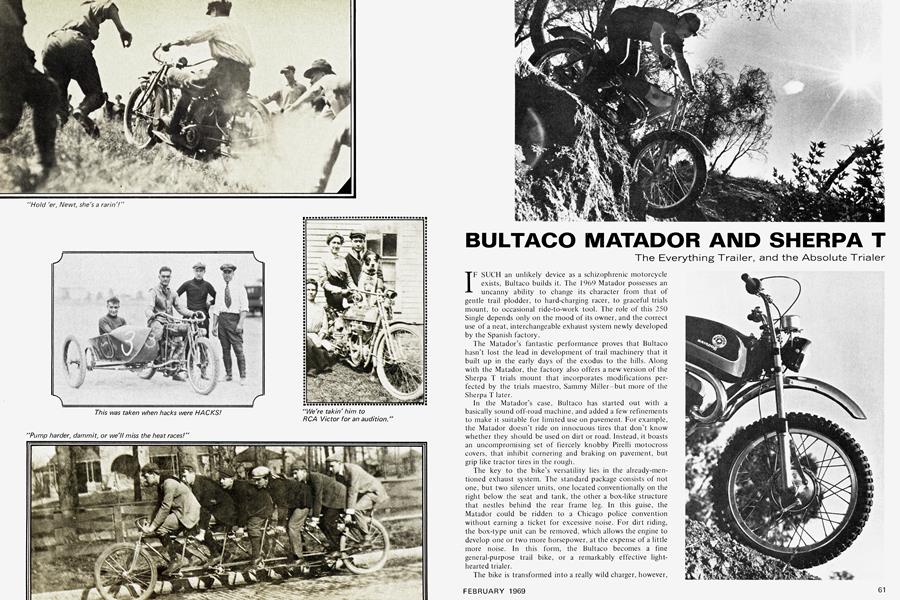

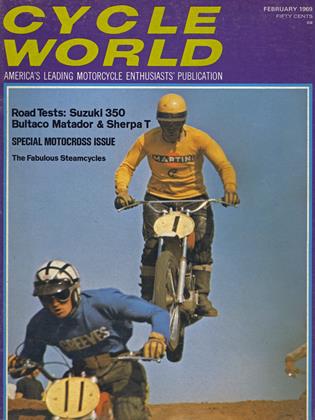

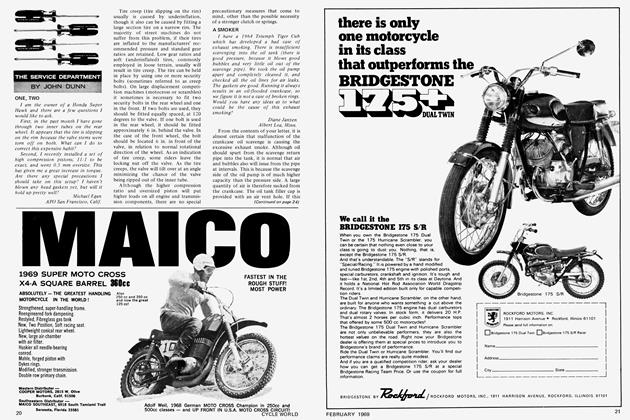

BULTACO MATADOR AND SHERPA T

The Everything Trailer, and the Absolute Trialer

IF SUCH an unlikely device as a schizophrenic motorcycle exists, Bultaco builds it. The 1969 Matador possesses an uncanny ability to change its character from that of gentle trail plodder, to hard-charging racer, to graceful trials mount, to occasional ride-to-work tool. The role of this 250 Single depends only on the mood of its owner, and the correct use of a neat, interchangeable exhaust system newly developed by the Spanish factory.

The Matador's fantastic performance proves that Bultaco hasn't lost the lead in development of trail machinery that it built up in the early days of the exodus to the hills. Along with the Matador, the factory also offers a new version of the Sherpa T trials mount that incorporates modifications per fected by the trials maestro, Sammy Miller-but more of the Sherpa T later.

In the Matador's case, Bultaco has started out with a basically sound off-road machine, and added a few refinements to make it suitable for limited use on pavement. For example, the Matador doesn't ride on innocuous tires that don't know whether they should be used on dirt or road. Instead, it boasts an uncompromising set of fiercely knobby Pirelli motocross covers, that inhibit cornering and braking on pavement, but grip like tractor tires in the rough.

The key to the bike's versatility lies in the already-men tioned exhaust system. The standard package consists of not one, but two silencer units, one located conventionally on the right below the seat and tank, the other a box-like structure that nestles behind the rear frame leg. In this guise, the Matador could be ridden to a Chicago police convention without earning a ticket for excessive noise. For dirt riding, the box-type unit can be removed, which allows the engine to develop one or two more horsepower, at the expense of a little more noise. In this form, the Bultaco becomes a fine general-purpose trail bike, or a remarkably effective light hearted trialer.

The bike is transformed into a really wild charger, however,

when the Stage 111 system is bolted on. This consists of an enduro-type expansion chamber that allows the engine to breathe freely without the clogging burden of silencers. Bultaco says that this pipe brings engine output up to 30 bhp, compared to 22 bhp in street trim. On the drag strip, the use of this expansion chamber cut the Matador’s quarter-mile time to a best of 17.01 sec., which is as close to the 16-sec. bracket as makes no difference. Moreover, terminal speed rose from 66.2 mph, using the street setup, to 71.8 mph, with the enduro pipe. Drag strip performances normally offer little of interest to dirt riders, but in this case, the times and speeds form an indication of the Matador’s improved breathing qualities when the Stage III exhaust system is used.

Although the enduro pipe is an extra, at a price of $25, it forms the greatest bargain ever in bolt-on goodies, for it provides a claimed increase of 8 bhp over the street setup. Bultaco at first decided to offer a more extensive speed package, comprised of the head and other parts from the Pursang motocross racer, at a price of $150. Fortunately, the factory chiefs amended their decision, and incorporated the Pursang components as standard equipment on the Matador, and made only a minimal increase in the price of the machine. Thus, the customer gets these parts virtually free, and needs only the special pipe to enable the Pursang head to prove its value. And who else offers a gain of around 8 bhp for as little as $25? Moreover, the bike can be switched from the street to the “hot” exhaust setup in less than 10 min. Two nuts and bolts, two screws, a spring, a rubber band, and the exhaust pipe flange nut are the only parts that must be tampered with to make the change. Everything else remains the same—even the carburetor jets need not be altered.

While Bultaco still claims 22 bhp from the Matador’s improved engine, the 1969 version boasts much greater zest in the lower rpm range. The factory equips the bike with a 32-mm Spanish-built Amal concentric carburetor, in place of the previous 24-mm 1RZ unit, and this modification alone is said to provide much of the additional low-speed power. In fact, it’s almost impossible to believe that the bike is only a 250. Carburetion is remarkably clean at all engine speeds, and the bike surges doggedly onward at times when the rider expects it to choke and die.

The suspension has not been changed from the previous model, for one very good reason—the fork and rear swinging arm already perform faultlessly. The front end, in particular, is astounding in the way it floats over all kinds of barriers, gullies, and potholes without deflection or jarring. During a very rough session over treacherous terrain, the front fork could not be made to bottom. The rear suspension units, adjustable to five different positions, work equally well. The xMatador can be thrashed furiously over ruts, but the rear wheel refuses to wag far out of line.

The front brake on the test bike squealed loudly, but this was probably because the machine was almost brand new. Otherwise, both front and rear units provide quick stops, and, equally important, sufficient feel for the rider to squeeze hard, without locking the wheels.

A five-speed gearbox gives the Matador a ratio for any kind of situation in the dirt. First gear makes a stump-puller for starts and steep climbs. Otherwise, second manages the majority of low-speed going, aided by the clean carburetion and tremendous engine torque. The gear lever is mounted on the right, in English style, and the change pattern follows a one-down, four-up movement. The other controls are accurately placed. The clip-on handlebars follow motocross practice more than anything else, while the seat is a huge, well-padded layer of foam. Two slots, one on each side of the seat, allow air to reach the filtration system, which is mounted beneath the nose of the seat. The position of the slots, just behind the rider’s thighs, is claimed to be the driest part of a motorcycle.

The Matador boasts a long list of features that are really useful in the dirt. The 3.5-gal. fiberglass fuel tank ensures a long day’s riding without stops for fuel. Bultaco’s fully-enclosed rear chain system is now famous, while the cush drive rear hub provides smooth power transmission. Alloy wheel rims are fitted, yet the Matador is no lightweight. With a half-tank of fuel, it weighs 265 lb. The fact that it feels 50 lb. lighter is a tribute to the fine handling built into the bike.

The serious dirt rider could trim the figure considerably, however, by removing the lights, speedometer, passenger footpegs, and street mufflers. In this Spartan trim, the Matador handles and goes like a true motocross racer, and it will certainly hang right in there during any of those spontaneous races that arise when motorcyclists get together in the dirt. Afterward, the Matador man can bolt the parts back on, and ride home. Or, he can take his best buddy on a fishing trip into the mountains; or play at trials; or just cruise the hills all day. The Matador is that good; it could even be the most versatile off-roader ever built.

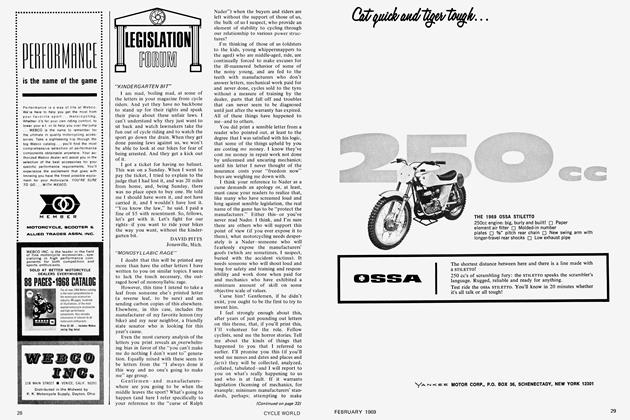

But what of Bultaco’s more specialized bike, the Sherpa T?

When SuperSam (Miller, that is) was on tour in the U.S., toward the end of 1968, he never missed an opportunity to criticize a trials machine. To some people this was passed off as prejudice. After all, isn’t Sammy the man responsible for development of the Bultaco Sherpa T? On questioning, the world’s greatest trials rider would not hesitate to confide that the fabulous Sherpa T, out of the box, requires considerable work to make it acceptable for serious trials. This always was followed by oohs, ahs and gasps from the inquisitive. As a factory rider, Sam is expected to say his company’s product is perfect and cannot be improved.

Then Sammy would explain he has a manufacturing company in England that makes all of the parts necessary to transform the standard Sherpa T into the best rock-basher’s mount in the world. Parts include a 7-lb. lighter frame; special fork top clamp, which permits a more secure handlebar mount; different footpegs; softer rear springs for the damper units; alloy gasoline tank, and various other refined bits for the truly mad trials exponent.

Sam is producing and selling these supergoodies, apparently with the sanction of the Bultaco factory. At least officials do not seem to mind what Sammy does on the side. During his trip, however, came news that Bultaco was developing a lighter version of the Sherpa T, a move conceived to incorporate the majority of the maestro’s ideas into the production models. When questioned on this aspect, Sam simply replied, “Guess I’ll have to go home and put on the thinking cap again, eh.” And at this point it was obvious that Miller was not completely in the dark as to what was happening in Barcelona. In fact, a good guess is that he knew many months before the tour exactly what changes would appear on the new machines.

It was, therefore, with considerable interest that CYCLE WORLD waited for the 1969 Sherpa T. Because a true trials mount can be as exciting, emotionally, as a grand prix road racer, or a mile track racer. The difference is that, as CW has pointed out before, a good trials motorcycle is an excellent trail tool, but not vice versa. With that thought in mind, even the most professional trials machine available is a pretty good trail bet, whether the owner’s bag is fishing in a remote area, or fun riding in impossible terrain.

The Sherpa T, because it is a trials mount of professional caliber, is not fitted with lighting equipment, or any of the other bits to make it legal for street use. There is a rubber license holder at the rear to permit the owner to tack on his registration while traveling on public roads between sections, but that is the extent of the street legal gear. The seat, for example, simply is something better than the rear fender when sitting. The pegs are too high when sitting on that article called a seat. If, however, the Sherpa T is taken to native haunts of mountain goats, or to some place where no other vehicles can pass, all of the things the rider does without are gladly forsaken; the lack of frills is a tribute.

Appearance of the 1969 five-speed Sherpa T has changed considerably over last year’s five-speed model. The previous seat was a very scantily-padded, small affair, but the latest one is even smaller, permitting it to be placed lower in the notch between the gas tank and rear mudguard. Seat height now is a minimal 29.6 in., and width has been reduced to 5.7 in. A much slimmer fuel tank shape, and a muffler which blends into the fiberglass side panel, allow the rider to keep his knees very close together, thus making it easier to use body lean in tough going.

One baffling thing is that, despite rumors that the factory has incorporated lighter equipment, the new Sherpa T is identical in weight to the 1967 version tested by CW. This is not to say the new model is heavy, simply that it is no lighter than the previous four-speed machine. A curb weight of 219 lb. makes it the lightest of full-sized 250 trials mounts.

Bultaco saved a little weight by adopting a slimmer rear damper unit, and rear wheel behavior has been improved by fitting softer springs. The addition of a spring loaded rear chain tensioner, however, has added fractional poundage. This probably is the first production trials machine to employ a rear chain tensioner, and its benefits are truly worthwhile. Not only is the chain less likely to become damaged in rockery, but power transmission is considerably more smooth.

There is some confusion in the horsepower claims, as well as weight figures. Last year, the Sherpa T featured a 24-mm IRZ carburetor, and was rated at 19.6 bhp. This year, with completely redesigned cylinder porting and a 27-mm Amal concentric, to improve power, the claim of 19.5 bhp seems out of place. Regardless of what has happened to peak horsepower, the engine definitely is stronger at the lower end of the scale. There is no doubt that the engine changes have resulted in a cohsiderable power increase in the 2000to 3000-rpm range. The front end now can be lofted over almost impossible obstacles without the need for vigorous throttle movement.

When a machine is as refined as the Sherpa T, the changes will be very subtle and, even with Sammy Miller’s energetic mind around, Bultaco must be hard put to give the customers something new each year. Apart from a narrower motorcycle, a chain tensioner and engine modifications, there are very minor detail alterations. The gas tank filler cap features a long, screw-on neck, and an O-ring for sealing. The tank is permitted to breathe through a tube which is routed down through the steering head. Thus, if the machine lands upside down, the tank will not spew its contents on the ground. The footpegs have been lowered to 13.5 in. to maintain a reasonable seat-to-peg relationship. Front fork stanchions now are knurled at the lower triple clamp to prevent the fork twisting problem frequently encountered on previous models.

Although the changes may seem minor, they represent, at least for the Sherpa T, what could be considered an almost completely new machine. The suggested retail price of $849 may be steep for a motorcycle with no lighting equipment and a hard seat, but the Sherpa T remains the most sought after trials mount in the world.

There they are,a pair of Sr. Bulto’s best. They’re the stuff of off-road riders’ dreams.

BULTACO MATADOR

SPECIFICATIONS

$859

PERFORMANCE