THE SCENE

IVAN J. WAGAR

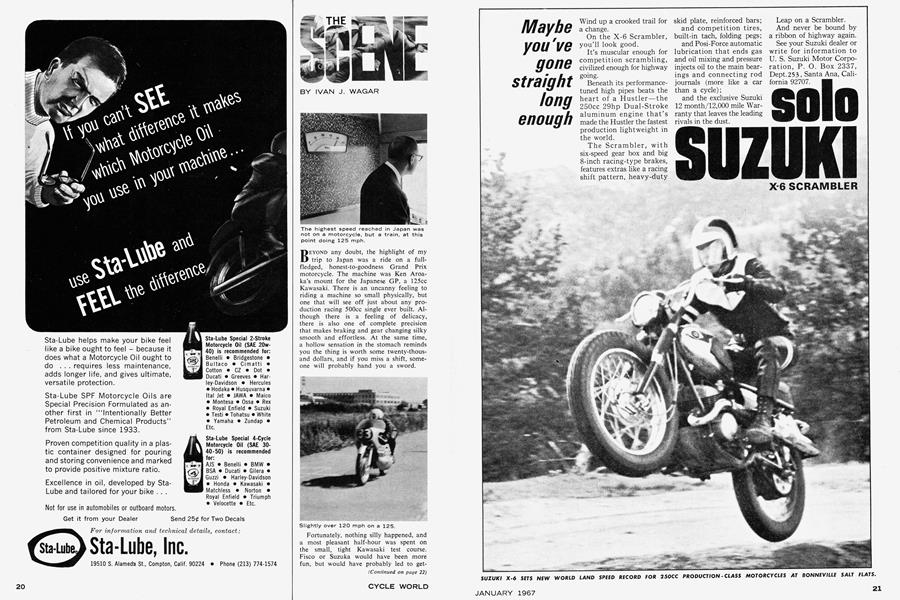

BEYOND any doubt, the highlight of my trip to Japan was a ride on a fullfledged, honest-to-goodness Grand Prix motorcycle. The machine was Ken Aroaka's mount for the Japanese GP, a 125cc Kawasaki. There is an uncanny feeling to riding a machine so small physically, but one that will see off just about any production racing 500cc single ever built. Although there is a feeling of delicacy, there is also one of complete precision that makes braking and gear changing silky smooth and effortless. At the same time, a hollow sensation in the stomach reminds you the thing is worth some twenty-thousand dollars, and if you miss a shift, someone will probably hand you a sword.

Fortunately, nothing silly happened, and a most pleasant half-hour was spent on the small, tight Kawasaki test course. Fisco or Suzuka would have been more fun, but would have probably led to getting carried away, literally.

(Continued on page 22)

In the tradition of any fine, well-prepared race machine, speed is deceptive. It is quite easy to arrive somewhere traveling faster than originally intended. However, the pipes and fairing are high, and with nothing to drag on the deck, it is comparatively easy to scrape through situations that would be impossible on a heavier race machine.

Engine specifications are not a big secret, as the factory has almost completed development on next year's four-cylinder model. The machine I rode has served its purpose in giving Kawasaki an inside first-hand look at GP racing. The factory wisely chose an orthodox engine design to explore racing, rather than start out with some exotic fantasy that might lead to years of headaches, without yielding realistic information in return. So, although the motorcycle is only a little over one year old, it is, for all intents and purposes, now obsolete.

With a total weight of 192 pounds, a power output of 32 bhp at 14,000 rpm and an eight speed transmission, it is not difficult to understand why performance is so brisk. In addition to a light oil mixture in the tank, the 125 also has a positive oil pump to the crankshaft components. It is interesting to note that some lapanese engineers feel that positive crankshaft lubrication is not necessary in racing two-stroke machinery, and may disappear on at least one famous racing machine next year.

I also had a ride on the Samurai pro duction racer which Kanaya used at Fisco, finishing second to Gary Nixon. Kanaya and Gary share the lap record, which is some six seconds faster than the old one for their class. These machines will be sold in this country and a shipment is planned to arrive for Daytona. Power, handling and brakes are excellent, and it will certainly be a force to be reckoned with in AMA races during 1967. This is the first time anyone from the press has been permitted to ride either of these rac ing machines and I am honored that Ka wasaki had sufficient faith in me, espe cially with the one-two-five.

(Continued on page 24)

A T Honda R&D, I saw a new material, which is called "Honda Metal." Very similar in appearance and weight to alumi num, it is almost as strong as steel. The main advantage is that the metal may be machined, very nearly, in the same way as aluminum, and, therefore, there is a con siderable saving in machine shop time, not to mention the life of tools used to machine the parts after casting. In fact, the metal is slightly more costly to pro duce than steel, but parts can be cast very accurately with minimal machining to achieve a finished component.

One of the prime uses of Honda Metal at this time, is the one-piece camshaft and drive sprocket for the Little Honda, the 50cc moped with the engine as an integral part of the rear wheel. The camshaft has the same dimensions as if it were made from steel, that is, the part has not been scaled up in order to use a weaker metal, and the as-cast appearance looks almost like a finished part. No additional heat treating or conditioning is required to wear surfaces after machining. Although steel parts (chains, etc.) are running against the metal, they found during the longevity test that the wear qualities equaled steel.

With 800 engineers in the Research and Development section (180 have engineering degrees) and an energetic Sochiro Honda at the helm, it is not surprising to learn they have plans for even more exotic materials in the very near future.

(Continued on page 26)

B RIDGESTONE probably has the best hid den test track in all of Japan. But the trip was worth it, for I rode the 50 and 90cc junior machines that won at Fisco. To qualify for junior racing, the machines must be derived from standard production street motorcycles. It is, however, legal to fiddle with the ports and rotary valves, and to fit expansion chambers. Fifty cubic centimeter machines have never done much for me until this one. It is really remarkable just how fast it will go, even with the standard four-speed transmission.

After riding the fifty for awhile, the 90cc version was a bomb, and I was amazed to find it would do almost 100 mph. In fact, it lapped Fisco at 90 mph average!

A pleasant surprise was meeting an old acquaintance from the Isle of Man in 1963. At that time, Yoshitaka Iida was Honda's racing chief. Now he is manager of the gigantic Suzuka Circuit operation. Besides being one of the most amiable people I've ever met, I found him to be a fearless navigator when he accompanied me for some hot laps in a Honda sports car, and he told me where not to shut off.

ONE of the best news items of the year is that Fritz Scheidegger has now been declared the winner of the 1966 Isle of Man Sidecar TT. It will be remembered that Fritz finished the race 0.4 seconds ahead of Max Deubel, but because he did not use the fuel supplied, and, instead, went to a service station to fill up, the organizers disqualified him. But, and here's the rub — they waited until after the race to do it. The reason was that the fuel was not approved.

(Continued on page 28)

Now, after a full RAC hearing, it has been declared that Fritz is the winner, that, in fact, he did not gain any advantage by using the fuel he did, and if anything, the fuel might have, been a few octane less than that supplied. With the TT, Fritz has won all of the 1966 sidecar classics and is a true champion. To Fritz it means a good deal more, for the German newspapers had carried stories to the effect that he used an illegal fuel, and the garage business, that he went sidecar racing to build up, had started to fall off. Fritz now intends to quit racing and concentrate on his garage.