gear, and could not afford to let himself get boxed in behind traffic. He would have to select his corner lines with cari^id would have to lead the National alTOie way. Scott took that lead right at the beginning; it was his third perfect start in three Nationals.

And he would win this National, too, even easier than he had won the others. Kenny Roberts placed a distant and desperate 2nd. Roberts had worked hard to get it; worked hard to even hold Scott in his sight. In the winner’s circle you could see that Scott looked relaxed, while points leader Roberts was harried. They shook hands.

It was the normally unflappable Roberts who showed the strain, too. “Sandbag?” he had snapped earlier when a reporter asked him if he would take it easy for the rest of the season and ride merely to finish Nationals rather than win them, take no chances and thereby preserve his point lead.

“How can you sandbag when yo(P>t Gary Scott after you?”

What had been a 363-point bulge three weeks earlier had shrunk to a mere 99. And what had seemed impossible before was glorious reality now. Gary Scott had somehow won three straight Nationals. Scott and Bill Werner had done it all by themselves, using the same motorcycle in all three races, with no assistance from teammates, and with the factory that sponsors them out on strike.

Scott even had Kenny Roberts a little bugged. “I would not change places with Roberts now,” Scott smiled. “The pressure to get Number One is on him more than me right now.”

gARY SCOTT perhaps made a mistake getting Kenny Roberts bugged. The following Sunday afternoon at the Laguna Seca road^^e National, Roberts won his first National in two months. He won it on a chainsnapped Yamaha TZ700 four-banger. He won it easily. Scott, trampled, placed 7th—a distant 7th. Now it was Kenny Roberts who had Gary Scott sounding bugged.

“Well, like the way Kenny won at Laguna Seca, it was so easy. And no one is supposed to win motorcycle races that easy. I mean, even when you have the fastest motorcycle and know you should win, racing, well, it shouldn’t be that easy. Nobody should just automatically win.”

The next National was at Willow Springs, a Chicago suburb. The track was a diminutive and crowded dirt oval, only a quarter of a mile long. Roberts, on a 360cc single-cylinder Yamaha, won again. Easily. Scott was 4th. Trarruifcd again.

Two days later, the Terre Haute, Indiana half-mile dirt-track National was postponed on account of rain. A week later, at Peoria, in the humidity of central Illinois, Roberts polished off another National. Just like that.

libras Roberts’ third straight win. >t^inl üy had he duplicated Scott’s earlier phenomenal feat, but had suddenly made it seem less than phenomenal. More importantly, Roberts had piled up so many points that his lead over Scott had exploded to better than 300.

“That Kenny, he can walk on water,” raved Roberts’ Yamaha teammate, Gene Romero. Reluctantly, Gary Scott seemed to agree.

“I thought I was an iron man, like Kenny Roberts,” breathed Scott. “But after today, maybe I’m not.”

Actually, Scott had done well to finish a reasonably close 2nd to Roberts at Peoria, which is a mean, dirty and very, very dangerous TT track at the bottom of a valley. But there was no way that Scott’s Harley-Davidson could have beaten Roberts’ Yamaha this day. Rogfcrts’ riding was too controlled, too perKt. By the finish of the 25 savage laps, most riders had demolished and blistered hands just from holding on. Only Roberts looked refreshed, relaxed. And only the way the veins were protruding from his pipe-stemmed arms gave any indication of how really hard Kenny had been grappling with his handlebars.

Six National races, two winners. The last time two riders were so evenly matched that between them they ripped up the AMA tour, was a dozen years ago, when Carroll Resweber and Bart Markel did so. But in 1974, in case you haven’t already guessed, nobody in racing can pump a motorcycle throttle quite like these two precocious 22-year-olds, Scott and Roberts, both of whom enjoy pretending that the other doesn’t exist.

“What’s the matter?” someone asked Rc^pts after Peoria. “Did Scott tick you off, winning three? Did you feel like you had to go out and do the same thing?”

Roberts shrugged. “Scott? Mad? Nah.” And he returned to signing autographs.

And Scott, his composure having returned, mumbled, “No, I don’t really care about beating Kenny Roberts. I just want to win motorcycle races.” But Gary knows that he can’t accomplish one without the other. Not in 1974.

A week after Peoria, at the Indianapolis Mile, Roberts blew his chance of winning four straight when his Yamaha broke down under him. He finished 19th. And Gary Scott, though he led briefly, managed only 4th.

The National was won, stirringly, by Romero. For the first time in nearly tvi^^nonths, Kenny Roberts and Gary St^P had been squeezed out of the headlines. But everyone knew they’d be back, fighting as usual. g]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

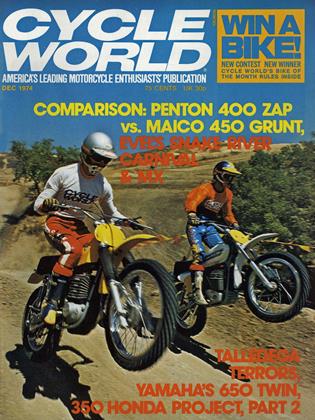

December 1974 -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

December 1974 -

Departments

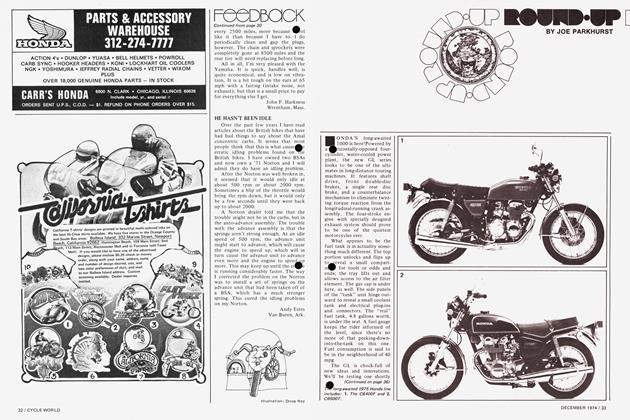

DepartmentsRound·up

December 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Features

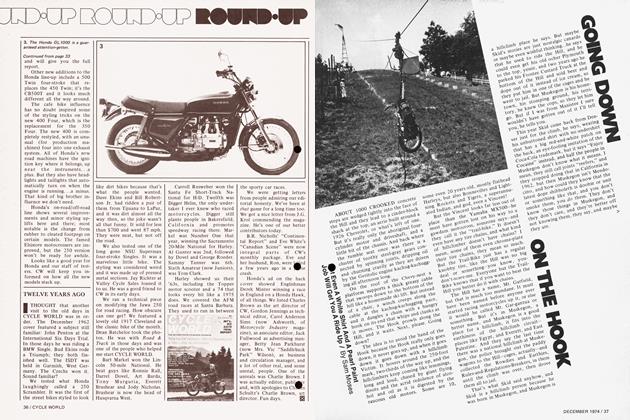

FeaturesGoing Down On the Hook

December 1974 By Sam Moses -

Features

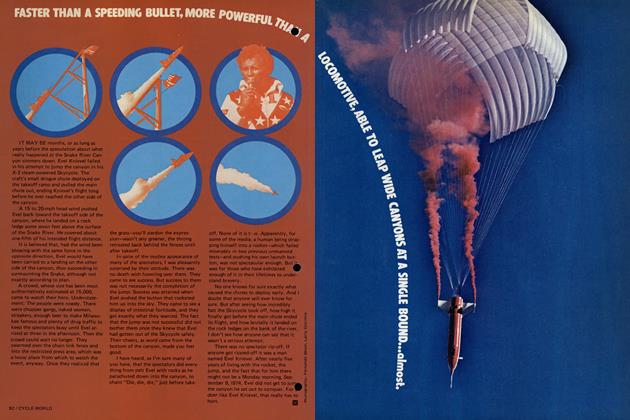

FeaturesFaster Than A Speeding Bullet, More Powerful Than A Locomotive, Able To Leap Wide Canyons At A Single Bound...Almost.

December 1974