COPETOWN

COMPETITION

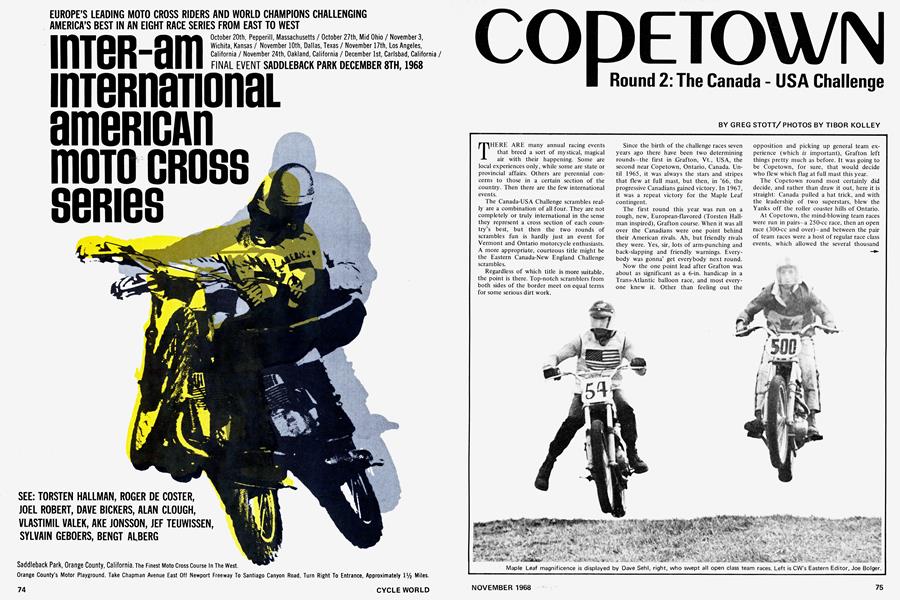

Round 2: The Canada - USA Challenge

TIBOR KOLLEY

THERE ARE many annual racing events that breed a sort of mystical, magical air with their happening. Some are local experiences only, while some are state or provincial affairs. Others are perennial concerns to those in a certain section of the country. Then there are the few international events.

The Canada-USA Challenge scrambles really are a combination of all four. They are not completely or truly international in the sense they represent a cross section of each country's best, but then the two rounds of scrambles fun is hardly just an event for Vermont and Ontario motorcycle enthusiasts. A more appropriate, courteous title might be the Eastern Canada-New England Challenge scrambles.

Regardless of which title is more suitable, the point is there. Top-notch scramblers from both sides of the border meet on equal terms for some serious dirt work.

Since the birth of the challenge races seven years ago there have been two determining rounds—the first in Grafton, Vt., USA, the second near Copetown, Ontario, Canada. Until 1965, it was always the stars and stripes that flew at full mast, but then, in '66, the progressive Canadians gained victory. In 1967, it was a repeat victory for the Maple Leaf contingent.

The first round this year was run on a rough, new, European-flavored (Torsten Hallman inspired), Grafton course. When it was all over the Canadians were one point behind their American rivals. Ah, but friendly rivals they were. Yes, sir, lots of arm-punching and back-slapping and friendly warnings. Everybody was gonna' get everybody next round.

Now the one point lead after Grafton was about as significant as a 6-in. handicap in a Trans-Atlantic balloon race, and most everyone knew it. Other than feeling out the opposition and picking up general team experience (which is important), Grafton left things pretty much as before. It was going to be Copetown, for sure, that would decide who flew which flag at full mast this year.

The Copetown round most certainly did decide, and rather than draw it out, here it is straight: Canada pulled a hat trick, and with the leadership of two superstars, blew the Yanks off the roller coaster hills of Ontario.

At Copetown, the mind-blowing team races were run in pairs-a 250-cc race, then an open race (300-cc and over)—and between the pair of team races were a host of regular race class events, which allowed the several thousand fans to catch their breath, and still see good racing. To be sure that the winning country was deserving, the four sponsoring Ontario clubs ran eight team races (four for each class). Incidentally, a team is comprised of four riders, but there usually is a substitute for each class hiding in the pits, trying to calm his rising ulcers.

The aforementioned two Canadian superstars who virtually dominated their classes were Seppo Makinen and Dave Sehl. Makinen is a native of Finland and one-time junior champion of that country. The blond Finn amazed everyone with the absolutely brilliant handling of his Bultaco. In the 250 class he won three of the four races and finished one, the third, with a flat rear tire. Chances are good he would have taken that one too.

Winning prowess in the open team events was demonstrated by 22-year-old Sehl. He won all the open team races on a gusty 500-cc Rickman Triumph Metisse, and held off the stiffest American competition, in particular veteran Glen Vincent and super veteran Joe Bolger.

As stated earlier, Makinen was the reckoning force in the 250 class, but one could have counted on powerful Yank opposition from New Hampshire's Bruce MaGuire, had the rotund No. 7 been able to ride. "Super Bruth," as he's fondly called, broke one of those oh-so-breakable collarbones at an Ontario scramble the previous day, and with it, snapped a little team confidence.

Bruce could have been counted on for 2nds and 3rds, but truly, it's rather unlikely he would have vanquished the remarkable Finn. Bruce goes mighty fast at times (and does it all sitting down too), but he tires toward the end of long races, and his lap times increase slightly-if he doesn't fall off first. Makinen's lap times always are fast and consistent, and rarely vary more than a second.

In the third race, when Makinen slowed with a flat rear tire (and for the first time most anyone could recall, fell off), things were left wide open for the great Yvon du Hamel. For the little tiger, just back from his Indianapolis misfortune, this was his first team race of the day. In past years the versatile Frenchman (remember Daytona) was one of the true Canadian superstars. In '65, '66, and '67 he won, in spectacular fashion, every open team event on the Copetown slopes.

For the first round this year there was no open class machine available from the distributor, so he became part of the 250 team strategy. At Copetown, however, the anxious CZ distributor turned up with a new 360 single-port. What to do? Switching Yvon to the open class would have meant weakening the 250 team. So, to make it legal for him to show off the 360 (in regular open expert races), and still ride as a 250 team member on the smaller CZ, he was pulled from the first two team races.

Because Bultaco always seems to follow Bultaco home, the like appears true of CZs. When Yvon's 250 finished 1st, Connecticut's Jim Weinert ran 2nd on another Czech bomb. The most useful 250 American team member was likely Bob Owens of Connecticut. Consistency is important in team racing, and that is how Bob could best be describedconsistent. He finished all four heats, which no other 250 Yank team member managed, in reasonable positions. In the last 250 team race Canadians finished 1-2-3-4, but young Bob pushed his colorful Bultaco from a bad-start last place, spurring his fellow members on all the way, to finish 5th and first American.

For Canada, Mo Fraser was the best supporting 250 rider, following Makinen home in three races, and earning a 3rd in du Hamel's event.

So, in the 250 races the Canadians had a reasonable time of it. With the exception of MaGuire who didn't ride, most of New England's team experience had moved to the open class. That means Joe Bolger, George Parmalee and Ron Jeckel are gone, leaving a difficult task for some apprehensive newcomers.

With so many riders changing to bigger iron, it was not surprising that competition stiffened in the open team races. Canadian Dave Sehl did run away, but despite the plain fact he's a two-wheel natural from a family of two-wheel naturals, his performances are... well, interesting. Other than Grafton, he had not scrambled before this year, though he dirt tracks successfully in the eastern states. Also, the lanky Sehl had been downed for a week with a severe virus immediately after Grafton (where he won three out of four races).

Joe Bolger, astride a 360 Bultaco, followed Dave home in the first race and the rest of the pack went Canuck, Yank, Canuck, Yank, to 8th place.

In the second open race Joe repeated his 2nd place, but behind him came the best open class Canadian back-up rider, Doug Sehl. That's right, the "kid brother" of Dave. The unlikely looking 18-year-old can really tear up the sod on his 360 Bultaco, and it was Doug, incidentally, whom World Champion Torsten Hallman had some kind words to say about on his visit to Canada in late 1966.

Every time Bolger and the "kid" dueled, which was frequent enough, Joe would get this wrinkle in his brow, and obviously was thinking, "Oh to have that kid's energy and my experience."

Both Joe and Doug were consistent, and that's very important Glen Vincent, brother of New England's renowned Charlie Vincent, and a rider in his own right, ran 2nd in the last two heats, but again the younger Sehl was there to shake things up. Vincent, incidentally, appeared to be a little off that day. He was a man of no nonsense, but the edges were rough.

Flying elbows, flailing legs and similar foul play can't come under discussion because there is nothing to talk about. There was about as much physical contact during the meeting as a chaperoned fraternity-sorority football match.

Clean riding always has been a natural attribute of the Challenge races. Certainly one might say that it's only because consistency is important in building up team points and no one wants to be black flagged, but primarily it's winning (or losing) fair and square that counts.

Corner blocking, which is decidedly clean, heightened spectator interest in a couple of the team races. In one open event an American tried a shade too hard to catch Sehl and went down. By the time it took him to arrange his limbs and shake some dust off, Sehl was coming around again. Bolger was on his tail, so what possible alternative could the first rider have but to get back on his machine pronto, and take things mighty slow through the next couple of off-camber bends. He did this in his attempt to slow Sehl for a gaining Bolger, but alas, Sehl, like the expert he is, slipped around and regained the lost yardage.

As far as the standard racing classes are concerned, they were naturally not as international, nor as electrifying, as the team races. Almost 100 riders, the majority regular Canadian sportsmen, picked away at each other during their 18 respective races and provided a show worthy of the admission price.

While they rounded out the day's events nicely, the final spectacle was the all comers Grand Prix. It was a race that allowed all caliber of riders to make their last attempt for a class position that might sound satisfactory at the supper table.

The Grand Prix started juniors first, seniors next, then the cool experts, three-quarters of a lap behind. Could they do their thing in 20 laps and overcome the handicap? Yes! At least Dave Sehl, Seppo Makinen and Yvon du Hamel did. When the experts were waved away, Sehl's Rickman Triumph just blew off the line in possibly his most excellent start that defeated his very close competitor, Makinen. At the end, Sehl was almost the same distance ahead of Makinen as he had been in the first few laps. It was a majestic finish to a grand prix day.

Smiling Yvon du Hamel finished in 3rd, and as he did an enthused television cameraman, obviously bilingual, shouted merrily, "C'était une affaire d'honneur." And the gentleman was right!

The American 250 team members were: Bruce MaGuire, Marlboro, N.H., (Bultaco); Jim Weinert, Middletown, N.Y., (CZ); Bob Owen, Southington, Conn., (Bultaco); Cliff Frazee, South Natick, Mass., (CZ); and Joe Higgins, Dorchester, Mass., (CZ).

The Canadian 250 team members were: Seppo Makinen, Toronto, Ont;., (Bultaco); Yvon du Hamel, Montreal, Que., (CZ); Maurice Fraser, Hamilton, Ont., (Bultaco); Jerry Vandereyken, Acton, Ont., (CZ); and Carl Bastedo, Niagara Falls, Ont., (Yamaha).

The American open team members were: Glen Vincent, Simsbury, Conn., (CZ); George Parmelee, Fairfield, Conn., (Montesa); Ron Jeckel, Glen Falls, N.Y., (Greeves); Mel Gáneos, Woodmont, Conn.; and Joe Bolger, Barre, Mass., (Bultaco).

The Canadian open team members were: Jack Hunt, Guelph, Ont., (CZ); Gunter Sauren, Downsview, Ont., (CZ); Norm Richens, Clarkson, Ont., (Greeves); Dave Sehl, Waterdown, Ont., (Triumph); and Doug Sehl, Waterdown, Ont., (Bultaco).