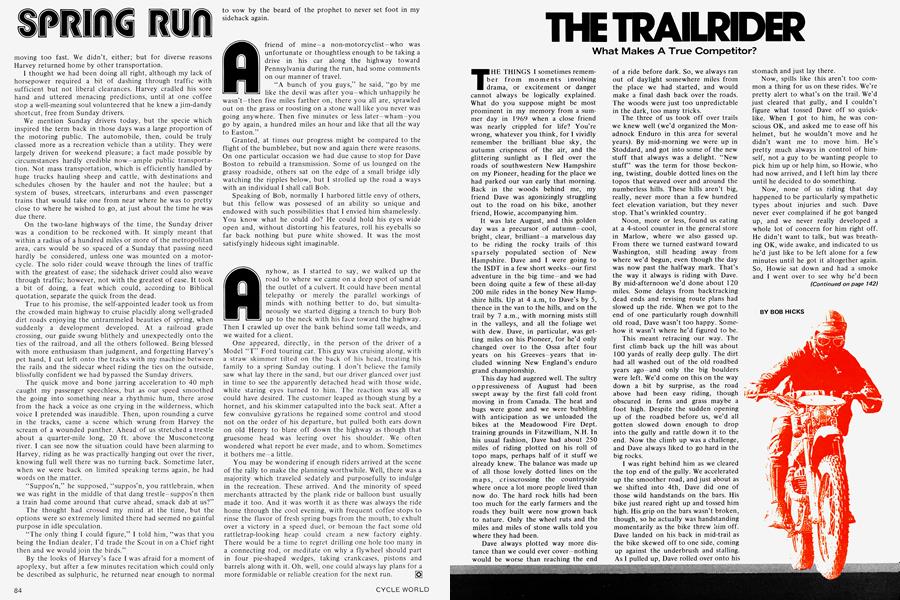

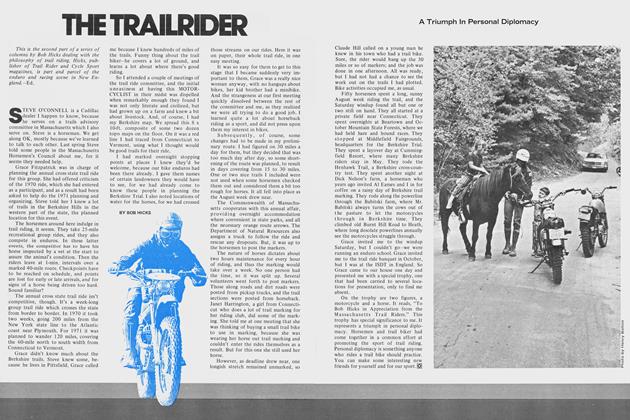

THE TRAILRIDER

What Makes A True Competitor?

THE THINGS I sometimes remember from moments involving drama, or excitement or danger cannot always be logically explained. What do you suppose might be most prominent in my memory from a summer day in 1969 when a close friend was nearly crippled for life? You’re wrong, whatever you think, for I vividly remember the brilliant blue sky, the autumn crispness of the air, and the glittering sunlight as I fled over the roads of southwestern New Hampshire on my Pioneer, heading for the place we had parked our van early that morning. Back in the woods behind me, my friend Dave was agonizingly struggling out to the road on his bike, another friend, Howie, accompanying him.

It was late August, and this golden day was a precursor of autumn-cool, bright, clear, brilliant—a marvelous day to be riding the rocky trails of this sparsely populated section of New Hampshire. Dave and I were going to the ISDT in a few short weeks—our first adventure in the big time—and we had been doing quite a few of these all-day 200 mile rides in the boney New Hampshire hills. Up at 4 a.m, to Dave’s by 5, thence in the van to the hills, and on the trail by 7 a.m., with morning mists still in the valleys, and all the foliage wet with dew. Dave, in particular, was getting miles on his Pioneer, for he’d only changed over to the Ossa after four years on his Greeves—years that included winning New England’s enduro grand championship.

This day had augered well. The sultry oppressiveness of August had been swept away by the first fall cold front moving in from Canada. The heat and bugs were gone and we were bubbling with anticipation as we unloaded the bikes at the Meadowood Fire Dept, training grounds in Fitzwilliam, N.H. In his usual fashion, Dave had about 250 miles of riding plotted on his roll of topo maps, perhaps half of it stuff we already knew. The balance was made up of all those lovely dotted lines on the maps, crisscrossing the countryside where once a lot more people lived than now do. The hard rock hills had been too much for the early farmers and the roads they built were now grown back to nature. Only the wheel ruts and the miles and miles of stone walls told you where they had been.

Dave always plotted way more distance than we could ever cover—nothing would be worse than reaching the end of a ride before dark. So, we always ran out of daylight somewhere miles from the place we had started, and would make a final dash back over the roads. The woods were just too unpredictable in the dark, too many tricks.

The three of us took off over trails we knew well (we’d organized the Monadnock Enduro in this area for several years). By mid-morning we were up in Stoddard, and got into some of the new stuff that always was a delight. “New stuff” was the term for those beckoning, twisting, double dotted lines on the topos that weaved over and around the numberless hills. These hills aren’t big, really, never more than a few hundred feet elevation variation, but they never stop. That’s wrinkled country.

Noon, more or less, found us eating at a 4-stool counter in the general store in Marlow, where we also gassed up. From there we turned eastward toward Washington, still heading away from where we’d begun, even though the day was now past the halfway mark. That’s the way it always is riding with Dave. By mid-afternoon we’d done about 120 miles. Some delays from backtracking dead ends and revising route plans had slowed up the ride. When we got to the end of one particularly rough downhill old road, Dave wasn’t too happy. Somehow it wasn’t where he’d figured to be.

This meant retracing our way. The first climb back up the hill was about 100 yards of really deep gully. The dirt had all washed out of the old roadbed years ago—and only the big boulders were left. We’d come on this on the way down a bit by surprise, as the road above had been easy riding, though obscured in ferns and grass maybe a foot high. Despite the sudden opening up of the roadbed before us, we’d all gotten slowed down enough to drop into the gully and rattle down it to the end. Now the climb up was a challenge, and Dave always liked to go hard in the big rocks.

I was right behind him as we cleared the top end of the gully. We accelerated up the smoother road, and just about as we shifted into 4th, Dave did one of those wild handstands on the bars. His bike just reared right up and tossed him high. His grip on the bars wasn’t broken, though, so he actually was handstanding momentarily as the bike threw him off. Dave landed on his back in mid-trail as the bike skewed off to one side, coming up against the underbrush and stalling. As I pulled up, Dave rolled over onto his stomach and just lay there.

Now, spills like this aren’t too common a thing for us on these rides. We’re pretty alert to what’s on the trail. We’d just cleared that gully, and I couldn’t figure what tossed Dave off so quicklike. When I got to him, he was conscious OK, and asked me to ease off his helmet, but he wouldn’t move and he didn’t want me to move him. He’s pretty much always in control of himself, not a guy to be wanting people to pick him up or help him, so Howie, who had now arrived, and I left him lay there until he decided to do something.

Now, none of us riding that day happened to be particularly sympathetic types about injuries and such. Dave never ever complained if he got banged up, and we never really developed a whole lot of concern for him right off. He didn’t want to talk, but was breathing OK, wide awake, and indicated to us he’d just like to be left alone for a few minutes until he got it altogether again. So, Howie sat down and had a smoke and I went over to see why he’d been tossed off so hard. What had done it was a pair of rocks hidden in the ferns. One had sort of a slant to it, and must have caught Dave’s front wheel just right so as to bounce it off sideways. Right where it went was another rock about like a curbstone segment, and between the two, at maybe 30 mph, they had trapped the front wheel just long enough to get the back end going up when it hit them, and the somersault was on. We ride over hundreds of these all the time, but the ferns never gave Dave a clue they were in there.

(Continued on page 142)

BOB HICKS

Dave finally rolled over, and back again, began to move his arms and head, testing himself for pains. Since he didn’t seem to be really hurting, we were getting just a mite impatient with him. As 1 said, none of us were much given to sympathy. If someone was really hurt, of course we helped him to get out of the woods, but an ordinary tumble never earned anyone riding with us much more than a “You OK?”—a question that didn’t imply expectation of a negative answer.

Finally Dave decided to talk about it. His back was hurting a good bit, it seemed, up between his shoulder blades. If he moved carefully, it was OK, and by degrees he stood up. We discussed going for an ambulance, most of these hill towns have a volunteer ambulance as part of the volunteer fire departments, and the local lads don’t mind a bit of excitement going out to rescue a hunter or even a trailbiker. Dave decided he didn’t care for that idea, they’d have to walk in a half mile up that gully to get to him.

We picked up his bike, got it straightened out, and started. He winced a bit getting a leg over the saddle, and tried riding it along the trail a bit, before stopping. His back was hurting from the bumps, even in low gear. This meant if he was going to ride it out, the gully was out. We’d have to go back the way we’d come, about two miles of woods road to dirt, thence to pavement.

So, we conferred, and decided that Fd go on back to get the van, Dave would ease along standing up to get out to the hard road, and Howie’d keep him company. I soon found myself racing along those winding blacktop country roads, heading for Fitzwilliam, 25 miles away by shortest route. The sun was now in my eyes, brilliant and glittering, the air was clear and it was a golden day, but my mind was on getting Dave home to whatever attention he might need. We’d all concluded he must have wrenched his back bad, because some probing hadn’t shown any of his ribs to be hurting him.

(Continued on page 143)

I flat flew to the van, loaded up my bike and headed back at 60 plus. With still 10 miles to go to get back to where they’d be waiting, I spotted two bikes coming along the other way, moving right along, too. Sure enough it was Dave and Howie. As Howie and I loaded the bikes, Dave explained how once he’d gotten on the smooth road he’d felt OK, aching but not really hurting. By now, we really figured he was just badly wrenched.

A couple of hours later we were back at Dave’s house. His wife was away for a few days, so we got together a spaghetti and meatball meal, and then Howie and I headed home. Dave said he was OK now, and would check into the infirmary in the morning when he went to work. He was mainly worried about shortening up his training for the Six Days, only three weeks away. He was, in fact, sort of angry with himself about it.

The phone rang about noon the next day. “Hello, Robert.” It was Dave, somewhat subdued sounding. “So, what’s the word?” I asked him. “Not good, I’m afraid,” was his dispirited answer. Bad news.

Dave had gone into the infirmary at Harvard when he arrived in Cambridge after a 20-mile drive, and asked to have his back X-rayed. He was told to go over and sit down until they could get to him. Finally they took the X-rays, and he put on his shirt and went back out to wait in the waiting room. When the door opened, the intern’s first words to him were, “Don’t move!” Dave didn’t, though he was surprised. Nobody’d seemed much concerned when he’d told them what was bothering him.

Well, they came out with one of those tables on wheels, and rigged this brace all around him before easing him aboard. He was whisked to a room, and before he hardly knew it, was strapped onto a sort of rig on a bed so he just couldn’t move his body at all.

“David, you are a very lucky guy,” the doctor told him then. “You have three crushed vertebrae in your upper spine. Nothing has moved so as to threaten the spinal cord, luckily.”

So Dave didn’t get to go to the Six Days in Germany that September. Instead, he spent six weeks in a traction rig, several months in a body cast, and much of the next year wearing a body brace. They let him play handball when he got into the body brace, though. It made him clumsy, he said. He didn’t get to trail ride for almost a year. It wasn’t until the fall of 1971 that Dave finally made it to the ISDT, on the Isle of Man. He got himself a Gold Medal in his first try. m

View Full Issue

View Full Issue