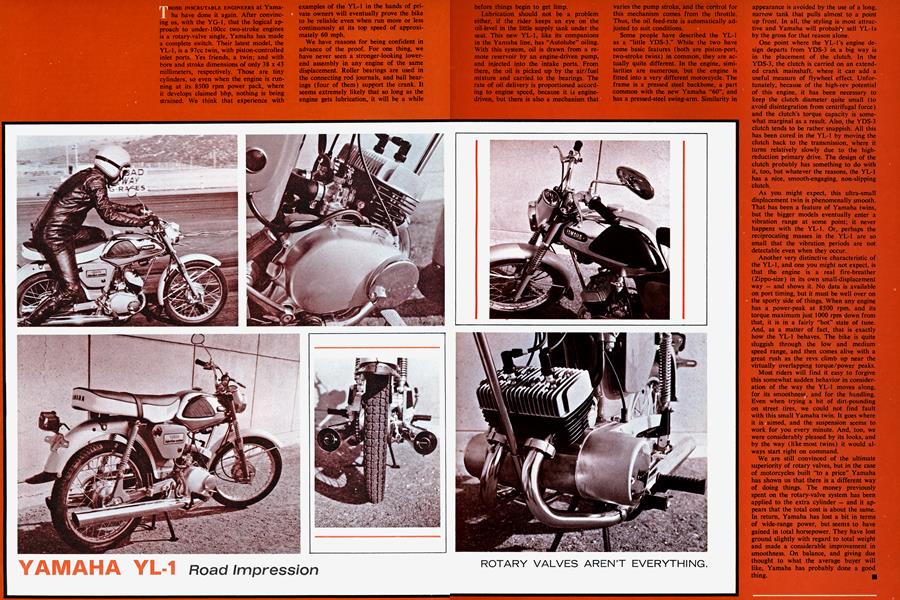

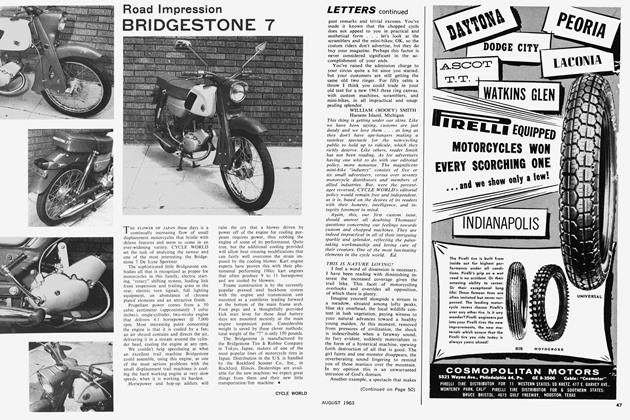

YAMAHA YL-1

Road Impression

THOSE INSCRUTABLE ENGINEERS at Yamaha have done it again. After convincing us, with the YG-1, that the logical approach to under-100cc two-stroke engines is a rotary-valve single, Yamaha has made a complete switch. Their latest model, the YL-1, is a 97cc twin, with piston-controlled inlet ports. Yes friends, a twin; and with bore and stroke dimensions of only 38 x 43 millimeters, respectively. Those are tiny cytinde, so even when the engine is running at its 8500 rpm power pack, where it develops claimed bhp, is strained. We think that experience with examples of the YL-1 in the hands of private owners will eventually prove the bike to be reliable even when run more or less continuously at its top speed of approximately 60 mph.

We have reasons for being confident in advance of the proof. For one thing, we have never seen a stronger-looking lowerend assembly in any engine of the same displacement. Roller bearings are used in the connecting rod journals, and ball bearings (four of them) support the crank. It seems extremely likely that so long as the engine gets lubrication, it will be a while before things begin to get limp.

Lubrication should not be a problem either, if the rider keeps an eye on" the oil-level in the little supply tank under the seat. This new YL-1, like its companions in the Yamaha line, has “Autolube” oiling. With this system, oil is drawn from a remote reservoir by an engine-driven pump, and injected into the intake ports. From there, the oil is picked up by the air/fuel mixture and carried to the bearings. The rate of oil delivery is proportioned according to engine speed, because it is enginedriven, but there is also a mechanism that varies the pump stroke, and the control for this mechanism comes from the throttle. Thus, the oil feed-rate is automatically adjusted to suit conditions.

Some people have described the YL-1 as a “little YDS-3.” While the two have some basic features (both are piston-port, two-stroke twins) in common, they are actually quite different. In the engine, similarities are numerous, but the engine is fitted into a very different motorcycle. The frame is a pressed steel backbone, a part common with the new Yamaha “60”, and has a pressed-steel swing-arm. Similarity in appearance is avoided by the use of a long, narrow tank that pulls almost to a point up front. In all, the styling is most attractive and Yamaha will probably sell YL-ls by the gross for that reason alone.

One point where the YL-l’s engine design departs from YDS-3 in a big way is in the placement of the clutch. In the YDS-3, the clutch is carried on an extended crank mainshaft, where it can add a useful measure of flywheel effect. Unfortunately, because of the high-rev potential of this engine, it has been necessary to keep the clutch diameter quite small (to avoid disintegration from centrifugal force) and the clutch’s torque capacity is somewhat marginal as a result. Also, the YDS-3 clutch tends to be rather snappish. All this has been cured in the YL-1 by moving the clutch back to the transmission, where it turns relatively slowly due to the highreduction primary drive. The design of the clutch probably has something to do with it, too, but whatever the reasons, the YL-1 has a nice, smooth-engaging, non-slipping clutch.

As you might expect, this ultra-small displacement twin is phenomenally smooth. That has been a feature of Yamaha twins, but the bigger models eventually enter a vibration range at some point; it never happens with the YL-1. Or, perhaps the reciprocating masses in the YL-1 are so small that the vibration periods are not detectable even when they occur.

Another very distinctive characteristic of the YL-1, and one you might not expect, is that the engine is a real fire-breather (Zippo-size) in its own small-displacement way — and shows it. No data is available on port timing, but it must be well over on the sporty side of things. When any engine has a power-peak at 8500 rpm, and its torque maximum just 1000 rpm down from that, it is in a fairly “hot” state of tune. And, as a matter of fact, that is exactly how the YL-1 behaves. The bike is quite sluggish through the low and medium speed range, and then comes alive with a great rush as the revs climb up near the virtually overlapping torque/power peaks.

Most riders will find it easy to forgive this somewhat sudden behavior in consideration of the way the YL-1 moves along, for its smoothness, and for the handling. Even when trying a bit of dirt-pounding on street tires, we could not find fault with this small Yamaha twin. It goes where it is aimed, and the suspension seems to work for you every minute. And, too, we were considerably pleased by its looks, and by the way (like most twins) it would always start right on command.

We are still convinced of the ultimate superiority of rotary valves, but in the case of motorcycles built “to a price” Yamaha has shown us that there is a different way of doing things. The money previously spent on the rotary-valve system has been applied to the extra cylinder — and it appears that the total cost is about the same. In return, Yamaha has lost a bit in terms of wide-range power, but seems to have gained in total horsepower. They have lost ground slightly with regard to total weight and made a considerable improvement in smoothness. On balance, and giving due thought to what the average buyer will like, Yamaha has probably done a good thing. g