Motorcycling Behind The Iron Curtain

CARLO PERELLI

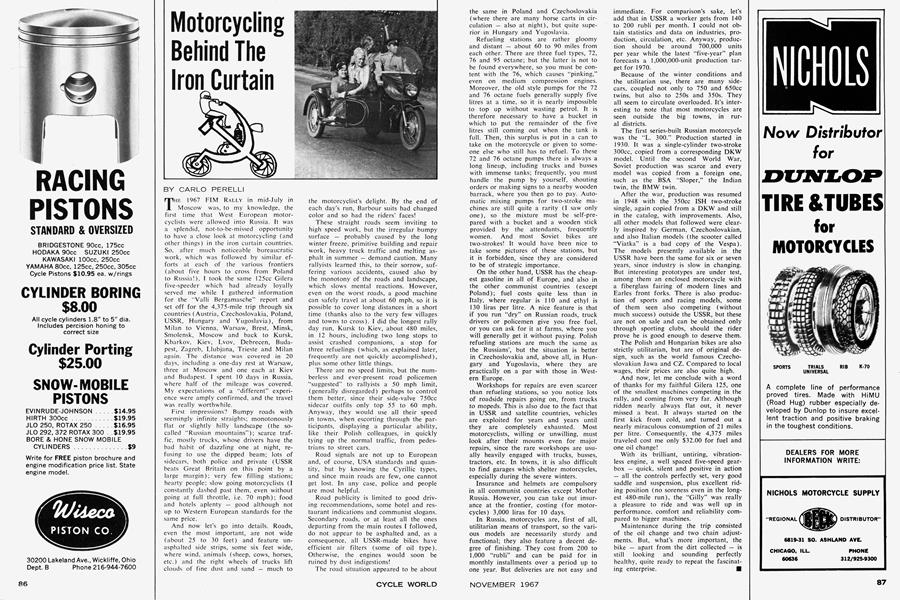

THE 1967 FIM RALLY in mid-July in Moscow was, to my knowledge, the first time that West European motorcyclists were allowed into Russia. It was a splendid, not-to-be-missed opportunity to have a close look at motorcycling (and other things) in the iron curtain countries. So, after much noticeable bureaucratic work, which was followed by similar efforts at each of the various frontiers (about five hours to cross from Poland to Russia!), I took the same 125cc Gilera five-speeder which had already loyally served me while I gathered information for the "Valli Bergamasche" report and set off for the 4,375-mile trip through six countries (Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, USSR, Hungary and Yugoslavia), from Milan to Vienna, Warsaw, Brest, Minsk, Smolensk, Moscow and back to Kursk, Kharkov, Kiev, Lvov, Debrecen, Buda pest, Zagreb, Llubjana, Trieste and Milan again. The distance was covered in 20 days, including a one-day rest at Warsaw, three at Moscow and one each at Kiev and Budapest. I spent 10 days in Russia, where half of the mileage was covered. My expectations of a "different" experi ence were amply confirmed, and the travel was really worthwhile.

First impressions? Bumpy roads with seemingly infinite straights; monotonously flat or slightly hilly landscape (the socalled "Russian mountains"); scarce traf fic, mostly trucks, whose drivers have the bad habit of dazzling one at night, re fusing to use the dipped beam; lots of sidecars, both police and private (USSR beats Great Britain on this point by a large margin); very few filling stations; hearty people; slow going motorcyclists (I constantly dashed past them, even without going at full throttle, i.e. 70 mph); food and hotels aplenty - good although not up to Western European standards for the same price.

And now let's go into details. Roads, even the most important, are not wide (about 25 to 30 feet) and feature unasphalted side strips, some six feet wide, where wind, animals (sheep, cows, horses, etc.) and the right wheels of trucks lift clouds of fine dust and sand — much to

the motorcyclist's delight. By the end of each day's run, Barbour suits had changed color and so had the riders' faces!

These straight roads seem inviting to high speed work, but the irregular bumpy surface — probably caused by the long winter freeze, primitive building and repair work, heavy truck traffic and melting asphalt in summer — demand caution. Many rallyists learned this, to their sorrow, suffering various accidents, caused also by the monotony of the roads and landscape, which slows mental reactions. However, even on the worst roads, a good machine can safely travel at about 60 mph, so it is possible to cover long distances in a short time (thanks also to the very few villages and towns to cross). I did the longest rally day run, Kursk to Kiev, about 480 miles, in 12 hours, including two long stops to assist crashed companions, a stop for three refuelings (which, as explained later, frequently are not quickly accomplished), plus some other little things.

There are no speed limits, but the numberless and ever-present road policemen "suggested" to rallyists a 50 mph limit, (generally disregarded) perhaps to control them better, since their side-valve 750cc sidecar outfits only top 55 to 60 mph. Anyway, they would use all their speed in towns, when escorting through the participants, displaying a particular ability, like their Polish colleagues, in quickly tying up the normal traffic, from pedestrians to street cars.

Road signals are not up to European and, of course, USA standards and quantity, but by knowing the Cyrillic types, and since main roads are few, one cannot get lost. In any case, police and people are most helpful.

Road publicity is limited to good driving recommendations, some hotel and restaurant indications and communist slogans. Secondary roads, or at least all the ones departing from the main routes I followed, do not appear to be asphalted and, as a consequence, all USSR-made bikes have efficient air filters (some of oil type). Otherwise, the engines would soon be ruined by dust indigestions!

The road situation appeared to be about the same in Poland and Czechoslovakia (where there are many horse carts in circulation — also at night), but quite superior in Hungary and Yugoslavia.

Refueling stations are rather gloomy and distant — about 60 to 90 miles from each other. There are three fuel types, 72, 76 and 95 octane; but the latter is not to be found everywhere, so you must be content with the 76, which causes "pinking," even on medium compression engines. Moreover, the old style pumps for the 72 and 76 octane fuels generally supply five litres at a time, so it is nearly impossible to top up without wasting petrol. It is therefore necessary to have a bucket in which to put the remainder of the five litres still coming out when the tank is full. Then, this surplus is put in a can to take on the motorcycle or given to someone else who still has to refuel. To these 72 and 76 octane pumps there is always a long lineup, including trucks and busses with immense tanks; frequently, you must handle the pump by yourself, shouting orders or making signs to a nearby wooden barrack, where you then go to pay. Automatic mixing pumps for two-stroke machines are still quite a rarity (I saw only one), so the mixture must be self-prepared with a bucket and a wooden stick provided by the attendants, frequently women. And most Soviet bikes are two-strokes! It would have been nice to take some pictures of these stations, but it is forbidden, since they are considered to be of strategic importance.

On the other hand, USSR has the cheapest gasoline in all of Europe, and also in the other communist countries (except Poland); fuel costs quite less than in Italy, where regular is 110 and ethyl is 130 liras per litre. A nice feature is that if you run "dry" on Russian roads, truck drivers or policemen give you free fuel, or you can ask for it at farms, where you will generally get it without paying. Polish refueling stations are much the same as the Russians', but the situation is better in Czechoslovakia and, above all, in Hungary and Yugoslavia, where they are practically on a par with those in Western Europe.

Workshops for repairs are even scarcer than refueling stations, so you notice lots of roadside repairs going on, from trucks to mopeds. This is also due to the fact that in USSR and satellite countries, vehicles are exploited for years and years until they are completely exhausted. Most motorcyclists, willing or unwilling, must look after their mounts even for major repairs, since the rare workshops are usually heavily engaged with trucks, busses, tractors, etc. In towns, it is also difficult to find garages which shelter motorcycles, especially during the severe winters.

Insurance and helmets are compulsory in all communist countries except Mother Russia. However, you can take out insurance at the frontier, costing (for motorcycles) 3,000 liras for 10 days.

In Russia, motorcycles are, first of all, utilitarian means of transport, so the various models are necessarily sturdy and functional; they also feature a decent degree of finishing. They cost from 200 to 1,000 "rubli" and can be paid for in monthly installments over a period up to one year. But deliveries are not easy and

immediate. For comparison's sake, let's add that in USSR a worker gets from 140 to 200 rubli per month. I could not obtain statistics and data on industries, production, circulation, etc. Anyway, production should be around 700,000 units per year while the latest "five-year" plan forecasts a 1,000,000-unit production target for 1970.

Because of the winter conditions and the utilitarian use, there are many sidecars, coupled not only to 750 and 650cc twins, but also to 250s and 350s. They all seem to circulate overloaded. It's interesting to note that most motorcycles are seen outside the big towns, in rural districts.

The first series-built Russian motorcycle was the "L. 300." Production started in 1930. It was a single-cylinder two-stroke 300cc, copied from a corresponding DKW model. Until the second World War, Soviet production was scarce and every model was copied from a foreign one, such as the BSA "Sloper," the Indian twin, the BMW twin.

After the war, production was resumed in 1948 with the 350cc ISH two-stroke single, again copied from a DKW and still in the catalog, with improvements. Also, all other models that followed were clearly inspired by German, Czechoslovakian, and also Italian models (the scooter called "Viatka" is a bad copy of the Vespa). The models presently available in the USSR have been the same for six or seven years, since industry is slow in changing. But interesting prototypes are under test, among them an enclosed motorcycle with a fiberglass fairing of modern lines and Earles front forks. There is also production of sports and racing models, some of them seen also competing (without much success) outside the USSR, but these are not on sale and can be obtained only through sporting clubs, should the rider prove he is good enough to deserve them.

The Polish and Hungarian bikes are also strictly utilitarian, but are of original design, such as the world famous Czechoslovakian Jawa and CZ. Compared to local wages, their prices are also quite high.

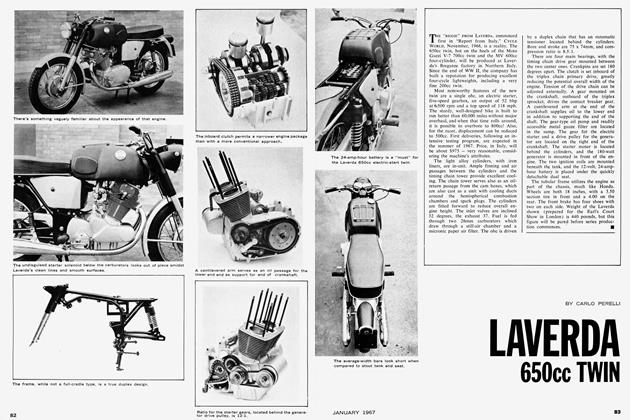

And now, let me conclude with a word of thanks for my faithful Gilera 125, one of the smallest machines competing in the rally, and coming from very far. Although ridden nearly always flat out, it never missed a beat. It always started on the first kick from cold, and turned out a nearly miraculous consumption of 21 miles per litre. Consequently, the 4,375 miles traveled cost me only $32.00 for fuel and one oil change!

With its brilliant, untiring, vibrationless engine, a well spaced five-speed gearbox — quick, silent and positive in action — all the controls perfectly set, very good saddle and suspension, plus excellent riding position (no soreness even in the longest 480-mile run), the "Gilly" was really a pleasure to ride and was well up in performance, comfort and reliability compared to bigger machines.

Maintenance during the trip consisted of the oil change and two chain adjustments. But, what's more important, the bike — apart from the dirt collected — is still looking and sounding perfectly healthy, quite ready to repeat the fascinating enterprise. ■