ZUNDAPP ISDT REPLICA 125

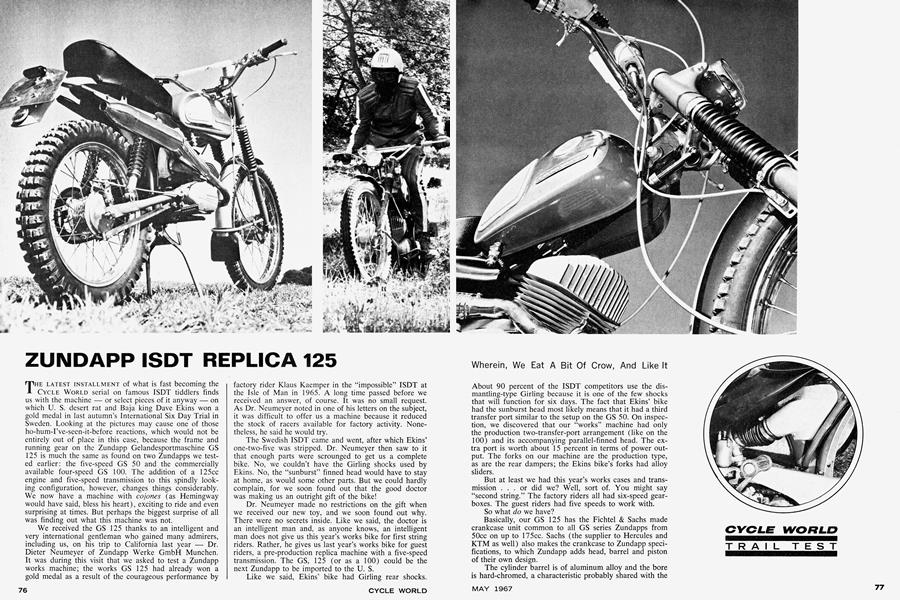

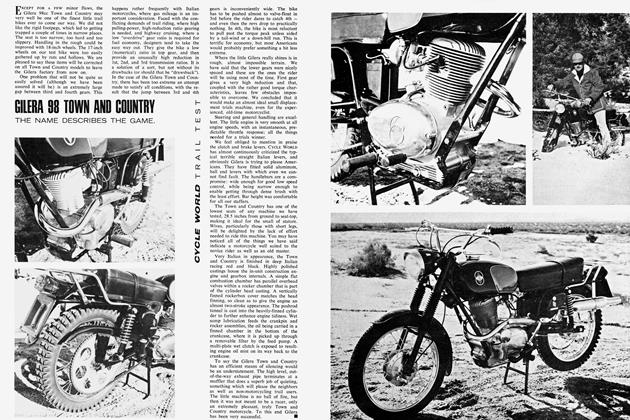

THE LATEST INSTALLMENT of what is fast becoming the CYCLE WORLD serial on famous ISDT tiddlers finds us with the machine — or select pieces of it anyway — on which U. S. desert rat and Baja king Dave Ekins won a gold medal in last autumn's International Six Day Trial in Sweden. Looking at the pictures may cause one of those ho-hum-I've-seen-it-before reactions, which would not be entirely out of place in this case, because the frame and running gear on the Zundapp Gelandesportmaschine GS 125 is much the same as found on two Zundapps we tested earlier: the five-speed GS 50 and the commercially available four-speed GS 100. The addition of a 125cc engine and five-speed transmission to this spindly look ing configuration, however, changes things considerably. We now have a machine with cojones (as Hemingway would have said, bless his heart), exciting to ride and even surprising at times. But perhaps the biggest surprise of all was finding out what this machine was not.

We received the GS 125 thanks to an intelligent and very international gentleman who gained many admirers, including us, on his trip to California last year — Dr. Dieter Neumeyer of Zundapp Werke GmbH München. It was during this visit that we asked to test a Zundapp works machine; the works GS 125 had already won a gold medal as a result of the courageous performance by

factory rider Klaus Kaemper in the "impossible" ISDT at the Isle of Man in 1965. A long time passed before we received an answer, of course. It was no small request. As Dr. Neumeyer noted in one of his letters on the subject, it was difficult to offer us a machine because it reduced the stock of racers available for factory activity. Nonetheless, he said he would try.

The Swedish ISDT came and went, after which Ekins' one-two-five was stripped. Dr. Neumeyer then saw to it that enough parts were scrounged to get us a complete bike. No, we couldn't have the Girling shocks used by Ekins. No, the "sunburst" finned head would have to stay at home, as would some other parts. But we could hardly complain, for we soon found out that the good doctor was making us an outright gift of the bike!

Dr. Neumeyer made no restrictions on the gift when we received our new toy, and we soon found out why. There were no secrets inside. Like we said, the doctor is an intelligent man and, as anyone knows, an intelligent man does not give us this year's works bike for first string riders. Rather, he gives us last year's works bike for guest riders, a pre-production replica machine with a five-speed transmission. The GS, 125 (or as a 100) could be the next Zundapp to be imported to the U. S.

Like we said, Ekins' bike had Girling rear shocks.

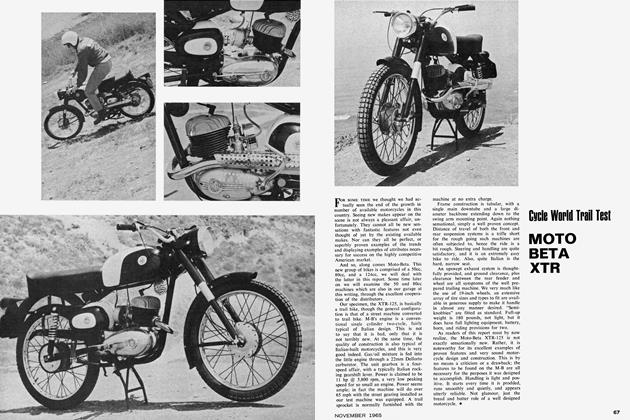

CYCLE WORLD TRAIL TEST

Wherein, We Eat A Bit Of Crow, And Like It

About 90 percent of the ISDT competitors use the dismantling-type Girling because it is one of the few shocks that will function for six days. The fact that Ekins' bike had the sunburst head most likely means that it had a third transfer port similar to the setup on the GS 50. On inspection, we discovered that our "works" machine had only the production two-transfer-port arrangement (like on the 100) and its accompanying parallel-finned head. The extra port is worth about 15 percent in terms of power output. The forks on our machine are the production type, as are the rear dampers; the Ekins bike's forks had alloy sliders.

But at least we had this year's works cases and transmission ... or did we? Well, sort of. You might say "second string." The factory riders all had six-speed gearboxes. The guest riders had five speeds to work with.

So what do we have?

Basically, our GS 125 has the Fichtel & Sachs made crankcase unit common to all GS series Zundapps from 50cc on up to 175cc. Sachs (the supplier to Hercules and KTM as well) also makes the crankcase to Zundapp specifications, to which Zundapp adds head, barrel and piston of their own design.

The cylinder barrel is of aluminum alloy and the bore is hard-chromed, a characteristic probably shared with the

real works machines. Likewise, the big and small ends of the connecting rod run on needle bearings. The flat top piston carries two rings in a conventional arrangement — a Dykes L-pattern ring to provide precise port timing and a compression ring farther down the skirt. The head is also of conventional, hemispherical design (concave curve on the outside, convex toward the middle). The flywheels and the connecting rod are highly polished, in works fashion.

As for the chassis, it is similar to the real works stuff, except for the aforementioned suspension changes. Design is excellent and strong, with main tube and outrigger swing arm worthy of a much larger displacement machine. The 52.5-inch wheelbase offers a steady going over the roughest surfaces. The telescopic forks have an amazing six-plus inches of travel, while the rear spring/damper units offer about four inches, which is equally as generous. The ride is extremely soft and one can go for hours nonstop without fatigue.

Ground clearance is excellent. We measured it from the lowest point amidships, as is our usual practice, and came up with 10 inches. However, this low point is so close to the rear wheel that it would be well to mention that points farther forward are more than a foot from the ground. As is the case with all machines designed strictly for multi-day trials, the placement of center of gravity suffers a bit in the attempt to get maximum ground clearance. Hence, the Z,undapp's tendency to sway slightly when underway. This is more than made up for by the fact that the machine is virtually unstoppable in morasses that would sink a motocross machine.

Combined with the bike's super-light 191-pound weight (50 pounds lighter than some of its competitors in the same or smaller classes), the high center of gravity con-

spires to produce a thrilling phenomenon for the unsuspecting rider who thinks that the comfortable seat is for sitting upon all the time — it wheelies oh so readily in the lower gears, going uphill or around curves, Arbekov-style. Gold medalist Ekins rightfully comments that the bike is designed to be ridden in a standing position and that this is the position most ISDT riders assume during the entire six days. The logic is that, relatively speaking, the center of gravity is lower when one is standing up, in which position the swaying we mentioned does not exist. Additionally, the front end can be held down if the rider stands, which is made quite easy by the Zundapp's excellent control and foot peg layout.

Having five gears coupled to an engine with a broad torque range means that fifth will give speeds worthy of a freeway, while first will be unstoppable to the point of breaking loose before it bogs down. Thus, the GS 125 tops 60 mph easily, while still being able to chew its way up steep, tacky slopes. The spacing seems just right; the only reason a factory rider might want a sixth gear is to pull a higher top gear.

In sum, we wait with our fingers crossed to see if Dr. Neumeyer and Zundapp will see fit to put this machine into production on a large enough scale to allow it to be priced within reach of the average dirt-riding enthusiast. The GS 100 was a fine but expensive machine because it was produced in small quantities. Due to our comments on the GS 100, it could soon be put into large-scale production and sold at a much lower price than previously.

We hope Zundapp will take us to heart on the GS 125 as well. It is a machine of high performance, yet reliable, and it is delivered in one of the best handling packages that money can buy.

ZUNDAPP

GS 125