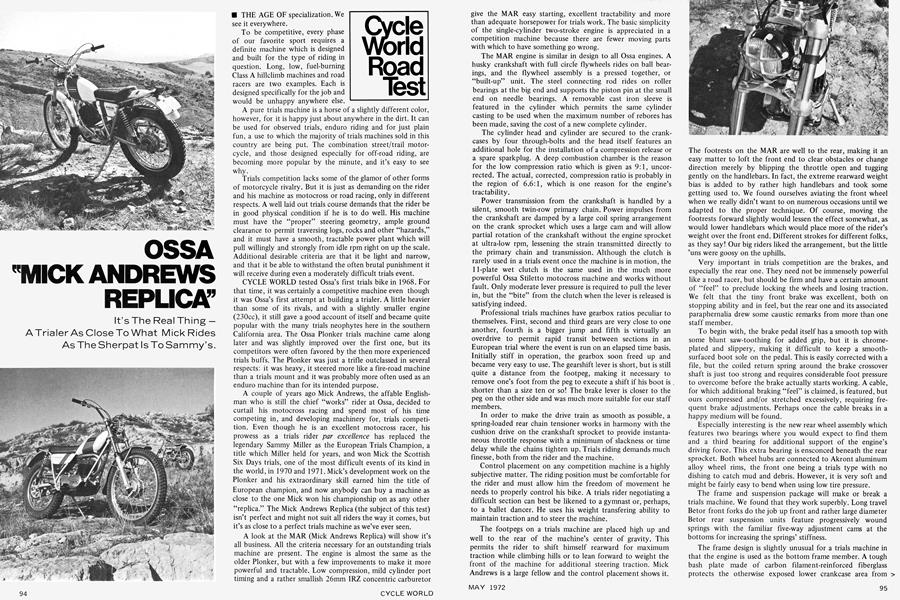

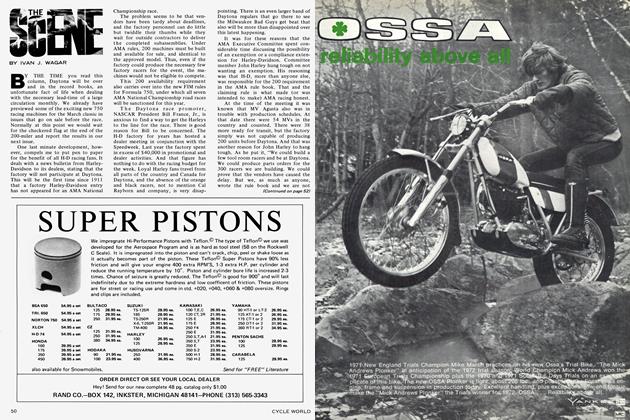

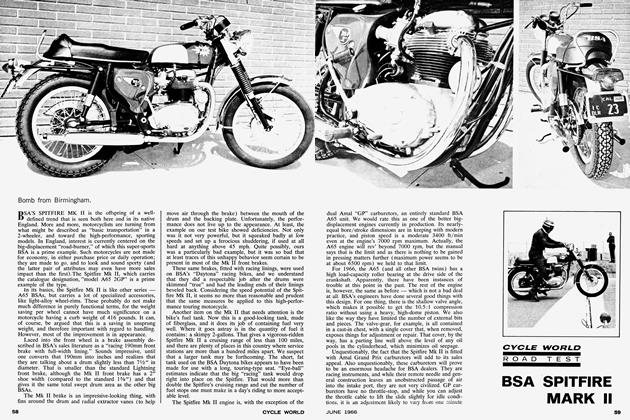

OSSA "MICK ANDREWS REPLICA"

Cycle World Road Test

It’s The Real Thing — A Trialer As Close To What Mick Rides As The Sherpat Is To Sammy’s.

THE AGE OF specialization. We see it everywhere.

To be competitive, every phase of our favorite sport requires a definite machine which is designed and built for the type of riding in question. Long, low, fuel-burning Class A hillclimb machines and road racers are two examples. Each is designed specifically for the job and would be unhappy anywhere else.

A pure trials machine is a horse of a slightly different color, however, for it is happy just about anywhere in the dirt. It can be used for observed trials, enduro riding and for just plain fun, a use to which the majority of trials machines sold in this country are being put. The combination street/trail motorcycle, and those designed especially for off-road riding, are becoming more popular by the minute, and it’s easy to see why.

Trials competition lacks some of the glamor of other forms of motorcycle rivalry. But it is just as demanding on the rider and his machine as motocross or road racing, only in different respects. A well laid out trials course demands that the rider be in good physical condition if he is to do well. His machine must have the “proper” steering geometry, ample ground clearance to permit traversing logs, rocks and other “hazards,” and it must have a smooth, tractable power plant which will pull willingly and strongly from idle rpm right on up the scale. Additional desirable criteria are that it be light and narrow, and that it be able to withstand the often brutal punishment it will receive during even a moderately difficult trials event.

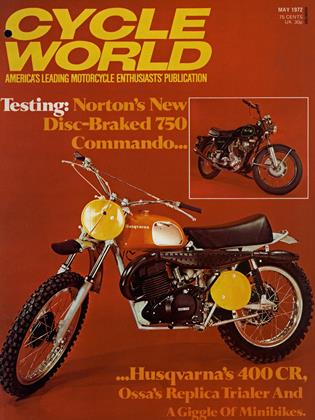

CYCLE WORLD tested Ossa’s first trials bike in 1968. For that time, it was certainly a competitive machine even though it was Ossa’s first attempt at building a trialer. A little heavier than some of its rivals, and with a slightly smaller engine (230cc), it still gave a good account of itself and became quite popular with the many trials neophytes here in the southern California area. The Ossa Plonker trials machine came along later and was slightly improved over the first one, but its competitors were often favored by the then more experienced trials buffs. The Plonker was just a trifle outclassed in several respects: it was heavy, it steered more like a fire-road machine than a trials mount and it was probably more often used as an enduro machine than for its intended purpose.

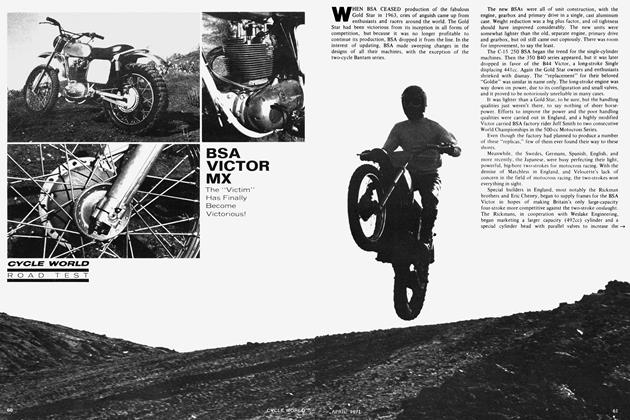

A couple of years ago Mick Andrews, the affable Englishman who is still the chief “works” rider at Ossa, decided to' curtail his motocross racing and spend most of his time competing in, and developing machinery for, trials competition. Even though he is an excellent motocross racer, his prowess as a trials rider par excellence has replaced the legendary Sammy Miller as the European Trials Champion, a title which Miller held for years, and won Mick the Scottish Six Days trials, one of the most difficult events of its kind in the world, in 1970 and 1971. Mick’s development work on the Plonker and his extraordinary skill earned him the title of European champion, and now anybody can buy a machine as close to the one Mick won his championship on as any other “replica.” The Mick Andrews Replica (the subject of this test) isn’t perfect and might not suit all riders the way it comes, but it’s as close to a perfect trials machine as we’ve ever seen.

A look at the MAR (Mick Andrews Replica) will show it’s all business. All the criteria necessary for an outstanding trials machine are present. The engine is almost the same as the older Plonker, but with a few improvements to make it more powerful and tractable. Low compression, mild cylinder port timing and a rather smallish 26mm IRZ concentric carburetor give the MAR easy starting, excellent tractability and more than adequate horsepower for trials work. The basic simplicity of the single-cylinder two-stroke engine is appreciated in a competition machine because there are fewer moving parts with which to have something go wrong.

The MAR engine is similar in design to all Ossa engines. A husky crankshaft with full circle flywheels rides on ball bearings, and the flywheel assembly is a pressed together, or “built-up” unit. The steel connecting rod rides on roller bearings at the big end and supports the piston pin at the small end on needle bearings. A removable cast iron sleeve is featured in the cylinder which permits the same cylinder casting to be used when the maximum number of rebores has been made, saving the cost of a new complete cylinder.

The cylinder head and cylinder are secured to the crankcases by four through-bolts and the head itself features an additional hole for the installation of a compression release or a spare sparkplug. A deep combustion chamber is the reason for the low compression ratio which is given as 9:1, uncorrected. The actual, corrected, compression ratio is probably in the region of 6.6:1, which is one reason for the engine’s tractability.

Power transmission from the crankshaft is handled by a silent, smooth twin-row primary chain. Power impulses from the crankshaft are damped by a large coil spring arrangement on the crank sprocket which uses a large cam and will allow partial rotation of the crankshaft without the engine sprocket at ultra-low rpm, lessening the strain transmitted directly to the primary chain and transmission. Although the clutch is rarely used in a trials event once the machine is in motion, the 11-plate wet clutch is the same used in the much more powerful Ossa Stiletto motocross machine and works without fault. Only moderate lever pressure is required to pull the lever in, but the “bite” from the clutch when the lever is released is satisfying indeed.

Professional trials machines have gearbox ratios peculiar to themselves. First, second and third gears are very close to one another, fourth is a bigger jump and fifth is virtually an overdrive to permit rapid transit between sections in an European trial where the event is run on an elapsed time basis. Initially stiff in operation, the gearbox soon freed up and became very easy to use. The gearshift lever is short, but is still quite a distance from the footpeg, making it necessary to remove one’s foot from the peg to execute a shift if his boot is shorter than a size ten or so! The brake lever is closer to the peg on the other side and was much more suitable for our staff members.

In order to make the drive train as smooth as possible, a spring-loaded rear chain tensioner works in harmony with the cushion drive on the crankshaft sprocket to provide instantaneous throttle response with a minimum of slackness or time delay while the chains tighten up. Trials riding demands much finesse, both from the rider and the machine.

Control placement on any competition machine is a highly subjective matter. The riding position must be comfortable for the rider and must allow him the freedom of movement he needs to properly control his bike. A trials rider negotiating a difficult section can best be likened to a gymnast or, perhaps, to a ballet dancer. He uses his weight transfering ability to maintain traction and to steer the machine.

The footpegs on a trials machine are placed high up and well to the rear of the machine’s center of gravity. This permits the rider to shift himself rearward for maximum traction while climbing hills or to lean forward to weight the front of the machine for additional steering traction. Mick Andrews is a large fellow and the control placement shows it.

The footrests on the MAR are well to the rear, making it an easy matter to loft the front end to clear obstacles or change direction merely by blipping the throttle open and tugging gently on the handlebars. In fact, the extreme rearward weight bias is added to by rather high handlebars and took some getting used to. We found ourselves aviating the front wheel when we really didn’t want to on numerous occasions until we adapted to the proper technique. Of course, moving the footrests forward slightly would lessen the effect somewhat, as would lower handlebars which would place more of the rider’s weight over the front end. Different strokes for different folks, as they say! Our big riders liked the arrangement, but the little ’uns were goosy on the uphills.

Very important in trials competition are the brakes, and especially the rear one. They need not be immensely powerful like a road racer, but should be firm and have a certain amount of “feel” to preclude locking the wheels and losing traction. We felt that the tiny front brake was excellent, both on stopping ability and in feel, but the rear one and its associated paraphernalia drew some caustic remarks from more than one staff member.

To begin with, the brake pedal itself has a smooth top with some blunt saw-toothing for added grip, but it is chromeplated and slippery, making it difficult to keep a smoothsurfaced boot sole on the pedal. This is easily corrected with a file, but the coiled return spring around the brake crossover shaft is just too strong and requires considerable foot pressure to overcome before the brake actually starts working. A cable, for which additional braking “feel” is claimed, is featured, but ours compressed and/or stretched excessively, requiring frequent brake adjustments. Perhaps once the cable breaks in a happy medium will be found.

Especially interesting is the new rear wheel assembly which features two bearings where you would expect to find them and a third bearing for additional support of the engine’s driving force. This extra bearing is ensconced beneath the rear sprocket. Both wheel hubs are connected to Akront aluminum alloy wheel rims, the front one being a trials type with no dishing to catch mud and debris. However, it is very soft and might be fairly easy to bend when using low tire pressure.

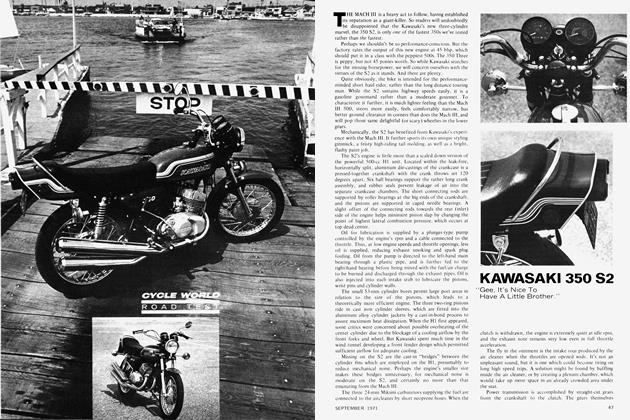

The frame and suspension package will make or break a trials machine. We found that they work superbly. Long travel Betor front forks do the job up front and rather large diameter Betor rear suspension units feature progressively wound springs with the familiar five-way adjustment cams at the bottoms for increasing the springs’ stiffness.

The frame design is slightly unusual for a trials machine in that the engine is used as the bottom frame member. A tough bash plate made of carbon filament-reinforced fiberglass protects the otherwise exposed lower crankcase area from damage by rocks. Steering head angle measures 26 deg., and the front fork rake is 28 d 0. This variance is achieved by different top and bottom triple-clamps, and is common practice on trials machines.

Frame construction and detailing is among the best we’ve ever seen, regardless of the machine’s origin. Welds are smoothly applied and what appears to be thin-walled tubing is used for the connecting members to keep weight down and yet maintain sufficient rigidity. The only weak point in the appearance department on the entire machine was the chrome-plated exhaust header pipe: the chrome began to blister and fall off in spots after a couple of hours of riding.

Lights on a trials machine? Well, not unless you really want them to make the machine “enduro legal.” Both the headlight and taillight are cleverly mounted in rubber which practically precludes breakage, and will be included with every MAR but not installed. There is even a horn under the seat, and not installing these items would reduce the already incredibly light weight of the MAR by a couple of pounds, making it the lightest 250 trials machine we have ever tested.

Nice touches abound. The immaculate fiberglass gas tank and side panels have pleasing shapes and fit properly. The green and white color scheme is most attractive, and the silver frame adds a touch of class. The speedometer which is required for European trials events is tucked in behind the left hand fork leg to prevent damage but will probably be removed by most American trials buffs. Almost every attempt has been made to pare precious ounces from the machine. Beautiful aluminum alloy clutch and brake lever clamps are secured to the handlebars with alien screws, Pirelli 2-ply trials tires are used, which are lighter and more supple than their 4-ply counterparts, and rubber accordian-type dust excluders are used on the ends of the clutch, front brake and rear brake cables.

No additional flywheel is used to smooth the power delivery but the Motoplat electronic ignition’s flywheel is larger and heavier than the one used on the Stiletto and gives good results. A healthy spark is provided even at cranking speed, aiding the starting chore, and sufficient power is available at any rpm over idle to burn the lights brightly.

The kickstand, which isn’t absolutely necessary, is well designed with a large “foot” at the end to prevent the stand from sinking into the ground and the machine falling over. It is well tucked in and out of the way, too.

Our gripe list is much shorter. We can’t understand why a couple of more cents wasn’t spent on elastic stop nuts here and there instead of conventional nuts and lockwashers. One works just about as well as the other, but the stopnuts are favored for aircraft use and are, we feel, worth the additional expense. A stopnut will stay on the bolt even if it hasn’t been tightened properly.

The kickstart lever is too long for easy cranking on a steep hillside (unless you’re over eight feet tall) which we had to do from time to time because of the carburetor’s propensity to flooding when the bike was leaned way over. Some fettling would undoubtedly cure this, and the slight “fluffiness” upon first opening the throttle could be cured by a carburetor slide with a slightly higher cutaway. Of course, each competition machine must be razor-tuned for the rider’s part of the country, so it’s really not fair to criticize.

In view of the exhaust’s silence (79 db with the chromeplated muffler in place) we felt that the intake roar was a little high, although acceptably low at less than full throttle.

The price isn’t what you could call cheap, but no really professional quality machine’s price is. Considering what you get, it’s worth every cent.

OSSA

$940