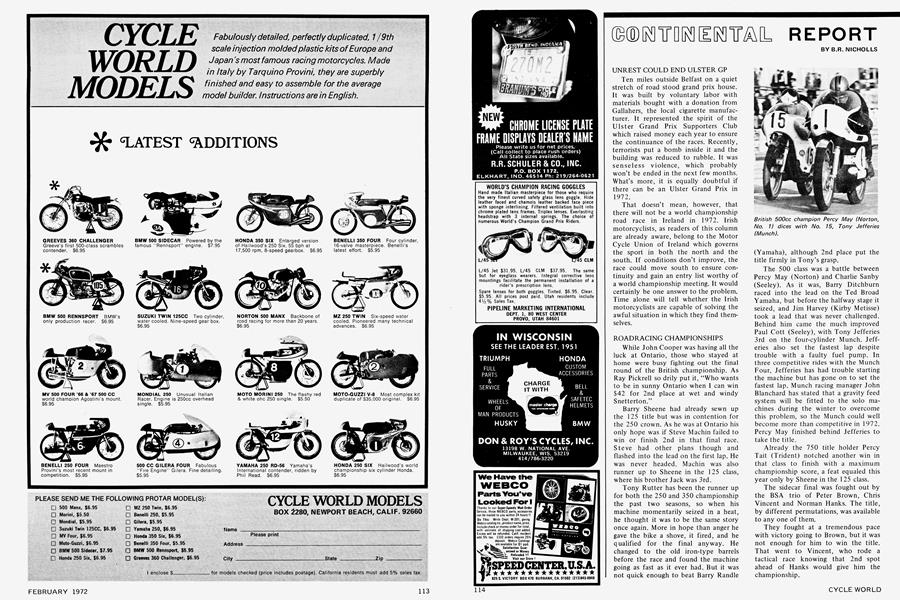

CONTINENTAL REPORT

UNREST COULD END ULSTER GP

B.R. NICHOLLS

Ten miles outside Belfast on a quiet stretch of road stood grand prix house. It was built by voluntary labor with materials bought with a donation from Gallahers, the local cigarette manufacturer. It represented the spirit of the Ulster Grand Prix Supporters Club which raised money each year to ensure the continuance of the races. Recently, terrorists put a bomb inside it and the building was reduced to rubble. It was senseless violence, which probably won’t be ended in the next few months. What’s more, it is equally doubtful if there can be an Ulster Grand Prix in 1972.

That doesn’t mean, however, that there will not be a world championship road race in Ireland in 1972. Irish motorcyclists, as readers of this column are already aware, belong to the Motor Cycle Union of Ireland which governs the sport in both the north and the south. If conditions don’t improve, the race could move south to ensure continuity and gain an entry list worthy of a world championship meeting. It would certainly be one answer to the problem. Time alone will tell whether the Irish motorcyclists are capable of solving the awful situation in which they find themselves.

ROADRACING CHAMPIONSHIPS

While John Cooper was having all the luck at Ontario, those who stayed at home were busy fighting out the final round of the British championship. As Ray Pickrell so drily put it, “Who wants to be in sunny Ontario when I can win $42 for 2nd place at wet and windy Snetterton.”

Barry Sheene had already sewn up the 125 title but was in contention for the 250 crown. As he was at Ontario his only hope was if Steve Machin failed to win or finish 2nd in that final race. Steve had other plans though and flashed into the lead on the first lap. He was never headed. Machin was also runner up to Sheene in the 125 class, where his brother Jack was 3rd.

Tony Rutter has been the runner up for both the 250 and 350 championship the past two seasons, so when his machine momentarily seized in a heat, he thought it was to be the same story once again. More in hope than anger he gave the bike a shove, it fired, and he qualified for the final anyway. He changed to the old iron-type barrels before the race and found the machine going as fast as it ever had. But it was not quick enough to beat Barry Randle (Yamaha), although 2nd place put the title firmly in Tony’s grasp.

The 500 class was a battle between Percy May (Norton) and Charlie Sanby (Seeley). As it was, Barry Ditchburn raced into the lead on the Ted Broad Yamaha, but before the halfway stage it seized, and Jim Harvey (Kirby Metisse) took a lead that was never challenged. Behind him came the much improved Paul Cott (Seeley), with Tony Jefferies 3rd on the four-cylinder Munch. Jefferies also set the fastest lap despite trouble with a faulty fuel pump. In three competitive rides with the Munch Four, Jefferies has had trouble starting the machine but has gone on to set the fastest lap. Munch racing manager John Blanchard has stated that a gravity feed system will be fitted to the solo machines during the winter to overcome this problem, so the Munch could well become more than competitive in 1972. Percy May finished behind Jefferies to take the title.

Already the 750 title holder Percy Tait (Trident) notched another win in that class to finish with a maximum championship score, a feat equaled this year only by Sheene in the 125 class.

The sidecar final was fought out by the BSA trio of Peter Brown, Chris Vincent and Norman Hanks. The title, by different permutations, was available to any one of them.

They fought at a tremendous pace with victory going to Brown, but it was not enough for him to win the title. That went to Vincent, who rode a tactical race knowing that 2nd spot ahead of Hanks would give him the championship.

One would have thought that at the end of such a meeting there would have been some sort of presentation to the title winners; not on your life. Not even a top ACU official was there that day. It’s a small wonder that the championships lack a sponsor. Riders seem to be the only ones showing any interest in the series at all. It seems to me that the only way to inject any life into these races at all is to do something drastic. This year the series was over seven meetings concerning a period of some seven months. The difficulty is to hold British championships that do not clash with classic grands prix. Perhaps it would be better to restrict it to four meetings and an up-to-350 champion and over-350 champion. Run races in the present classes of 125, 250 and 350 for the first group, and 400-5.00cc and up to lOOOcc for the second group. Riders could enter more than one class in their group and score points as at present. The champions would then be the ones with the most points in each class. Sidecars could fight it out in the present two classes of up to 500cc, and allcomers up to 1300cc. Then, if a sponsor could be found, it would only be necessary to finance three titles instead of the present six. Simplicity must be the key to a successful championship.

LACK OF RIDER CONSIDERATION

That is not something that the FIM agrees with though. The 1972 road race series will be contested over 14 meetings and will involve those competitors who wish to race all of them. Racing in all events will mean something like 10,000 miles of traveling. Worst hop of all is from the Isle of Man TT to Yugoslavia, some 2000 miles including two ferry crossings. From that meeting, riders will have to flog right back across Europe again for the Dutch meeting. Gas bills alone for those two journeys will be at least $300. Some riders will have to skip some meetings purely on economic grounds.

It only serves to emphasize criticism that the FIM could not care less about the riders; they have managed to arrange 12 meetings in 14 weeks and that includes the two necessary in the Isle of Man for the TT. The FIM is just waking up to the fact that riders must receive a better organized calendar of events both from grands prix organizers and from the FIM itself. This has been made quite clear by Henry Burik, Dutch president of the FIM’s Sporting Commission. More men like Burik at the top are in order, and less of those with the pompous, aloof attitude that FIM President Nicolas Rodil del Valle displays in refusing to have anything to do with the Grand Prix Riders Association, which is struggling to attain some sort of status for grand prix riders. The authority in some cases seems to forget that to have racing one needs racers.

(Continued on page 116)

Continued from page 115

U.S. IS MAKING ITS MARK

Already the United States is making its mark within the FIM; the best piece of news from the Congress was that the 1973 International Six Days Trial will be held in U.S.A.

The other point was the adoption of an international Formula 750 class. It was put forward by the British representative but is based on the American concept of racing. Having seen road racing at Daytona, I look forward to 1973 Six Days.

You may be interested to learn that it has at last been decided the British team can no longer go on competing in that event on the good old four-stroke Triumph Twin. There is little doubt that the 1972 team will be mounted on two-stroke machinery, as the Spanish Ossa concern has made a generous offer of six free machines plus mechanics for our Trophy team. With it now being obligatory for machinery to represent three separate classes the Ossa would be of 175, 250 and 255cc displacement. It is difficult to see how such an offer can be refused, especially when the 1971 British Vase B team were all Ossamounted and finished with a clean sheet.

They were mounted on 250-ec models, one of which I recently rode when covering the Scott Trial in Yorkshire. It was all that one could ask a Six Days mount to be. The five-speed gearbox is absolutely ideal, offering tremendous acceleration and a top speed in the region of 90 mph. For anyone wanting something not quite so furious, the 175-cc model should be an ideal mount.

SCOTT TRIAL TO RATHMELL

The Scott Trial is a classic one-day trial run over the rough terrain of north Yorkshire. Not only is it observed with riders losing marks in sections, but it is also against the clock. Riders, therefore, have to try and strike that happy blend between pressing on and yet retaining their edge when an observed section is reached. Marks lost on time are one for every two minutes after standard time, which is that set by the fastest competitor.

It is possible for one man to set fastest time and be best on observation, in which case he would take the top three awards. No such thing happened this year though.

Alan Lampkin (Bultaco) stormed round the course to set standard time, losing 102 marks on observation in the process. Brilliant 18-year-old Robert Shepherd (Montesa) suffered a puncture and further delays, so decided to take care on the observed sections. He was best on observation with 76 marks lost, but a further 32 on time dropped him to 6th place.

The man who struck the right blend was Malcolm Rathmell (Bultaco). His 83 on observation plus 1 on time gave him an eight-mark advantage over fellow Yorkshire man Bill Wilkinson (Ossa). Then came one of those incredible ties between three men for 3rd place. It was decided that the rider who progressed furthest round the course observed sections without penalty would win. Gordon Farley (Montesa) came out best, with Rob Edwards (Montesa) 4th, and standard time-setter Alan Lampkin 5th.

As a result of his 3rd place, Farley retains the British championship he won last year. Sammy Miller previously held the title for 11 consecutive years; with maestro Sam out of the way, competition for the title is much tougher. The frail looking figure of tall, thin Farley belies his undoubted ability, and I do not think he has reached his peak yet. This 2nd championship will give him renewed confidence. Though he may well fail in his attempt to become the British Experts’ trial winner next month, he could realize his ambition in 1972.

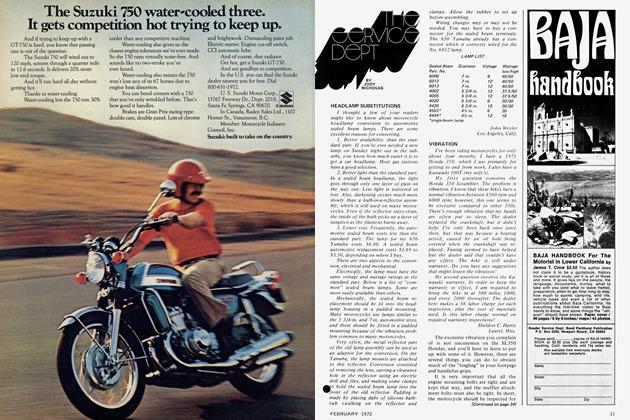

WORLD SPEEDWAY CHAMPION

One man who is brimful of confidence at the moment is world speedway champion Ole Olsen from Denmark. Not only is he an ace on the cinders, but he can also rush a grass track machine round with equal brilliance, as he showed at Lydden.

The Lydden circuit is difficult, as it is part grass, part loose chalk dust and part highly polished chalk. Whether he gated well or not made no difference to the dashing Dane who won every race he contested.

At 24, Denmark’s first world champion obviously has many years of top class riding in front of him. His determination and skill enable him to come from the back and ride round men like thrice-world champion Ivan Mauger, whom he dethroned.