ROAD RIDING

DAN HUNT

THE RIGHT MOTORCYCLE FOR YOU

Before you can ever know what kind of motorcycle you want, you really have to know yourself. What are your tastes, what are your needs, and how much can you spend to satisfy them?

Will you be riding alone? If so, you have more leeway than the person who contemplates going everywhere with his wife or girlfriend behind him. Riding alone, you can get by with a lighter machine and get just about all the performance you need. As a bonus, you’ll usually get a better-handling machine if it is light rather than heavy. That performance and handling will cost less in a lighter machine.

This same consideration may be used in reference to the lone rider’s size and weight. If you weigh more than 180 pounds, you may have to go for a slightly larger machine in order to get the kind of performance you want. If you weigh 155 pounds or less, the lighter machine may prove the equal of the bigger machine that is ridden by the 180-pounder.

In an automobile, 30-or 40 pounds is nothing because most cars already weigh at least a ton. On a motorcycle that 30 or 40 pounds may be close to eight or nine percent of the total weight package. Now add a reasonably-built, healthy American woman (is 120 pounds fair, girls?) to the passenger seat and you’ve added 25 percent to the overall weight of the bike. Somehow your bike doesn’t accelerate, climb hills or cruise like it used to and you’re wondering why.

Straight-line performance is not the only consideration in buying a motorcycle; you should take into consideration the following points, too.

1. Is handling a prime consideration in your mind? It may be if you ride primarily as a test of your own skill most of the time. Or if you ft&y yourself a bit of a road racer. In geiSRl, it may be said that if you trade off weight and brute performance from large displacement machines, you will get a better handling package in a lighter, smaller displacement machine.

2. How about fuel economy? It used to be that fuel economy was no consideration at all when buying a motorcycle. Quite simply, all motorcycles were economical when you stacked them up against cars. But modern technology— not to mention inflationary prices and fuel shortages—has managed to eliminate even that.

While 20 or 25 mpg sounds reasonable to most people, it isn’t reasonable during inflationary gas price periods. Take one of these gas-guzzling multicylinder ring-dings from Los Angeles to San Francisco at 20 mpg and it will consume 21.6 gal. over the 432 For some people that’s an expense trip...particularly when you start calculating oil costs to feed the automatic lubrication system.

If you ride 5000 miles a year at 20 mpg, your big-bore two-stroke will consume 250 gallons. Or if you drive the same mileage that the typical automobile owner drives each year, let’s say 12,000 miles, your bike will burn 600 gallons of gasoline and require 75 to 150 quarts of two-stroke oil.

(Continued on page 102)

Continued from page 100

Thus, the message is: Price it out before you buy. If your bag is shooting stoplights, maybe you don’t care. If you are, on the other hand, commuting 40 miles daily by motorcycle, or contemplating an extended trip across the U.S., with little extra money to spare, you want something more conservative.

One note. The high-miles touring rider who seeks fuel economy can go too far the other way. For example, one popular 350cc four-stroke Twin is quite economical in most situations, delivering as much as 40 to 48 mpg. But put it on a long-distance trip on which speeds may vary from 65 mph on up, and mileage may drop. We found that the CB350’s mileage, because you had to crank it in certain situations—such as desert headwinds or long climbs into the mountains—would drop to as low as 30 mpg. '

3. How about passenger comfort? Maybe you don’t care that your girl has sciatica of the nimbulus muscle. However, if she cares, pretty soon you’re going to care, or you ain’t gonna go ridin’ as often or as far as you thought you were.

Passenger comfort is pretty hard to eyeball without a test ride involving you and your passenger. But here are some things to look for: a) Adequate seat width) about 10-11 inches at the rear), b) Slightly beveled seat edges that don’t cut into the thighs, c) Padding that gives about an inch under heavy fist pressure. Any less and you’ve got yourself a potential torture rack. Any less and you also have a potential bottoming against the seat frame and lots of squirming as you both crowd and pinch together under distortion, d) Rear footpeg position that allows your partner comfortable extension of the legs; the angle of the thigh and foreleg should not be much less than 80 to 90 degrees, or blood circulation is reduced on long grinds. Further, the passenger should find it possible to use her legs and feet as leverage to brace against road shocks.

I will say here from personal experience that unless you have a real five-foottwo girlfriend, the abovementioned comfort requirements eliminate virtually every machine displacing less than 450cc. Tall, long-legged Sallys not only cost more to clothe, they cost more to carry around on a motorcycle.

(Continued on page 104)

Continued from page 102

One general tip: If you have a chance to try before you buy (surveys show that less than 40 percent of all new bike owners actually take a demo ride on the bike they buy), take your girl if she’s going to be a regular passenger. Ask her specific questions during your short ride. And remember that a demonstration ride will probably be shorter than any other ride you’ll ever take. If your loving partner complains even mildly about the hind seat, take note. It may be something that can be adjusted. If it isn’t Lord help you when you roll out of town for some real traveling.

4. Simplicity is yet another consideration that far too few riders perche. They buy for romance instead. The^rw superbike has four cylinders, four spark plugs that may or may not foul, four carburetors that may or may not stay in synch, and gobs of performance. A few thousand miles later, after they’ve learned what it costs to tune what is, in effect, the equivalent of a Ferrari Dino or Porsche 911S, they howl about tire and chain wear, plus the plugs and tune-ups they are buying. Then they run off to form consumer-complaint groups under the guise of “enthusiast” clubs.

I say, if you want your romance and all the far-out technical complexities, then you ought to take your knocks, too. If you want stolid reliability,

30.000 miles between tune-ups and

10.000 to 15,000 back tire wear, then you should be toning down your selfimage and looking at those less flashy, less mass-oriented bikes that ar^^esigned for the long-distance job.

If you can afford the luxury models, great. If not, the smaller-sized Twins, made by both the Japanese and the British, can offer the simplicity that you need. Simplicity is often considered synonymous with the two-stroke engine because it doesn’t have valve gear. When it comes to reliability, which is what we’d like to associate with simplicity, you’ll find that some two-strokes are simpler than others.

As a rough generality, piston-port two-strokes will be more reliable than rotary-valve two-strokes. And moderate-performance two-strokes will be more reliable than two-strokes that are tweaked to give startling performance. Four-strokes, too, show these same patterns and are equally inconsistent as a class; some leak and clatter, tions and burn valves, and other seem to go on forever.

(Continued on page 106)

Continued from page 104

Here are some of the characteristics that can be ascribed to categories of engines.

1. Four-stroke vertical Twins. The vertically-split crankcase types like the British vertical Twins tend to leak, because there are more seams that allow them to do so. The horizontally-split Twins, created by the Japanese, run cleaner. Both types tend to vibrate to an extreme at high engine speed and can be bothersome. Exceptions: The new counter-balanced Japanese Twins and the rubber-isolated British Twins.

2. Two-stroke vertical Twins. Generally smooth up to and including 500cc. Inch-for-inch, they consume more fuel than four-stroke Twins and generally require more spark-plug changes.

3. Two-stroke three-cylinders. In general, these are quite smooth, offer bristling performance. Many owners complain of spark-plug fouling and low mileage.

4. Four-stroke Threes. The original versions had their teething problems, but have settled in somewhat. They are smooth, offer extremely wide powerbands, and may or may not leak, depending on how conscientious British labor was feeling that day. Mileage is moderate, variable even within a given model; carburetion is inconsistent.

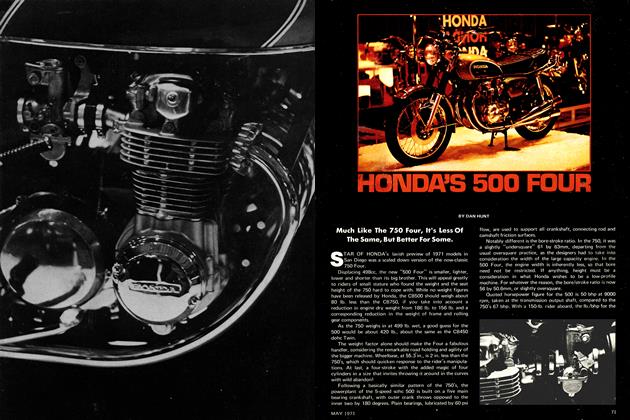

5. Four-stroke Fours. Generally reliable, generally smooth, generally leakfree. Plugs and carburetion can be bothersome. The smaller ones require rpm to obtain the desired action.

6. Opposed Twins. There’s only one current one—the BMW. It’s cleanÄinning, quiet, powerful, has that slWng but clunky transmission and, unlike the previous five categories, uses a shaft instead of a drive chain. Thus, no chain wear or adjustment problems.

7. V-Twins. Either shaft or chain driven. These engines are heavy but usually reliable, and their vibrations are sometimes more apparent than are those of other sorts of Twins. One exception: the sporting Ducati, which seems both lighter—for its 750cc size—and a trifle smoother.

8. Four-stroke Singles. The latest Japanese generation is quite tolerable, leak-free and easy to start. The big-bore oldies, when you can find them, are only for hard-core buffs and guys who know how to hustle for parts.

9. Two-stroke Singles. There are not

many that suit long-range road use. The majority are now manufactured^Üh broad powerbands and wide grear Mos for dirt riding. They double as commuting machines. |§1

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

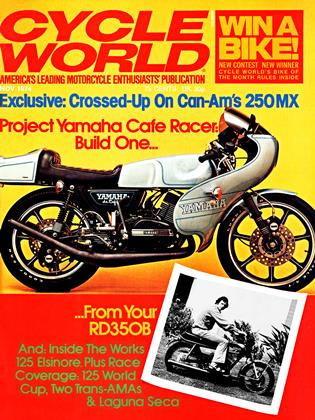

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMotorcycles, Rehabilitation And A Funky Jamboree

November 1974 -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

November 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

November 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Features

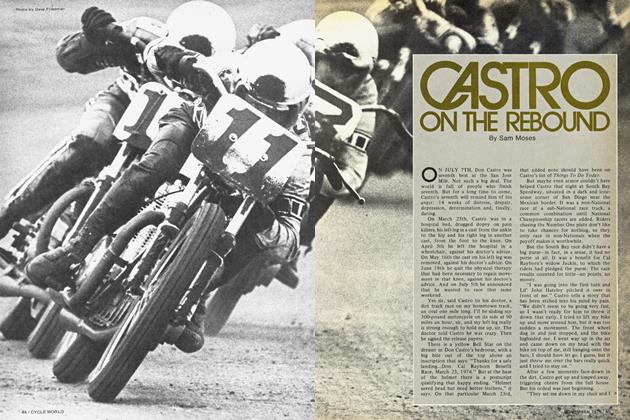

FeaturesCastro On the Rebound

November 1974 By Sam Moses -

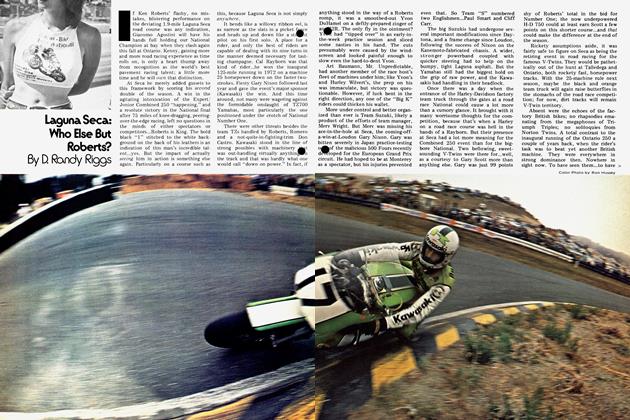

Competition

CompetitionLaguna Seca: Who Else But Roberts?

November 1974 By D. Randy Riggs