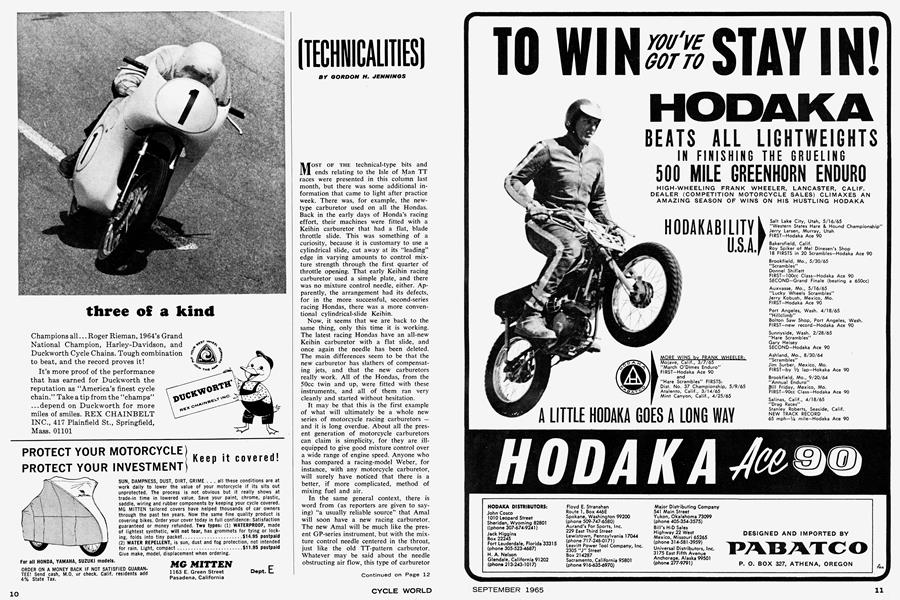

(TECHNICALITIES)

GORDON H. JENNINGS

MOST OF THE technical-type bits and ends relating to the Isle of Man TT races were presented in this column last month, but there was some additional information that came to light after practice week. There was, for example, the newtype carburetor used on all the Hondas. Back in the early days of Honda’s racing effort, their machines were fitted with a Keihin carburetor that had a flat, blade throttle slide. This was something of a curiosity, because it is customary to use a cylindrical slide, cut away at its “leading” edge in varying amounts to control mixture strength through the first quarter of throttle opening. That early Keihin racing carburetor used a simple plate, and there was no mixture control needle, either. Apparently, the arrangement had its defects, for in the more successful, second-series racing Hondas, there was a more conventional cylindrical-slide Keihin.

Now, it seems that we are back to the same thing, only this time it is working. The latest racing Hondas have an all-new Keihin carburetor with a flat slide, and once again the needle has been deleted. The main differences seem to be that the new carburetor has slathers of compensating jets, and that the new carburetors really work. All of the Hondas, from the 50cc twin and up, were fitted with these instruments, and all of them ran very cleanly and started without hesitation.

It may be that this is the first example of what will ultimately be a whole new series of motorcycle racing carburetors — and it is long overdue. About all the present generation of motorcycle carburetors can claim is simplicity, for they are illequipped to give good mixture control over a wide range of engine speed. Anyone who has compared a racing-model Weber, for instance, with any motorcycle carburetor, will surely have noticèd that there is a better, if more complicated, method of mixing fuel and air.

In the same general context, there is word from (as reporters are given to saying) “a usually reliable source” that Amal will soon have a new racing carburetor. The new Amal will be much like the present GP-series instrument, but with the mixture control needle centered in the throat, just like the old TT-pattern carburetor. Whatever may be said about the needle obstructing air flow, this type of carburetor is used by Yamaha, Suzuki, MV and just about everyone who is not using the present type of GP Amal, and it cannot be said that machines fitted with center-needle carburetors appear handicapped in terms of power output compared to those fitted with remote needle carburetors.

Continued on Page 12

Regardless of needle position, there is reason to believe that carburetors without metering needles will give better mixture control. Weber, in Italy, have demonstrated with their racing carburetors that exceedingly precise metering, over a wide engine speed range, can be obtained with only fuel and air-correction jets, and different types of “emulsion” chambers.

In point of fact, the primary mixture control in carburetors having metering needles is provided by balancing a main-jet and air-correction jet; the needle is there as an over-riding control for part-throttle running and plays no part in mixture strength at full throttle. So, it would seem that Honda’s associate, Keihin, has chosen to make the primary mixture system somewhat more precise, and to handle part-throttle conditions with compensating jets. If this type carburetor does not become more popular, in racing applications at least, it will only be because of the boxes upon boxes of jets and emulsion blocks necessary for tuning.

There is the possibility, of course, that there will be a technological jump to carry us from the present adequate, if somewhat crude, carburetor right over to fuel injec-

tion. Fuel injection is doing quite a good job in racing cars, and most people are of the opinion that it is the coming thing for motorcycles. I have some reservations about this. Proponents of fuel injection are inclined to overlook the fact that horsepower gains with injection are slight, and have in most instances been purchased at the expense of wide-range power.

Actually, it is probable that fuel injection has become popular in racing cars simply due to improvement in tires. Obscure reasoning? Not at all. With advances in racing tire design, cornering power has increased to the extent that cars will build to well beyond one “G” of side force; I am told that the Indianapolis Lotus will pull nearly 1.25 Gs in the corners. Given side loads of that magnitude, it is all but impossible to make float chambers behave properly. Fuel will climb up on the side of the chamber, and may leave one or more of the jets high and dry. Or, the sideloads imposed by cornering may tend to dump extra fuel into the engine. In either case, the engine cannot run cleanly. Fuel injection, on the other hand, is unaffected by cornering loads and that is, I think, the primary reason for its widespread use in racing automobiles. The racing motorcycle, which is banked over in the turns and thus feels no side loads, as such, does not impose that kind of outrageous conditions on its float chambers and the advantages in going to fuel injection would therefore be less pronounced. Also, when dealing with very small unit cylinder displacements (each cylinder in the Honda 250cc six accounts for only 41cc), the quantity of

fuel injected into each cylinder, in a single intake stroke, is so small that the most minute errors in fuel delivery volume become serious variations in mixture strength.

Ignition problems were not so much a problem at this year’s TT races as in 1964, but that does not mean the problem no longer exists, or that it is no longer serious. I suppose it would be most correct to say that the problem has been reduced to the extent that some of the factory teams have found solutions. MZ team-boss Walter Kaaden has had to deal with misfiring that persists through several complete changes of ignition systems. Even transistorized Lucas equipment, made to order, has not had much effect on this particular bother. Suzuki, too, has been in difficulty, and plug-fouling almost certainly cost them a 125-class win at the Island. They were beaten by the very new and relatively undeveloped 125 Yamaha, which was not quite as fast, but did not have to stop for a change of spark plugs.

Both two-stroke and four-stroke engines have been troubled by ignition system malfunctions, mostly because the modern “multi” requires such a fantastic number of sparks per minute. However, it seems to be more difficult to overcome in two-strokes. These engines, firing at twice the rate of a four-stroke (at the same engine speed) give their spark plugs no rest, and rather cold plugs are needed to cope with the heat at full throttle. Unfortunately, the plugs must often be so cold that they tend to foul when the engine is being run at part throttle, when not enough heat is being generated to keep them burned clean.

Continued on Page 14

The two-stroke engine further aggravates the situation bv having relatively large quantities of oil being fed up into the combustion chamber. But, interestingly enough, the tendency to foul plugs will vary in ways not explained by specific power-output or the plug heat-range involved. Apparently, the porting in some two-strokes tends to gather up gobs of oil and deposit them on the plug; in others, the oil seems to be directed away from the spark plug. The very fact that some do, while others do not is another sure indication that the two-stroke’s behavior is imperfectly understood — at best. Or, it may also mean that those factories not troubled by plug fouling actually do understand what this phase of two-stroke design is all about, but are not saying.

The least troublesome aspect of the motorcycle, racing or otherwise, is its tires. These will wear out, but the days when one could also occasionally expect to lose chunks of tread are gone. Gone too are the skids and slides on wet roads; modern rubber compounds and tread patterns have overcome that. (Up to a point, of course.) Most important, modern tires have (I think) just about eliminated the dread “speed wobble,” which at one time accounted for many a case of asphalt-rash. If you talk to the old-time “runners” from the Isle of Man, you will hear many a tale of speed wobbles on the mountain circuit. In recent years, this phenomenon has virtually disappeared and it is very likely that credit for the improvement can go to the tires now being made.

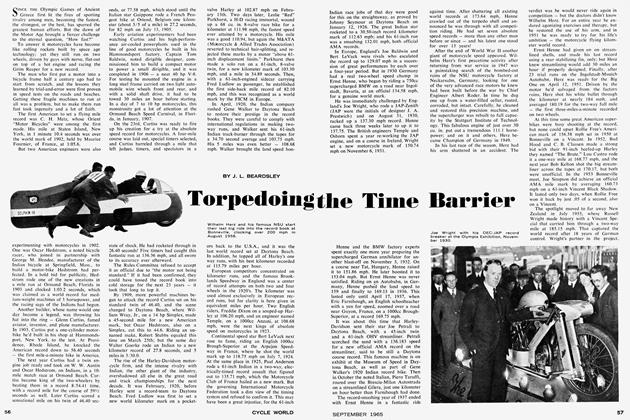

While on the subject of tires, mention must be made of the new road racing tires from Goodyear. These tires first came to our attention at Daytona, where they were being used by the Harley-Davidson team and assorted others. It seemed, watching the bikes fitted with Goodyear racing tires, that they were most definitely under no handicap in cornering. Still, being rather conservative about such things, we reserved judgment until such time as we could gather some first-hand experience.

This experience came recently when a set of Goodyears were fitted on my Yamaha TD-1B, and I tried them in a race at Willow Springs. After a single race. I am reluctant to say that the Goodyear road racing tires are better than those from Dunlop (the only other company making “real” road racing tires); but they certainly seem to be at least as good. It is my impression (and that of John Buckner, also racing a Yamaha on Goodyears) that the Goodyear tires tend to run at a slightly greater slip-angle when cornering, which means that one’s machine “drifts” slightly more when using them.

Also, on the basis of having gotten into, and out of, a dandy slide, I would say that “breakaway” occurs a bit more gently than with other tires. Buckner has used the Goodyear tires in the rain, and says they are not bothered much by water, and he is getting really phenomenal tire wear: five full race meetings, accounting for at least 600 racing miles, and there is still plenty of tread left. More will be said on the subject of wear later, as I am keeping records of miles and tread depth on my tires.

As a parting shot this month, I will unburden my soul of something that galls me terribly. Foreign manufacturers with fullscale teams in International racing have not, as yet, given a spot on their teams to an American rider. It can, of course, be said that we have no riders sufficiently talented; but anyone who says that is quite wrong. True, those men who now hold places with the factory teams are superb riders. But, anyone who thinks they are some sort of supermen, who only grow to full stature in Europe’s clammy air, is sadly mistaken. Phil Read and Mike Hailwood are, by virtue of tremendous natural talent and a wealth of experience, probably the world’s best. However, it is entirely possible that we have riders who could develop into their equal, given the opportunity. Jody Nicholas has about as much talent as you are likely to find, and so does Tony Murphy. To this list of potential road racing greats I would also add Ralph White, Dick Mann, and I am sure there are others. In any case, I have just named one really exceptional rider (by any standard; ours or England’s) for the Honda, Yamaha and/or Suzuki works teams. As riders, I think these men deserve the break; as Americans, who buy a lot of these manufacturers’ (and others) motorcycles, we should be given this sort of representation in factory team-level racing. It would be a good thing all around.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue