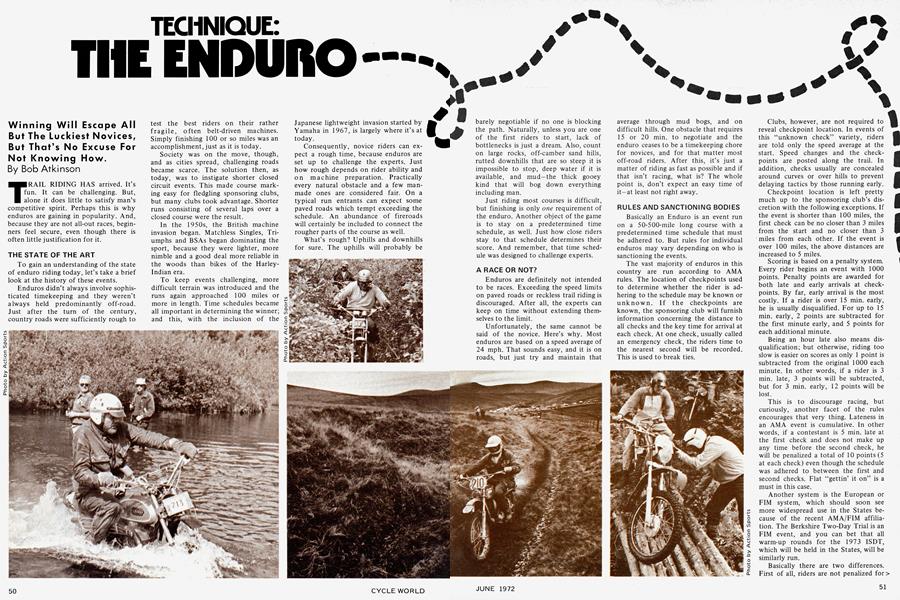

TECHNIQUE: THE ENDURO

Winning Will Escape All But The Luckiest Novices, But That's No Excuse For Not Knowing How.

Bob Atkinson

TRAIL RIDING HAS arrived. It's fun. It can be challenging. But, alone it does little to satisfy man's competitive spirit. Perhaps this is why enduros are gaining in popularity. And, because they are not all-out races, beginners feel secure, even though there is often little justification for it.

THE STATE OF THE ART

To gain an understanding of the state of enduro riding today, let’s take a brief look at the history of these events.

Enduros didn’t always involve sophisticated timekeeping and they weren’t always held predominantly off-road. Just after the turn of the century, country roads were sufficiently rough to test the best riders on their rather fragile, often belt-driven machines. Simply finishing 100 or so miles was an accomplishment, just as it is today.

Society was on the move, though, and as cities spread, challenging roads became scarce. The solution then, as today, was to instigate shorter closed circuit events. This made course marking easy for fledgling sponsoring clubs, but many clubs took advantage. Shorter runs consisting of several laps over a closed course were the result.

In the 1950s, the British machine invasion began. Matchless Singles, Triumphs and BSAs began dominating the sport, because they were lighter, more nimble and a good deal more reliable in the woods than bikes of the HarleyIndian era.

To keep events challenging, more difficult terrain was introduced and the runs again approached 100 miles or more in length. Time schedules became all important in determining the winner; and this, with the inclusion of the Japanese lightweight invasion started by Yamaha in 1967, is largely where it’s at today.

Consequently, novice riders can expect a rough time, because enduros are set up to challenge the experts. Just how rough depends on rider ability and on machine preparation. Practically every natural obstacle and a few manmade ones are considered fair. On a typical run entrants can expect some paved roads which tempt exceeding the schedule. An abundance of fireroads will certainly be included to connect the rougher parts of the course as well.

What’s rough? Uphills and downhills for sure. The uphills will probably be barely negotiable if no one is blocking the path. Naturally, unless you are one of the first riders to start, lack of bottlenecks is just a dream. Also, count on large rocks, off-camber sand hills, rutted downhills that are so steep it is impossible to stop, deep water if it is available, and mud-the thick gooey kind that will bog down everything including man.

Just riding most courses is difficult, but finishing is only one requirement of the enduro. Another object of the game is to stay on a predetermined time schedule, as well. Just how close riders stay to that schedule determines their score. And remember, that time sched ule was designed to challenge experts.

A RACE OR NOT?

Enduros are definitely not intended to be races. Exceeding the speed limits on paved roads or reckless trail riding is discouraged. After all, the experts can keep on time without extending them selves to the limit.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of the novice. Here's why. Most enduros are based on a speed average of 24 mph. That sounds easy, and it is on roads, but just try and maintain that average through mud bogs, and on difficult hills. One obstacle that requires 15 or 20 mm. to negotiate and the enduro ceases to be a timekeeping chore for novices, and for that matter most off-road riders. After this, it's just a matter of riding as fast as possible and if that isn't racing, what is? The whole point is, don't expect an easy time of it-at least not right away.

RULES AND SANCTIONING BODIES

Basically an Enduro is an event run on a 50-500-mile long course with a predetermined time schedule that must be adhered to. But rules for individual enduros may vary depending on who is sanctioning the events.

The vast majority of enduros in this country are run according to AMA rules. The location of checkpoints used to determine whether the rider is ad hering to the schedule may be known or unknown. If the checkpoints are known, the sponsoring club will furnish information concerning the distance to all checks and the key time for arrival at each check. At one check, usually called an emergency check, the riders time to the nearest second will be recorded. This is used to break ties.

Clubs, however, are not required to reveal checkpoint location. In events of this "unknown check" variety, riders are told only the speed average at the start. Speed changes and the check points are posted along the trail. In addition, checks usually are concealed around curves or over hills to prevent delaying tactics by those running early.

Checkpoint location is left pretty much up to the sponsoring club's dis cretion with the following exceptions. If the event is shorter than 100 miles, the first check can be no closer than 3 miles from the start and no closer than 3 miles from each other. If the event is over 100 miles, the above distances are increased to 5 miles. -

Scoring is based on a penalty system. Every rider begins an event with 1000 points. Penalty points are awarded for both late and early arrivals at check points. By far, early arrival is the most costly. If a rider is over 15 mm. early, he is usually disqualified. For up to 15 mm. early, 2 points are subtracted for the first minute early, and 5 points for each additional minute.

Being an hour late also means dis qualification; but otherwise, riding too slow is easier on scores as only 1 point is subtracted from the original 1000 each minute. In other words, if a rider is 3 mm. late, 3 points will be subtracted, but for 3 mm. early, 12 points will be lost.

This is to discourage racing, but curiously, another facet of the rules encourages that very thing. Lateness in an AMA event is cumulative. In other words, if a contestant is 5 mm. late at the first check and does not make up any time before the second check, he will be penalized a total of 10 points (5 at each check) even though the schedule was adhered to between the first and second checks. Flat "gettin' it on" is a must in this case.

Another system is the European or FIM system, which should soon see more widespread use in the States be cause of the recent AMA/FIM affilia tion. The Berkshire Two-Day Trial is an FIM event, and you can bet that all warm-up rounds for the 1973 ISDT, which will be held in the States, will be similarly run.

Basically there are two differences. First of all, riders are not penalized for early arrival at checkpoints, although they cannot proceed onward until their scheduled arrival time. One point is still subtracted for each minute late, but only from check to check. In other words, if a rider is 5 min. late to the first check, but rides from check one to check two at the prescribed rate, only 5 points are lost. Remember, in the AMA system the same set of circumstances would cost 10 points.

At first, FIM events appear easier—as long as riders are good enough to beat the schedule. Why? Because early arrival affords an opportunity to perform some maintenance, rest-up or what have you. And, if a novice is late in one section, he doesn’t have to make up that time.

But, FIM events usually contain one additional obstacle—the special test. Special tests can be anything from timed laps around a motocross course, to timed hillclimbs, to a comparison of acceleration taken at the beginning and end of an event. Special points gained in this manner usually determine the overall winner as several competitors are likely to have similar scores through the checks.

Unfortunately, racing isn’t really discouraged in this system, either, as there is no penalty for early arrival. The ideal system probably doesn’t exist, but Bob Hicks’ Trailrider article elsewhere in this issue explains a third system that he hopes will end this problem.

COURSE MARKING

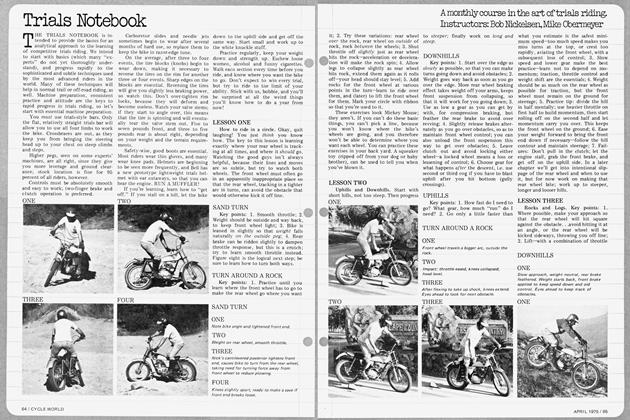

Now that the basic rules have been explained, let’s take a brief look at course marking. Usually arrows are used, but courses may be marked with lime and ribbon or a combination of arrows and lime.

Arrows will usually be a specific color to distinguish them from others that may be in the area from a previous event. Arrows pointing straight up mean just that—go straight. Arrows slanting downward at an angle mean that a turn in the direction of the arrow is ahead. The actual turn will be marked by a horizontal arrow pointing in the direction of the turn. About the only one that isn’t immediately obvious is arrows pointing straight down. These indicate danger and usually mean some superbad obstacle. Respect this one. To determine earliness or lateness, the rider must add his starting number to key time posted at each check. For example, if a rider draws the number 20B and key time at check 1 is 9 a.m., his prescribed arrival time is 9:20 a.m. If he arrives at 9:25, he is five minutes late, etc. Key times will be posted at all checkpoints.

A course marked with lime is somewhat vaguer. Lime looks a lot like chalk dust and is distributed by throwing a bag of the stuff on the ground. As long as riders pass some lime occasionally, or some colored ribbon tied to a branch, they know that they are still on the course.

Two or three splotches of lime in a row indicate a turn on the side of the trail that the lime is located. The actual corner should be very close to the last patch of lime and an additional lime marker will follow directly after the turn. If the trail branches out in several places at the point of the turn, a card with the letter “W” will usually be just past all the wrong intersections.

Danger is indicated by three lines of lime stretched across and to the side of the trail. Speed should be reduced promptly.

It sounds simple and it is—especially since there are usually several guys in view ahead on the trail. It isn’t required that everyone stay precisely on the trail, either, as long as corners aren’t cut. Often, however, natural terrain features prevent any deviation from the prescribed route. If a rider is off the trail and is passing through an old excavation site or mining area, he should take additional care to avoid open shafts. It sounds dumb, but occasionally you hear of some guy going down an unmarked mineshaft head first.

KEEPING TIME, STAGE I

As we indicated earlier, riding a well laid out enduro course is always difficult and is sometimes seemingly impossible for the novice. Therefore, stage one or novice timekeeping is a snap. A speedometer to stay close to the average speed on long pavement sections and a watch is all that are necessary. On the trail, novices should ride as fast as they can as they are late more often than not.

At each checkpoint, though, novices should see how far they are behind schedule. It’s good practice for quick calculations when novices get good enough to arrive early, too.

The concept of key time was developed because it isn’t practical to start every entrant at the same time. Consequently, the key time schedule is set up for a mythical rider who is allowed to depart at the official starting time. The first actual competitor departs 1 minute later and therefore must add his starting number (IA, IB, etc.) to key time to determine whether or not he is on schedule, just like all the rest.

Since all competitors must do some addition, the concept is an equalizer of sorts. For high numbers, though, the addition can become complex.

Still, for novices, stage 1 is purely for practice until enough proficiency is acquired to enable early arrival occasionally.

KEEPING TIME, STAGE II

For stage II timekeeping, that watch and speedometer become a necessity. A second watch and some time/distance charts should also be added to the equipment. The original watch, as in stage I, is used primarily to determine early or late arrival at checkpoints. But, instead of leaving the watch set to the actual time of day, it is reset to key time as the event is started. The watch will then correspond exactly to the key times posted along the course if the rider is on time. It’s worth it because it eliminates all addition. A glance is all anyone needs to tell if he is on schedule.

The second watch can either be a stopwatch that registers hours as well as minutes and seconds or just another wristwatch. The second watch is reset at (or clicked to if it is a stopwatch) 12:00 noon at every checkpoint or speed change along the course. It is used exclusively with the odometer and a time/distance chart to compute if the schedule is being maintained at any given point along the course. For example: Rider 1A is maintaining a posted 24 mph schedule and his 2nd watch registers 40 minutes, or 12:40 for wristwatches. A glance at the 24 mph time/ distance chart (see example) tells him that his odometer should read 16 miles. If it reads 14, rider 1A is 5 min. late, etc.

The best type of speedometer/ odometer that can be used with this system is a front wheel driven unit with the odometer resettable both forward and backward. The odometer should also register in tenths of a mile. It is preferable to have a front wheel driven unit, as those driven off the rear wheel register wheelspin and are therefore less accurate.

Time/distance charts (see examples) should contain all the popular speeds and can be figured for every minute, every two, five, or what-have-you. The examples furnished are figured for every minute and a wide variety of speeds. The chart each individual designs for his machine, however, should contain as few numerals as practical, as this makes the thing easier to read. Stopping on the trail to read a time/distance chart is defeating the intended purpose. >

KEEPING TIME, STAGE III

Perhaps the ultimate timekeeping method is a takeoff on the stage II system, but instead of using a separate watch and chart the two are combined. To accomplish this, a clock is used with all but the minute hand removed. A circular time/distance chart replaces the numerals on the face as well. Therefore, the minute hand actually reads miles and can be compared directly to the odometer.

This system is “trick,” but there are lots of others that work equally well. In the end, the best system is one designed by the individual rider to suit his own riding style and ability.

HOW TO ENTER

Entering is the easiest part of the game, but it can’t be done at the last minute, as there are a couple of associations that usually require joining.

Prior to entering any AMA-sanctioned event, membership is required. The cost is $7 for one year and application forms can be obtained at most bike shops. For any additional information, or if forms are not readily available, write to the American Motorcycle Association, P.O. Box 231, Worthington, OH 43085. In general, allow three weeks for this.

In most areas of the country, AMA membership is all that’s required before obtaining a sponsoring club’s entry blank and mailing it off before the cut-off date. There are exceptions, however, like New England. Clubs affiliated with the New England Trail Rider Association require that all entrants have a valid enduro license. These licenses are issued to novices after completing a short enduro school offered by the association. The reason for this additional requirement is two fatal accidents—both of which probably wouldn’t have occurred had the novices involved understood the rules and course marking!

Also, if one rides AMA events, and hopes to accumulate points toward becoming an expert or class champion, it is necessary that he also join the AMA District in his area. District application forms may be obtained from competition-oriented bike shops, or at district events. The cost is around $3 per year.

Districts also print schedules of events, and are a source of the names and addresses of all sponsoring clubs. Entry blanks can be acquired by writing the club direct and this is often a better method than chance acquisition at the local bike shop.

The easiest way to stay current on events and where to obtain entry

blanks, though, is to subscribe to a local weekly motorcycle newspaper. These usually print up-to-date lists of events and the current addresses of sponsoring clubs. Cut-off dates usually accompany the entry information, so don’t procrastinate if you want to ride.

MACHINE PREPARATION

All that remains is checking over the bike. A good place to begin is the frame. Check it for cracks around all the welds. If there are any breaks, have them rewelded. Don’t take chances. The same goes for the handlebars. Broken handlebars mean a crash every time.

Next check and lubricate all the control cables. If they are frayed or crimped, replace them. The throttle cable should be routed behind the bars for additional protection. A lot of riders carry a spare throttle cable as well. It can be taped to the one already in use and this makes changing over easy. Spare clutch and brake cables aren’t really necessary as the bike can be ridden without them in a pinch.

Dirt should be removed from under the rubber fork boots or sliders and fork seals should be replaced if they are leaking excessively. It’s a good idea to change fork oil periodically, also. Rear shocks require little maintenance, but the damper shafts should be inspected to see if they are straight.

Next check the wheels and tires. Knobby tires are best. They should be locked to the rims with either sheet metal screws or rim locks. All spokes should be checked for tightness and wired together where they intersect. This prevents further damage in the event spoke breakage occurs.

As far as the engine/transmission package goes, check the oil level in the transmission and waterproof the electrics and carburetor. Silicone sealant is one way to keep water out and it should be applied liberally to the spark plug lead and other wires at the high tension coil, and at the point where the wiring exits the engine case from the flywheel magneto, GDI unit, or whatever. Make doubly sure water and dirt cannot get into the carb via the control cables or a stuck slide may result.

Last, but equally important, Loctite and/or safety wire every nut and bolt on the bike. The object is to finish with everything in working order and attached to the bike.

Armed with the above information and a little luck, a finisher’s pin is not out of reach for any novice at the end of his first event. Exhaustion is practically guaranteed, though, and additional aches and pains on Monday morning may convince some—at least temporarily—never to ride an enduro again. In all probability, though, most will ride again and eventually trophies will be piling up in several newcomers’ dens. [Ô]