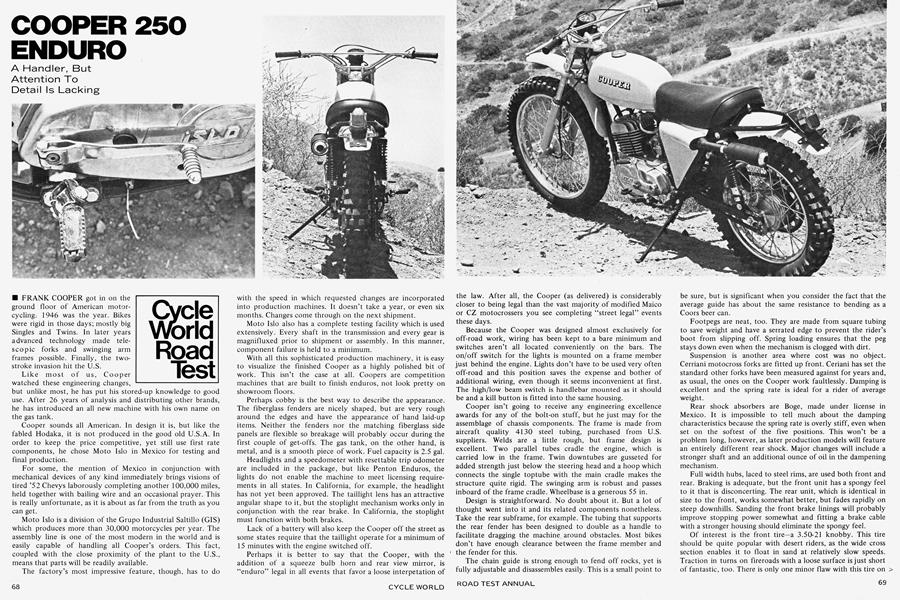

COOPER 250 ENDURO

Cycle World Road Test

A Handler, But Attention To Detail Is Lacking

FRANK COOPER got in on the ground floor of American motorcycling. 1946 was the year. Bikes were rigid in those days; mostly big Singles and Twins. In later years advanced technology made telescopic forks and swinging arm frames possible. Finally, the two-stroke invasion hit the U.S.

Like most of us, Cooper watched these engineering changes, but unlike most, he has put his stored-up knowledge to good use. After 26 years of analysis and distributing other brands, he has introduced an all new machine with his own name on the gas tank.

Cooper sounds all American. In design it is, but like the fabled Hodaka, it is not produced in the good old U.S.A. In order to keep the price competitive, yet still use first rate components, he chose Moto Islo in Mexico for testing and final production.

For some, the mention of Mexico in conjunction with mechanical devices of any kind immediately brings visions of tired ’52 Chevys laborously completing another 100,000 miles, held together with bailing wire and an occasional prayer. This is really unfortunate, as it is about as far from the truth as you can get.

Moto Islo is a division of the Grupo Industrial Saltillo (GIS) which produces more than 30,000 motorcycles per year. The assembly line is one of the most modern in the world and is easily capable of handling all Cooper’s orders. This fact, coupled with the close proximity of the plant to the U.S., means that parts will be readily available.

The factory’s most impressive feature, though, has to do with the speed in which requested changes are incorporated into production machines, it doesn’t take a year, or even six months. Changes come through on the next shipment.

Moto Islo also has a complete testing facility which is used extensively. Every shaft in the transmission and every gear is magnifluxed prior to shipment or assembly. In this manner, component failure is held to a minimum.

With all this sophisticated production machinery, it is easy to visualize the finished Cooper as a highly polished bit of work. This isn’t the case at all. Coopers are competition machines that are built to finish enduros, not look pretty on showroom floors.

Perhaps cobby is the best way to describe the appearance. The fiberglass fenders are nicely shaped, but are very rough around the edges and have the appearance of hand laid-up items. Neither the fenders nor the matching fiberglass side panels are flexible so breakage will probably occur during the first couple of get-offs. The gas tank, on the other hand, is metal, and is a smooth piece of work. Fuel capacity is 2.5 gal.

Headlights and a speedometer with resettable trip odometer are included in the package, but like Penton Enduros, the lights do not enable the machine to meet licensing requirements in all states. In California, for example, the headlight has not yet been approved. The taillight lens has an attractive angular shape to it, but the stoplight mechanism works only in conjunction with the rear brake. In California, the stoplight must function with both brakes.

Lack of a battery will also keep the Cooper off the street as some states require that the taillight operate for a minimum of 15 minutes with the engine switched off.

Perhaps it is better to say that the Cooper, with the addition of a squeeze bulb horn and rear view mirror, is “enduro” legal in all events that favor a loose interpetation of the law. After all, the Cooper (as delivered) is considerably closer to being legal than the vast majority of modified Maico or CZ motocrossers you see completing “street legal” events these days.

Because the Cooper was designed almost exclusively for off-road work, wiring has been kept to a bare minimum and switches aren’t all located conveniently on the bars. The on/off switch for the lights is mounted on a frame member just behind the engine. Lights don’t have to be used very often off-road and this position saves the expense and bother of additional wiring, even though it seems inconvenient at first. The high/low beam switch is handlebar mounted as it should be and a kill button is fitted into the same housing.

Cooper isn’t going to receive any engineering excellence awards for any of the bolt-on stuff, but he just may for the assemblage of chassis components. The frame is made from aircraft quality 4130 steel tubing, purchased from U.S. suppliers. Welds are a little rough, but frame design is excellent. Two parallel tubes cradle the engine, which is carried low in the frame. Twin downtubes are gusseted for added strength just below the steering head and a hoop which connects the single toptube with the main cradle makes the structure quite rigid. The swinging arm is robust and passes inboard of the frame cradle. Wheelbase is a generous 55 in.

Design is straightforward. No doubt about it. But a lot of thought went into it and its related components nonetheless. Take the rear subframe, for example. The tubing that supports the rear fender has been designed to double as a handle to facilitate dragging the machine: around obstacles. Most bikes don’t have enough clearance between the frame member and the fender for this.

The chain guide is strong enough to fend off rocks, yet is fully adjustable and disassembles easily. This is a small point to

be sure, but is significant when you consider the fact that the average guide has about the same resistance to bending as a Coors beer can.

Footpegs are neat, too. They are made from square tubing to save weight and have a serrated edge to prevent the rider’s boot from slipping off. Spring loading ensures that the peg stays down even when the mechanism is clogged with dirt.

Suspension is another area where cost was no object. Cerriani motocross forks are fitted up front. Ceriani has set the standard other forks have been measured against for years and, as usual, the ones on the Cooper work faultlessly. Damping is excellent and the spring rate is ideal for a rider of average weight.

Rear shock absorbers are Boge, made under license in Mexico. It is impossible to tell much about the damping characteristics because the spring rate is overly stiff, even when set on the softest of the five positions. This won’t be a problem long, however, as later production models will feature an entirely different rear shock. Major changes will include a stronger shaft and an additional ounce of oil in the dampening mechanism.

Full width hubs, laced to steel rims, are used both front and rear. Braking is adequate, but the front unit has a spongy feel to it that is disconcerting. The rear unit, which is identical in size to the front, works somewhat better, but fades rapidly on steep downhills. Sanding the front brake linings will probably improve stopping power somewhat and fitting a brake cable with a stronger housing should eliminate the spongy feel.

Of interest is the front tire—a 3.50-21 knobby. This tire should be quite popular with desert riders, as the wide cross section enables it to float in sand at relatively slow speeds. Traction in turns on fireroads with a loose surface is just short of fantastic, too. There is only one minor flaw with this tire on the Cooper. It scrapes on the fender when the forks come close to bottoming.

The rear tire is a conventional 4.00-18, which provides just the right amount of traction for the 28 bhp on tap. Even though the claimed power output is quite high for a 250cc enduro, the unit is surprisingly tractable.

A heavy flywheel is used which hampers throttle response a bit down low in the rpm scale, but it does make the Single a willing hillclimber when the chips are down. The rear tire can be kept spinning slowly without riding the clutch on any hill and this is often a great asset.

As the rpm builds past mid range, there is a noticeable increase in power, but the rush is not violent enough to cause concern—even when the machine is sliding on the ragged edge.

The power is there, but vibration is pretty heavy for a 250 and there is a lot of mechanical noise. Purchasers will have to live with the vibration, but the noise can be reduced by placing rubber blocks in between some of the fins on both the aluminum cylinder barrel and head. The head fitted to our test machine, incidentally, is also in the process of being redesigned. Compression ratio will probably remain at 10:1 but finning will be increased for greater cooling.

As on most competition oriented two-strokes, oil must be mixed in the gas at a ratio of 20:1. The mixture is delivered to the engine via a 32mm Mikuni carburetor. The Mikuni is a nice touch, as it offers easy starting, and parts are readily available.

A major problem in keeping any off-road motorcycle functioning properly is keeping the dirt out. As far as carburetor air filtration is concerned, Moto Islo has the situation well in hand with a properly shrouded polyurethane foam filter.

Keeping dirt and mud from packing around the clutch actuating mechanism, however, is going to be a problem. The actuating rod passes through a hole in the bottom of the right side engine case. A rubber plug which parts company with the machine in the first few miles of trailing is all that keeps mud and dirt from entering, which is added to a rather large volume of grit brought in by the rear chain. This means regular cleaning under the primary case, which is an annoying proposition to be faced with.

Primary drive is by chain to a hefty 15-plate clutch. Lever pressure is on the high side, but engagement is smooth and the unit will not slip, even after repeated abuse.

The transmission is a four-speed. Ratios are wide, yielding a good turn of speed, but the engine must be kept on the boil or it bogs after shifts. This is especially noticeable on hills or in deep sand. The reason for a four-speed is this: fewer gear changes mean less distance a rider looses to a rival every time he shifts. Since the engine in the Cooper isn’t powerful enough to pull the gap between gears without hesitation in all situations, though, a five-speed or lower overall gearing is in order.

The gear selector is located on the right and the shift pattern is conventional with low down and the rest up. Lever travel is stiff and decidedly long, making it difficult to engage gears quickly. Shifting action should improve with miles, although it still won’t be any too positive.

The gearbox does have one good attribute. It is strong. As mentioned earlier, all shafts are magnifluxed to detect any flaws. And, all gears have been widened at the base which makes it considerably more difficult to break off teeth when abusing the transmission. Aircraft quality 8620 gear steel is used as added insurance.

’Glasswork aside, the Cooper is capable of withstanding a lot of abuse—the kind every enduro rider expects in every event he enters. But more important, the pounding the bike takes isn’t transmitted directly to the rider. It’s an easy bike to ride because it doesn’t get thrown around much. Turn on the gas and the machine tracks straight. You don’t have to worry about being thrown over the bars. A close eye can be kept on the terrain and a lot of time can be speni in the seat resting, waiting for that impossible section you know is ahead.

COOPER

250 ENDURO

List price.............. ............$895

The bike is good in the rough, but is superb on fireroads. The front end never washes out in turns. Just dive in hot, get on the gas, and come out sliding.

With any competant rider on board, maintaining enduro schedules will be easy on any Cooper that is properly sorted out by its owner. The potential is there, but as delivered there is not enough attention to detail to make this latest Mexican/ American effort trouble-free.