EUROPEAN TOURING

A GUIDE TO GET YOU STARTED

STEPHEN J. HERZOG

WHO CAN BLAME me for being a little nervous? My home was in California, and there I was half-way around the world in London about to begin a 3000-mile trip across Europe, with what amounted to 30 minutes of motorcycling experience, a list of equipment meant for a two-day stay in the woods, a dictionary, and a helmet. It was insane.

But still I managed to survive for 28 days, learned how to ride the motorcycle, and even enjoyed the trip enough to want to return again the next summer. For that second trip in 1969 I bought a map of Scandinavia and headed off into the Land of the Midnight Sun for eight weeks and 7000 miles of trees and reindeer. And you can be sure I’d be back again this year if it weren’t for the draft.

I know many other students though who aren’t stranded and would like to get a motorcycle and spend their summer touring Europe. Getting started is the biggest problem for most of these people, in that they don’t know where to begin planning for such a trip. While many can’t base their upcoming trips on previous experience, it’s not necessary, for much of the basic information can easily be given in a magazine. The addresses of a few good European dealers, equipment recommendations, an idea of where I could eat and sleep cheaply—had I known these before I left in 1968 I could have saved myself a lot of trouble.

If the idea of touring Europe appeals to you, but you feel you could use a bit more information, this article may help you. In the following I will explain how I went about planning my trips with the intention of giving you some concrete facts to begin working with. The way I toured is not the only way to see Europe, but I learned many things which worked quite well for me and should at least give you a place to start.

The first thing to begin thinking about is buying a motorcycle. Several thousand miles of touring are hard on any cycle and the one you choose should be chosen primarily on the basis of its reputation for reliability. Speed should definitely be a secondary consideration. If you can afford a motorcycle which combines the two, fine, but it’s not a good idea to buy for speed alone, at the risk of losing long term dependability. Even the slowest, but still working, motorcycle is faster than a superfast multi, being pushed.

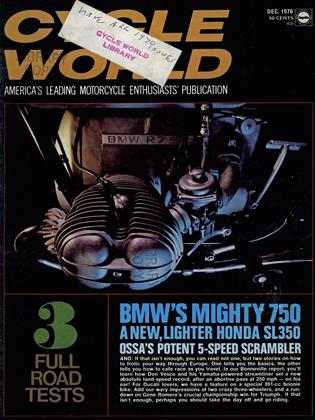

Europe produces many fast, and still reliable, motorcycles, BMWs being about the best compromise for touring. Their larger models are easily capable of the 70-mph-plus speeds found on the German autobahns (where, by the way, there is no speed limit) and yet are as reliable as any large bike made. BMWs are quite common everywhere except the British Isles, and not only do many civilians own them, but BMWs are used by the great majority of Europe’s police. Because there are so many on the road, it’s no problem to have them repaired, should something go wrong. While not on every corner, BMW repair shops are more easily found than those of any other make. But it is still a fact that, in Europe as in the U.S., BMWs are not a cheap motorcycle, and it was the price tag alone which kept me from buying one. Triumph was my second choice.

Triumphs are an especially good motorcycle to buy in Europe because not only are they reliable, but compared to U.S. prices, they’re cheap. Their service facilities are fairly extensive, though not as complete as BMW’s. Because all my European touring has been done on Triumphs, what information I give here will be dealing most specifically with them.

When buying any type of motorcycle for use in Europe, the simplest way to get information is by writing directly to the manufacturer. I wrote to Triumph, Coventry, in 1968, and they sent me the address of a British dealer whom I could then buy the motorcycle from. Some manufacturers have a system whereby you can order the motorcycle and complete all the insurance forms, etc., through your local dealer in the U.S. and arrange to pick it up in Europe. I preferred to work directly with the British dealer because I felt more certain that he knew exactly what I wanted.

The great number of Americans who arrive in England wanting motorcycles make the summer months the busiest for British dealers. For the American buyer this bottleneck situation creates several problems:

The English have a tax similar to our sales tax, which they must pay on almost everything they buy. This “purchase tax” is high, amounting to about 25 percent on motorcycles. But as foreigners, we Americans can have this tax waived for one year on the condition that the motorcycle leaves Great Britain permanently within that time. This waiver applies only to those motorcycles which have been earmarked for export, and not to domestic models sold in England to the English. If, for instance, you went into a British motorcycle shop not having ordered a cycle beforehand and asked to buy a new Triumph, two things might happen. You could be lucky enough to find an export model in stock and therefore avoid having to pay the purchase tax; or, if there were no export models in stock at any of the dealers’ (a good possibility in the summer) you could be forced to buy the domestic model and pay the tax, which on a Triumph Tiger 650 amounts to $219. Having to spend that much money when you hadn’t planned on it could easily cripple your trip, so it is best to place your order as far in advance as possible for the model you want. This way you’ll be sure of what you’re getting before you leave the U.S., and know it will be ready when you arrive in Europe.

The differences between the British domestic and export model motorcycles are important to the American buyer. Triumphs vary in a number of ways, the most obvious being the taillights. On the export models, such as those sold in the U.S., the taillight housing is cast metal; on the British “home market” model it is simply formed sheet metal. For Americans this one difference is important because the flimsier domestic taillights do not meet U.S. federal safety requirements.

As you can see from the way British law works, it doesn’t pay for the American to wait until reaching England to begin looking for a motorcycle. Ordering in advance is really the only way to be sure of getting what you want. However, if you are buying a used machine over there, you’ll have no such problems; you must only have a good eye.

If a Triumph is the motorcycle you want, and you need the address of a British dealer to place an order with, this is the dealership I bought from both times: Hughes, 114 Manor Road, Wallington, Surrey, England. Besides the great job they did of setting up my motorcycle, I was most impressed by the fact that Hughes took the time to answer any questions I had and were very willing to help me with some of my special requirements. The town of Wallington is a suburb of London and can be reached in about 30 minutes from London’s huge Victoria train station.

One important thing to keep in mind no matter which make of motorcycle you decide to buy is that British prices do not vary from dealer to dealer, but are the same everywhere. A new Bonneville, for example, will cost $884 whether bought from Hughes or any of the other British dealers. While Hughes sells only Triumphs, larger dealerships such as Elite and Harvey Owen have other makes available. You might write them for information on BSA, Norton, or whatever. The addresses of these two dealers are: Elite Motors (Tooting) Ltd., 844-965 Garratt Lane, Tooting Broadway, London, SW 17; Harvey Owen, 181-183 Walworth Road, London, SE 17. If you’re buying a used bike, the London area is the best in Britain for your searches.

Liability insurance coverage is the only thing, besides your passport, that you can be sure will be checked at every border crossing in Europe and Scandinavia. You must have it. European insurance rates for motorcycles are fairly uniform, and to give you an idea of what you can expect to pay I’ll quote some figures from what Hughes offers. For liability, fire, and theft: 1 month$41; 2 months-$55; 3 months-$71. Without the theft coverage the rates are about 20 percent less.

To help border guards check your insurance coverage, the Europeans have adopted a special standardized form which gives the dates during which your insurance is valid. If you were to arrive at a border crossing with insurance papers other than this special International Motor Insurance Card, or “green card,” the border guards probably wouldn’t understand what the papers were (ever tried explaining “insurance” in Swedish?) and could even keep you from entering their country. If you are planning to obtain your insurance in the U.S. before you leave, save yourself problems in Europe and have it verified beforehand on the green card. Insurance bought in Europe is automatically given with a green card.

For those of you buying your motorcycle in England, the registration cost is very reasonable. It’s free. This is a new system, for when I bought my motorcycle, I paid $12 for registration and “road tax.” But, beginning in 1970, there will be no charge to foreigners for one year after date of purchase. There is no need to worry about using the British plates you receive in other countries, for they are quite valid internationally.

The above information is a basic rundown of what’s involved in buying a motorcycle in Europe, but if you’re really serious about touring you’ll need other, more specific details, in order to meet your own requirements. Now is the time to begin writing letters to the various European dealers and manufacturers. They’ll answer any questions you might have and send all the necessary order forms.

Whichever motorcycle you do order, some attention should be given to making it as functional as possible to meet the demands of long distance touring. In 1969 the motorcycle I bought was the standard 500-cc Triumph TIOOC, but for the trip, I made the following changes and additions: a larger gas tank, tachometer, windshield, and panniers (saddlebags). Nothing drastic, but each definitely helped make the trip both more comfortable and easier to manage.

My reasons for choosing the TIOOC were basically four. First, when compared to the Triumph 250 I had the first summer, the T100C was faster and had better high speed acceleration for passing the many trucks 1 encountered while touring. Also, it was more capable of going for hours at 70 mph loaded down with all my equipment. Second, with 60 lb. of gear it was not so top-heavy a cycle to handle, as any 650 would have been with its higher engine weight. Third, unlike the 500-cc Daytona, the TIOOC has only one carburetor, which means better gas mileage and fewer problems keeping the carburetor tuned for both cylinders. And fourth, the TIOOC costs $65 less than the Daytona and $120 less than the cheapest Triumph 650.

I had run out of gas once in 1968, and knew I didn’t want to tempt fate again in 1969 with the TIOOC’s small (for touring) 2.5-gal. tank. 1 found it was possible to have a larger tank mounted and promptly bought one with a 3.5-gal. capacity. Aside from being able to travel further without stopping, I no longer was subject to the difficulties I’d faced in Northern Scandinavia, where gas stations were rare and many of the main roads were so poor that first and second gears were all I could use for many hours at a time. Had I kept the smaller tank, these factors would have added up to my pushing the motorcycle at least twice. Even if you never need it, that feeling of security the larger tank alone brings is worth the effort of having one installed.

If you should do as I did and order a motorcycle which doesn’t come equipped with a tachometer, I think it would be worth the $18 cost to have one installed. When I bought the TIOOC, I was at first unfamiliar with its speed/rpm ratios, and to help me shift the tight new cycle more accurately I added a tachometer in addition to the speedometer. Not only did the tach help me break in the engine properly, but it also gave me something visual to shift by in the mountains when my ears were so plugged I couldn’t hear the engine. When I spend $600 for a motorcycle, I feel it’s only good policy to spend a little more and insure the health of the all important engine.

You’ll find too, that in all European countries except Great Britain the kilometer is used instead of the mile. To save yourself the trouble of having to constantly compute your speedometer’s miles/hour into kilometers/hour, just take a grease pencil or crayon and write the equivalent klm/hr over the mph markings. Its simple, but it works.

In 1968 it was my body alone which fought the wind, the rain, the bugs, and the hail; the next year 1 got smart and bought a windshield, letting it battle the elements while I relaxed and enjoyed the trip.

Simply stated, that is my whole argument for buying a windshield. Touring Europe is a different game altogether from a trip to the store or a few miles on the freeway, and while a windshield may be ugly and ruin the beautiful lines of the new motorcycle, it does help you, the rider, and for the sake of comfort should be considered. Bracing yourself against the wind for eight hours is tiring enough, but when a bee or a drop of rain smashes into your face at 60 mph day after day, the idea of a little protection might appeal to you. For the short distance riding I do in the U.S., I see no real purpose in having a windshield; but, in large part because of that $14 windshield, my second trip through Europe wasn’t an endurance test as it was in 1968.

The one real luxury I allowed myself was the saddlebags. Because I had a few cameras I wanted to keep dry, I thought these fiberglass “panniers” would be well worth their $50 cost. They were. In addition to being watertight, the panniers keep the weight of the equipment low, which helps handling because of the lowered center of gravity. I proved to myself that they were well made when, on the first day of my 1969 trip,

I dropped the cycle at 40 mph and lost only a little paint off the pannier. They have a lock, which makes it possible to leave some of your equipment on the motorcycle and not have to carry it all inside every night and repack it again the next morning. I bought my panniers from Hughes, but information can also be obtained by writing to the manufacturer: Craven Equipment, 61 Eden

Grove, London, N 7.

If you are planning to strap a suitcase to the motorcycle, the steel carrier for the Craven pannier boxes is a good mounting platform in itself and costs only $10. If you’d like to get the whole pannier set-up, it would be a good idea to use a disposable suitcase, or a cardboard box, to get your equipment from the U.S. to Europe. This way you won’t have to worry about where to store a good suitcase during your trip; when the trip is over just remove the pannier boxes and use them as “suitcases” to bring your gear home.

Unless you are taking a trailer, I think it is safe to assume that your motorcycle won’t have unlimited luggage space. Now the problem becomes one of planning what equipment will be used enough to warrant taking, and what will just waste valuable space. On a twoor three-month trip even the smallest mistakes in planning can leave you suffering for weeks, and it would therefore be to your advantage to think carefully before you leave and decide what your requirements are going to be.

What clothing and other personal articles you take are largely dependent on what you already own, where you’ll be going, and how important comfort is to you. I learned my lesson the first summer; clothing, etc. was important and made a big difference in whether or not I enjoyed the trip to its fullest. Based on the mistakes I made in 1968, I reorganized my equipment in 1969. The following is this “new improved list” and a few reasons why I chose what I did.

Blue denim Levis. They’re tough and look cleaner longer. Buy your riding pants a few inches longer than normal, because when you’re sitting on the cycle, any pants will ride up a few inches and a shorter pair will let a nice, cool breeze blow up your leg.

Razor. Shaving in Europe can become a problem for several reasons. First, a problem arises with an electric razor, in that the electrical current in Europe is 220V and not 117V as in the U.S. Second, American plugs won’t fit European sockets, so an adapter is needed. And third, in some of the more isolated areas electricity is not always available for shaving. I used a simple blade razor: it’s smaller, the used blades can be thrown away, and water is always obtainable for shaving.

Shoes. In addition to my high topped riding boots, I took a pair of sandals. They are common in Europe, fold flat when packed, and are nice to have when riding boots get wet.

Waterproof riding suit. In 1968, even though I had a good leather jacket and waterproof parka, I still froze. To solve the problem of keeping warm and dry, I invested in a Barbour International Suit. It is a waterproof, lined, cloth outfit which has both jacket and pants, many large pockets—and is warm. The collar, sleeves, pants, and waist can all be pulled tight to keep out the cold air. Another choice is the two-piece Black Knight rubber rain suit, which you can wear over street clothing and is absolutely hurricane-proof. Buy these items at the dealer’s or from D. Lewis, 124 Great Portland Street, London W 1. Lewis has just about everything you could want in the way of motorcycle clothing and rain gear. These special suits are particularly useful, if you can’t stand riding with a windshield.

The other equipment which I took, but which needs no explanation, was: windbreaker, short-sleeved sweatshirt, five pairs of underwear and T-shirts, four pairs of socks, shoelaces, metal mirror, shaving cream, bar soap and container, towel and washcloth, shampoo, sewing kit, small flashlight, unbreakable sunglasses, safety pins, extra buttons, insect repellent, Chapstick, full coverage helmet and visor, and lined leather gloves.

Europeans use about the same clothing and toilet articles as we do in America, so if you arrive in Europe and find you’ve forgotten a few things, don’t worry, because you’ll be able to buy them there. Also, with an airline weight allowance of only 44 lb., it might be necessary to wait and buy in Europe anyway, or risk having to pay the rather steep overweight charges on your luggage.

To carry what equipment wouldn’t fit in the panniers, in London I bought a waterproof “rucksack,” or pack, which I just tied onto the seat in back of me. This arrangement gave me something to lean against and made the going much easier for my back.

One last point on equipment: buy your helmet in the U.S. before you leave. Many European helmets are just plain dangerous to wear, and I know I wouldn’t want to trust my head to one.

In America a two-month trip can easily cost hundreds of dollars, especially if the tourist wants to sleep in a bed. When a motel room costs at least $6 per night, it is no wonder so many Americans prefer to spend their vacations at home watching TV. Europeans, on the other hand, have developed a system which lets them travel without going into debt for years. This solution is the International Youth Hostel Federation, which is basically a world wide system of dormitory-type accommodations which, in Europe, give the tourist a bed for as little as 37 cents in Germany to as much as 75 cents in Sweden. In a word, cheap!

Youth hostels are difficult to describe because no two hostels are alike. Schools are often converted into hostels during the summer months simply by moving the desks out and the beds in. Other hostels are converted homes, while some are beautiful new buildings designed especially for that purpose. But though each is unique, they do follow a basic pattern. Most have the standard dormitory layout with 8-10 beds per room, a common bathroom, and a large dining room. Some of the more primitive hostels are lacking in hot water, and even cold showers are unavailable in the more remote areas. All have some sort of kitchen arrangement where you can cook your own meals, while a few offer home-cooked meals for about 75 cents. As to availability, they are quite common, especially in Germany where there seems to be one in almost every town. Moving further from Germany they thin out to where in Northern Scandinavia they are rare, but not impossible to reach in a few hours. In Central and Southern Europe most hostelers are either hitch-hiking or on bicycles, so the hostels are seldom more than 50 miles apart —an easy distance for a motorcycle.

In 1968 I spent less than $20 to sleép in youth hostels in four weeks, and though its true that they are not Hilton Hotels, the youth hostel system more than accomplishes its aim-providing a cheap place to sleep. And it’s a good way to meet groovy people, male and female, or even find a riding partnermale or female.

Before using the hostels, you must first buy a membership card. All cards are valid for one year, but the cost varies depending on your age. If you are 17 or younger, the cost is $4; 18-20 years, $6; and 21 or over, $7. There is no age limit, but during the summer the hostelers are almost 100 percent students. In the U.S. the membership cards can be bought by writing to: American Youth Hostels, Inc., National Headquarters, 20 West 17th Street, New York, N.Y. 10011. AYH will send you an application and all the necessary information, but if you’re in a hurry, you can wait until you’re in Europe to buy the card at some, but not all, European hostels. If you have the time, it’s better to play it safe and get the card before you leave.

In case you were wondering, the hostels are co-ed except for the sleeping and bathroom areas. And believe me, there are enough girls using the hostels to keep it interesting.

If the hostels don’t appeal to you, there are, as everywhere, hotels. Their prices begin at about the $3-per-night range, but for about the same amount of money I think a better arrangement would be to stay in some of the private homes which rent rooms to tourists. I regret now that I didn’t use these more, because they are such a good way to see how other peoples live. These rooms can be found easily by the little signs put out along the side of the road, which read “bed and breakfast” in England and “zimmer” (room) in the German speaking areas.

A book which specializes in hotels is the famous Europe on $5 a Day, by Arthur Frommer. It explains in detail the hotel, eating, and sightseeing situation in the larger European cities, giving addresses for the good, but still cheap, hotels and restaurants. I put the book to good use while sightseeing. Because most tourists use the hotels, there are many similar “hotel books” available in the U.S., so you’ll have no trouble finding information.

Thanks to the fact that Europeans love to eat well, there are many restaurants and cafes in which the food is generally quite good and relatively cheap. When I was on the road and wearing my functional, though not dining quality, riding gear, I found it both cheaper and less hassle to just stop at a grocery store and buy some bread, cheese, milk, or whatever. That way I could either eat the food there or take it with me, but didn’t feel uncomfortable because of the way I was dressed.

Once you arrive in Europe and start your trip, I’m sure you’ll find, as I did, that touring Europe is not that much different than touring in the U.S. As with any trip though, the biggest problems are those you have before you begin, not the ones you have once you’re on your way. Planning is the key; and, as you can see, many of the problems can be taken care of before you leave home. If you do a good job of planning here in the U.S., all there will be left for you to do in Europe is enjoy the trip, which is really what it’s all about.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

December 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

December 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

December 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Features

FeaturesAnd Now...The Case For Traveling Light

December 1970 By Dan Hunt -

Competition

CompetitionThe Sacramento Mile

December 1970 By Dan Hunt