Four Valves For The Manx

CHARLIE ROUS

THE MOST FAMOUS of all racing machines must be the British Manx Norton. It will go down in motorcycling history as the machine that would not die; although it might have been better if the Manx Norton had not been so successful over the years since its first appearance in 1927, for its continued development undoubtedly stopped Britain from producing multi-cylindered machines so necessary for dominance of the world market today.

No new Manx Nortons have been produced since 1 961, although manufacturing rights were taken over to produce spares and new machines in 1970. But enthusiastic private engineers continue to develop more power to keep the old machines competitive in racing. Such private development in England has now taken the biggest-ever step to modernize t lie 5 00-ce Manx Norton and will surely make it the fastest single-cylinder racing machine in the world!

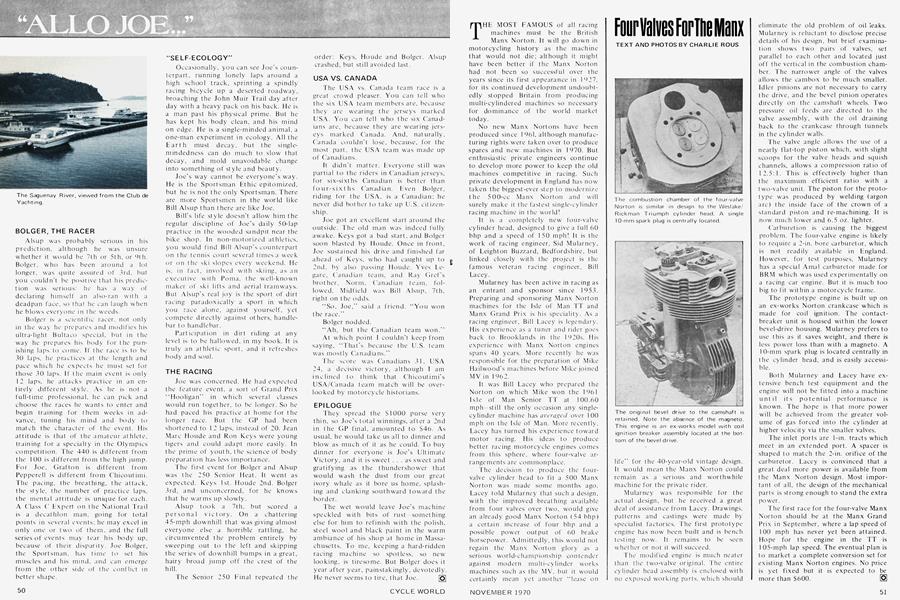

It is a completely new four-valve cylinder head, designed to give a full 60 bhp and a speed of 150 mph! It is the work of racing engineer, Sid Mularney, of Leighton Buzzard, Bedfordshire, but linked closely with the project is the famous veteran racing engineer, Bill Lacey.

Mularney has been active in racing as an entrant and sponsor since 1953. Preparing and sponsoring Manx Norton machines for the Isle of Man TT and Manx Grand Prix is his speciality. As a racing engineer. Bill Lacey is legendary. His experience as a tuner and rider goes back to Brook lands in the 19 20s. His experience with Manx Norton engines spans 40 years. More recently he was responsible for the preparation of Mike Hailwood’s machines before Mike joined M V in 1 962.

It was Bill Lacey who prepared the Norton on which Mike won the 1961 Isle of Man Senior TT at 100.60 mph—still the only occasion any singlecylinder machine has averaged over 100 mph on the Isle of Man. More recently, Lacey has turned his experience toward motor racing. His ideas to produce better racing motorcycle engines comes from this sphere, where four-valve arrangements are commonplace.

The decision to produce the fourvalve cylinder head to fit a 500 Manx Norton was made some months ago. Lacey told Mularney that such a design, with the improved breathing available from four valves over two, would give an already good Manx Norton (54 bhp) a certain increase of four bhp and a possible power output of 60 brake horsepower. Admittedly, this would not regain the Manx Norton glory as a serious world-championship contender against modern multi-cylinder works machines such as the MV. but it would certainly mean yet another “lease on life" for the 40-year-old vintage design. It would mean the Manx Norton could remain as a serious and worthwhile machine for the private rider.

Mularney was responsible for the actual design, but he received a great deal of assistance from Lacey. Drawings, patterns and castings were made by specialist factories. The first prototype engine has now been built and is bench testing now. It remains to be seen whether or not it will succeed.

The modified engine is much neater than the two-valve original. The entire cylinder head assembly is enclosed with no exposed working parts, which should eliminate the old problem of oil leaks. Mularney is reluctant to disclose precise details of his design, but brief examination shows two pairs of valves, set parallel to each other and located just off the vertical in the combustion chamber. The narrower angle of the valves allows the cambox to be much smaller. Idler pinions are not necessary to carry the drive, and the bevel pinion operates directly on the camshaft wheels. Two pressure oil feeds are directed to the valve assembly, with the oil draining back to the crankcase through tunnels in the cylinder walls.

The valve angle allows the use of a nearly flat-top piston which, with slight scoops for the valve heads and squish channels, allows a compression ratio of 12.5:1. This is effectively higher than the maximum efficient ratio with a two-valve unit. The piston for the prototype was produced by welding (argon arc) the inside face of the crown of a standard piston and re-machining. It is now much lower and 6.5 oz. lighter.

('arburetion is causing the biggest problem. The four-valve engine is likely to require a 2-in. bore carburetor, which is not readily available in England. However, for test purposes, Mularney has a special A mal carburetor made for BRM which was used experimentally on a racing car engine. But it is much too big to fit within a motorcycle frame.

The prototype engine is built up on an ex-works Norton crankcase which is made for coil ignition. The contactbreaker unit is housed within the lower bevel-drive housing. Mularney prefers to use this as it saves weight, and there is less power loss than with a magneto. A 10-mm spark plug is located centrally in the cylinder head, and is easily accessible.

Both Mularney and Lacey have extensive bench test equipment and the engine will not be fitted into a machine until its potential performance is known. The hope is that more power will be achieved from the greater volume of gas forced into the cylinder at higher velocity via the smaller valves.

The inlet ports are 1-in. tracts which meet in an extended port. A spacer is shaped to match the 2-in. orifice of the carburetor. Lacey is convinced that a great deal more power is available from the Manx Norton design. Most important of all, the design of the mechanical parts is strong enough to stand the extra power.

The first race for the four-valve Manx Norton should be at the Manx Grand Prix in September, where a lap speed of 100 mph has never yet been attained. Hope for the engine in the TT is 105-mph lap speed. The eventual plan is to market a complete conversion set for existing Manx Norton engines. No price is yet fixed but it is expected to be more than S600. [O]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

November 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

November 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

November 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

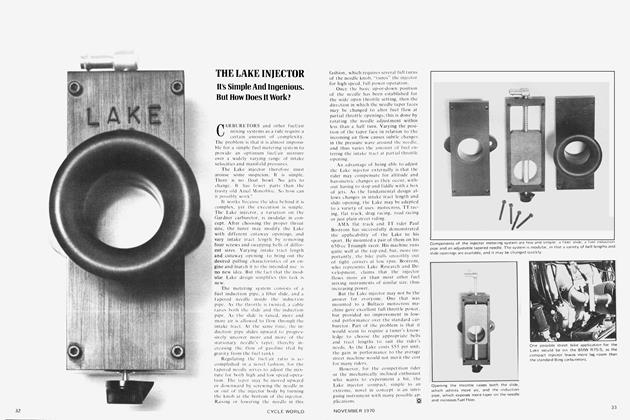

Technical, Etc.

Technical, Etc.The Lake Injector

November 1970 -

Features

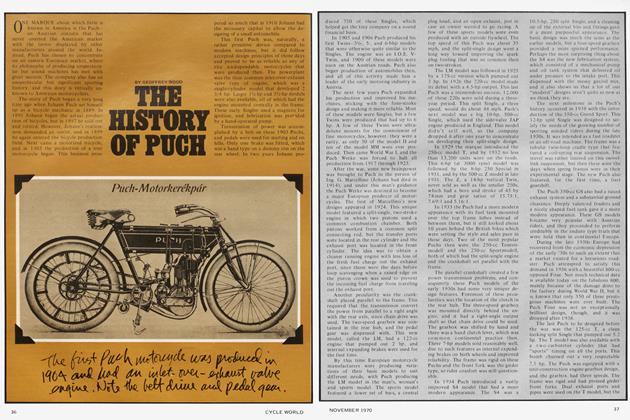

FeaturesThe History of Puch

November 1970 By Geoffrey Wood