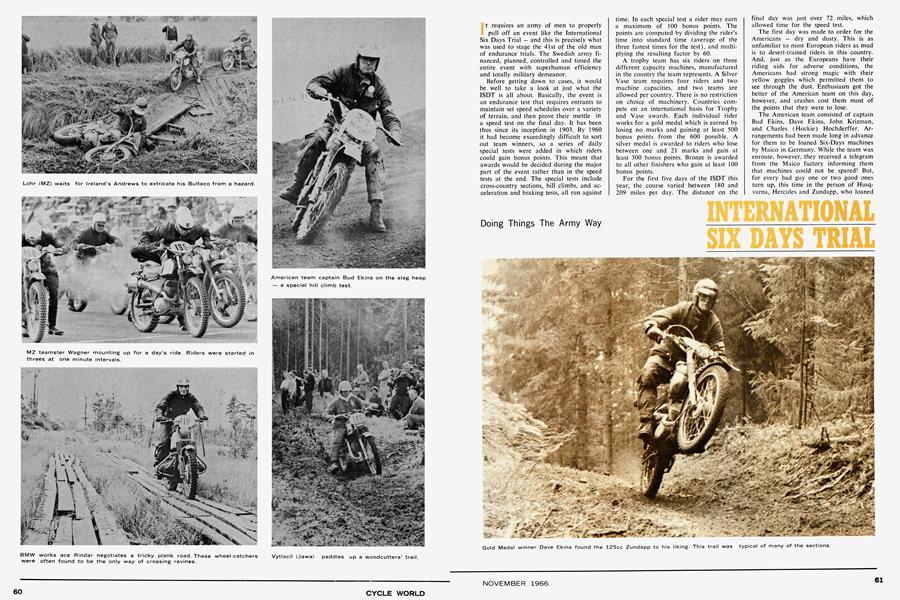

INTERNATIONAL SIX DAYS TRIAL

Doing Things The Army Way

IT requires an army of men to properly pull off an event like the International Six Days Trial — and this is precisely what was used to stage the 41st of the old man of endurance trials. The Swedish army financed, planned, controlled and timed the entire event with superhuman efficiency and totally military demeanor.

Before getting down to cases, it would be well to take a look at just what the ISDT is all about. Basically, the event is an endurance test that requires entrants to maintain set speed schedules over a variety of terrain, and then prove their mettle in a speed test on the final day. It has been thus since its inception in 1903. By 1960 it had become exceedingly difficult to sort out team winners, so a series of daily special tests were added in which riders could gain bonus points. This meant that awards would be decided during the major part of the event rather than in the speed tests at the end. The special tests include cross-country sections, hill climbs, and acceleration and braking tests, all run against

time. In each special test a rider may earn a maximum of 100 bonus points. The points are computed by dividing the rider’s time into standard time (average of the three fastest times for the test), and multiplying the resulting factor by 60.

A trophy team has six riders on three different capacity machines, manufactured in the country the team represents. A Silver Vase team requires four riders and two machine capacities, and two teams are allowed per country. There is no restriction on choice of machinery. Countries compete on an international basis for Trophy and Vase awards. Each individual rider works for a gold medal which is earned by losing no marks and gaining at least 500 bonus points from the 600 possible. A silver medal is awarded to riders who lose between one and 21 marks and gain at least 300 bonus points. Bronze is awarded to all other finishers who gain at least 100 bonus points.

For the first five days of the ISDT this year, the course varied between 180 and 209 miles per day. The distance on the

final day was just over 72 miles, which allowed time for the speed test.

The first day was made to order for the Americans — dry and dusty. This is as unfamiliar to most European riders as mud is to desert-trained riders in this country. And, just as the Europeans have their riding aids for adverse conditions, the Americans had strong magic with their yellow goggles which permitted them to see through the dust. Enthusiasm got the better of the American team on this day, however, and crashes cost them most of the points that they were to lose.

The American team consisted of captain Bud Ekins, Dave Ekins, John Krizman, and Charles (Hockie) Hochderffer. Arrangements had been made long in advance for them to be loaned Six-Days machines by Maico in Germany. While the team was enroute, however, they received a telegram from the Maico factory informing them that machines could not be spared! But, for every bad guy one or two good ones turn up, this time in the person of Husqvarna, Hercules and Zundapp, who loaned machinery to the Yanks. With one exception the machines were properly prepared and ready to go the distance. Krizman’s 250cc Husqvarna had been used in several endurance meets, and was then pressed into service for laying the course. John retired on the third day with ignition trouble while still in contention for a silver medal.

Hercules, by the way, was delighted to loan one of their very special ISDT mounts to a man named Hochderffer, regardless of the country he represented. And Hockie gave them fair value for their money, riding smoothly to a silver medal. While the Americans may have had an advantage on the first day it was hardly noticeable, for few Europeans lost marks. Four of the Vase teams lost a rider apiece, and two retirements were brought about by accidents.

Stacked up against last year’s Isle of Man course, the ’66 ISDT was easy. Much of the course was run over fast dirt roads. The tough sections, however, remained true to ISDT tradition and were very tough. In the main, these consisted of muddy woodcutters’ trails, generously endowed with rocks and tree roots, and while these proved to be the most difficult sections for the Americans, the lesson in restraint and concentration learned on the first day put them in good stead.

Possibly because it has been some time since they have won an International Trophy, the British teams were a bit slow to believe that they had a chance for it this year. By the time they discovered their potential, the die had been cast — the East German team was convinced of their chances from the start. The MZ win was obviously one based on rider skill. The machines were unremarkable, if well-prepared and correctly rigged. This was true of the overall picture this year, with the bulk of the machinery being proven articles. One point is evident, however; the multi-speed lightweights have reached a stage in development that ensures their continued popularity for this type of contest. They were easily the equal of the large displacement bikes and gave no quarter.

The Soviets were as bad as the Germans were good. Their lack of skill, absence of spirit, and general clumsiness were very much out of place.

For next year we can look forward to seeing an English team that has been given new hope. Their fight will be a tough one, though, because they are going to have to unseat an East German team that will be looking for that record-breaking fifth consecutive win. We can also expect to see a determined American team, invigorated by two gold medals (Bud and Dave Ekins) and two silvers (Charles Hochderffer and Malcolm Smith). It’s unfortunate that the U. S. does not produce motorcycles that are suited to this type of competition, but perhaps if the gentlemen from Milwaukee were to put their heads together, they could find the potential in some of their lightweights to warrant the modification effort for setting up some “one-off” mounts for an International team. The most essential ingredient already exists — competent riders who are willing to put forth the effort to bring some of the gold home.