TRIUMPH DAYTONA RACER ★

THE TRIUMPH FACTORY stopped taking an active interest in racing almost 18 years ago when the Triumph Grand Prix project came to an end. But American tuners, being what they are, saw an engine that lent itself to home tuning; one that could be very competitiye under AMA rules. And through the years, the 500 Triumph can boast a staggering list of successes in this country. All of this has been done with American speed accessories, from special crankshafts to racing valve springs.

This changed somewhat when the Triumph factory obtained Doug Hele, a first class engineer who is more than a little interested in racing. One of Doug's first tasks was to develop a new fork for street Triumphs, an easy chore for someone who had worked on forks for the world's famous racing Nortons. To say the new front end helped the handling would be an understatement — it was a transformation. From that point on, the street Triumphs have become more sophisticated in almost every respect.

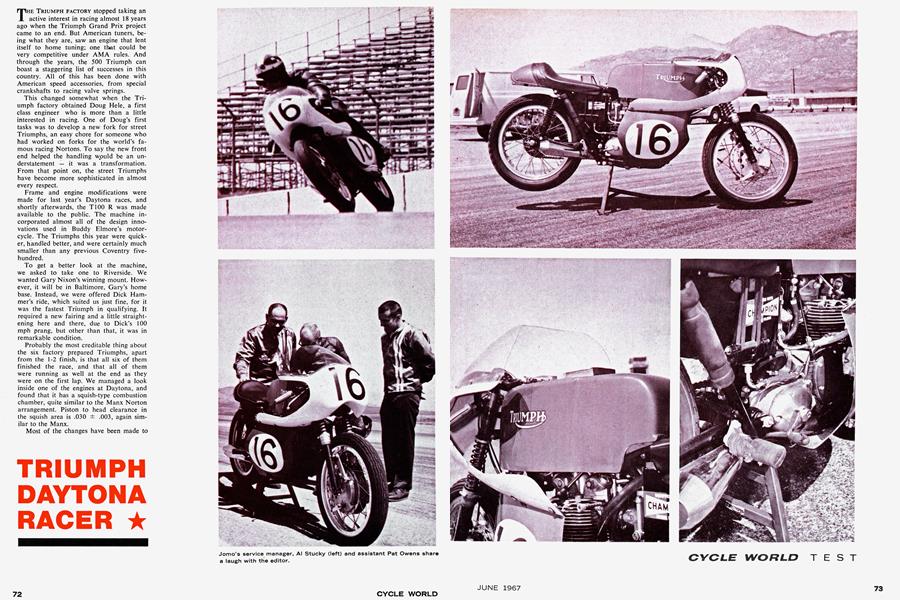

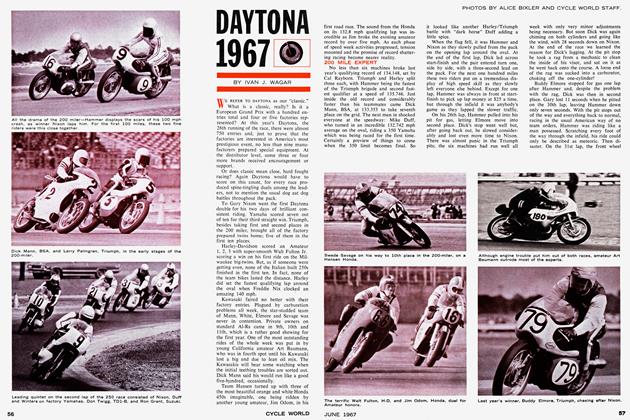

Frame and engine modifications were made for last year's Daytona races, and shortly afterwards, the T100 R was made available to the public. The machine incorporated almost all of the design innovations used in Buddy Elmore's motorcycle. The Triumphs this year were quicker, handled better, and were certainly much smaller than any previous Coventry fivehundred.

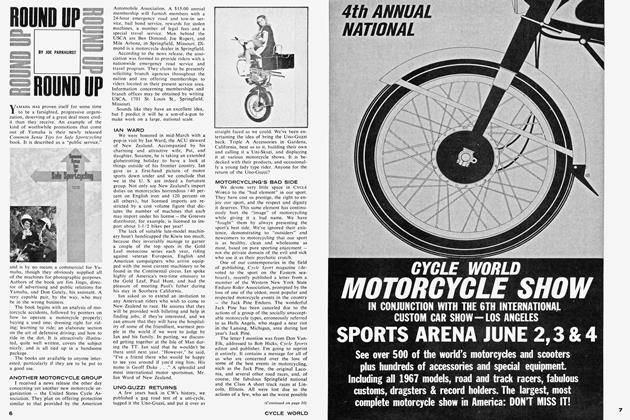

To get a better look at the machine, we asked to take one to Riverside. We wanted Gary Nixon's winning mount. However, it will be in Baltimore, Gary's home base. Instead, we were offered Dick Hammer's ride, which suited us just fine, for it was the fastest Triumph in qualifying. It required a new fairing and a little straightening here and there, due to Dick's 100 mph prang, but other than that, it was in remarkable condition.

Probably the most creditable thing about the six factory prepared Triumphs, apart from the 1-2 finish, is that all six of them finished the race, and that all of them were running as well at the end as they were on the first lap. We managed a look inside one of the engines at Daytona, and found that it has a squish-type combustion chamber, quite similar to the Manx Norton arrangement. Piston to head clearance in the squish area is .030 ± .003, again similar to the Manx.

Most of the changes have been made to

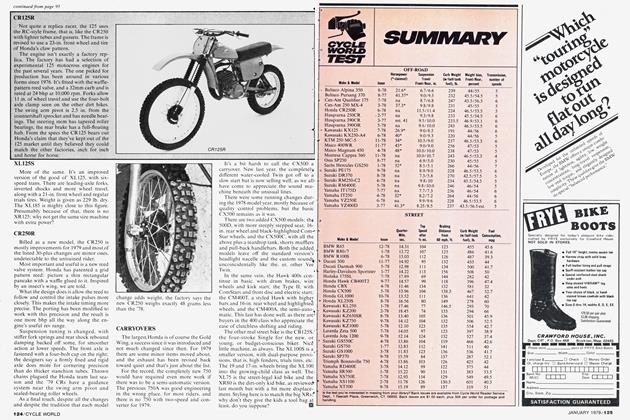

CYCLE WORLD TEST

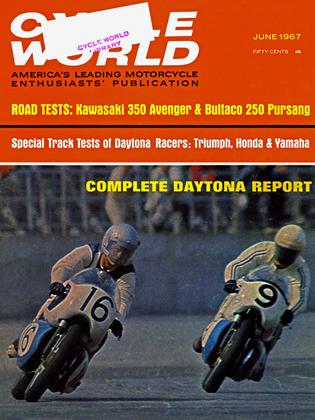

the cycle parts. Probably the largest single contributor to improved lap times was the new Fontana four leading shoe front brake. All of the riders liked it, once they had recovered from the shock of having the front wheel stop if the brake was used without discretion. In fact, it's the sort of brake that can be operated all the way with two fingers, or very gingerly with four. A standard Triumph rear brake is used on the back.

The Triumphs last year had very low frontal area, which sent everyone scurrying home to whittle their fairings. But this year, the machines were even smaller; in fact, as small as most of the 250 production racers in physical size. This was accomplished by fitting 18-inch wheels in place of the standard 19-inch that English racing machines have always used. Also, the front forks were shortened by cutting 1 inch from the top of the stanchions and sliding them up further into the fork crowns. A corresponding amount was removed from the fork springs to maintain the correct poundage.

Except for the kink in the right side member, to allow the exhaust pipe to pass inside, the frame has not been altered in any way. It is exactly the same frame used on the Daytona street model. Last year's ugly gas tank and seat have been replaced by very appealing units from Birmingham Fiberglass Mouldings. Now the rider can get down much lower, with considerably more comfort. The fairing is also much smaller than before, and all of the fiberglass components are surprisingly lightweight. The whole machine only weighs 301 pounds with a half tank of gas.

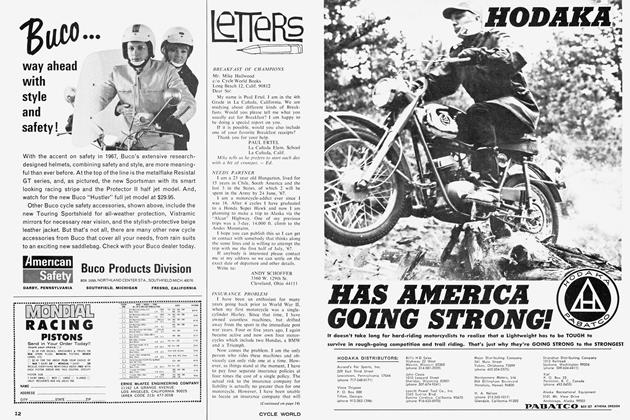

Externally, the engine does not appear to have changed greatly. The large radially finned exhaust pipe clamps have been replaced by plain, unfinned bands, to improve the airflow to the heads. All of the rear exhaust pipe mounts have rubber bushes, and are actually quite flexible. The carburetor arrangement is quite unusual, although it has been used on some of the European multis. An Amal flat-type float chamber is mounted between the two 1-3/16 Amal GPs. However, it is not hung on an adjustable rod; instead, the banjo outlet spigots are set at 180° and hook up rigidly to the carburetor inlet fitting. This means that the float chamber is fixed relative to the carburetors, and everything must be right in the beginning, as they cannot be adjusted. The advantage is that they cannot come unadjusted, either!

To prevent fuel frothing and all of the evils connected with rigid float chambers, the hoses between the carburetors and cylinderhead spigots are quite flexible. Two U-shaped brackets on the main frame downtube support the carburetor bells on rubber pads.

The oil lines have now been routed over the top of the gearbox, rather than underneath, to permit the right side exhaust pipe to tuck in close to the engine unit. More and more machines racing in the AMA are incorporating oil radiators. The main reason is that, under AMA rules, basic engine castings must be used. And, although cylinder and head finning may be ample for any touring requirements, it may be a marginal situation under prolonged hard racing. If the oil temperature can be kept down, it will act as a coolant and carry heat away. Daytona Triumphs, like last year, are fitted with a Chevrolet Corvair oil cooler.

Even from cold, the Triumph started well, although the oil cooler did prolong the warmup time considerably. First gear is slightly higher than second on the street counterpart, and it might be expected, with a highly tuned racing engine, to require considerable clutch slip to get underway. However, an extremely wide power band makes the task an easy one. In fact, as we see it, the really good torque characteristics of the engine contributed much to the machine's phenomenal success at Daytona. The machine can be ridden at anything over 4,500 rpm, and from 6,000 rpm to red line, things happen very quickly, particularly in first and second gears. A good habit, when racing Triumphs, is to shift from first at least 500 revs below red line, because once the engine gets near peak in first, it can climb the last 500 revs in one second, near enough.

With Daytona gearing, Riverside Raceway becomes a very small course, indeed. Turn nine to turn one is virtually an Sbend. The rear springs were set up too far, initially, causing chop over the bumps at turn one; but setting them to the softest position sorted the handling out very well.

It can be said without reservation that the new Triumph is on par or better than anything else for handling, and that includes Manxes, G50s, 7Rs, Honda 4, last year's Triumph racer and various other racing equipment ridden at Riverside.

What a great production racer it would make! ■