INTERNATIONAL SIX DAYS TRIAL

HEINZ SCHNEIDER

SUMMER IS GONE - and the season almost over, when top-flight rough-riders gather to compete in an annual oneweek enduro, the International Six Days Trial.

Politics from club levels to the international ones had kept West Germans and the much fancied Italian riders out this year. Nevertheless. 226 competitors had their bikes scrutinized by the weekend, and vital parts were marked and stamped to prevent any exchange of broken-down machinery. At the shocking time of fivethirty in the morning, when daylight just crept over the mountains of Thuringer Wald, the first riders took their mounts out of the closed paddock. Regulations give them only ten minutes to get the bikes ready, and after the starter has sent a man on his way, he has another minute to kick the cold engine into life and cover twenty meters under power. If he fails to start within this limit, he will lose twenty bonus points.

Once under way. he has to keep a set average which depends on the engine capacity. So the rider follows the arrows which mark out the course, getting his route-card stamped in a couple of places to assure he has not taken a short cut. Keeping an eye on his clock and the mileage-counter, he can adjust his speed

to hit the time check on the right minute. There the time is stamped on his card. If he is late, he will lose one mark a minute outside a three-minute allowance. Once the record is spoiled the gold medal is gone.

If one has time in hand before such a check it may be spent on the bike, adjusting the chain, changing a punctured tube (which usually can be done within three minutes) or hammering bent bits anti pieces straight again. Sooner or later there is a special test, a patch of scrambling, road race or a drag-strip run. Here the rider tries as hard as he can. because it is the chance to collect bonus points. Fastest man is credited with sixty points, the slower one's shares are figured with his time as basic factor. These bonus points decide ties between riders and teams with no marks lost, so they arc vital.

There is not much chance to practice tests, and what may be done to help a rider do well is not really known. Some managers are good at drawing special maps with distances and possible speeds on it. Some countries put a man at every tricky spot, who shows his riders the way and lets the others disappear in the forest. Some people are not even noticed at all: it is easy to put a red crash helmet at a dangerous place and a green one where the track is clear and just sit there without giving yourself away.

When the day is finally over, riders arrive back where they started from, clock in and leave the bike to the closed paddock officials. Tike that it goes for five days; on the sixth only the morning is spent in the rough. The afternoon’s occupation is a road race — with the same trials bikes and trials tires. A relic from those days when there were no special tests, it is supposed to decide the trial, which usually has been decided already.

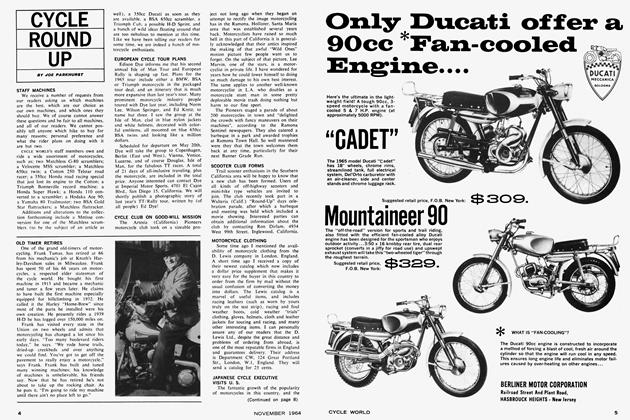

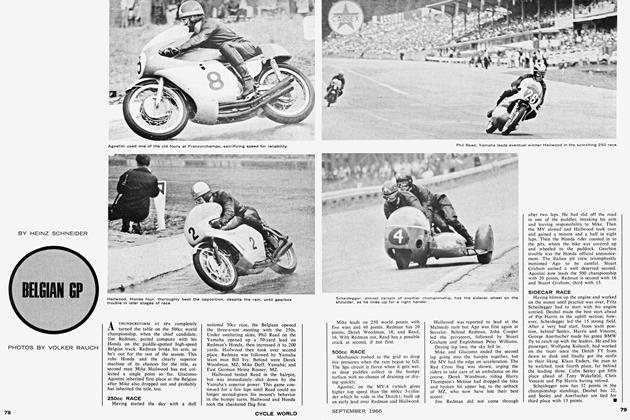

Californian Bud Ekins having been a regular performer for the last two years, the Americans have now stepped in in full force, fielding ten riders, eight of which rode for Vase-Teams.

Just a word on teams. The Trophy is the big pot every country is after because of its top value in advertising. Six-man teams on bikes produced by national manufacturers enter in three different classes. There may be only one trophy team entered per country. Two or four strong ones may be fielded to compete for the Silver Vase. Here it is of no importance where the bikes are made. So countries with no competitive motorcycle industry have a chance to go for top honors.

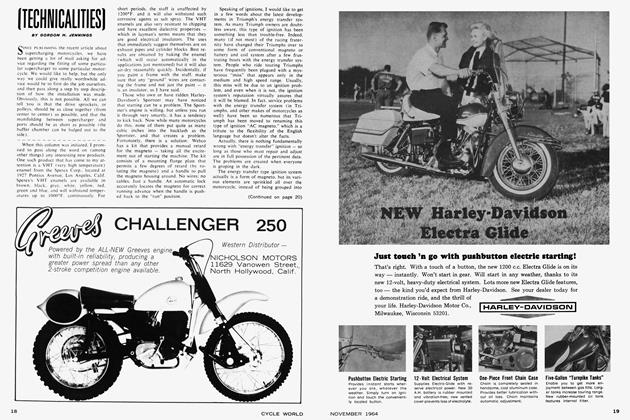

That is w'hat Bud and brother Dave Ekins. Cliff Coleman and Hollywood actor Steve McQueen did on 500 and 650cc Triumphs they had just collected in England and modified to their liking. Modifications. by the way. must have been excellent; the American-ridden bikes gave a much smoother impression than the Triumphs of Ken Heanes and John Giles, members of the British Trophy Team.

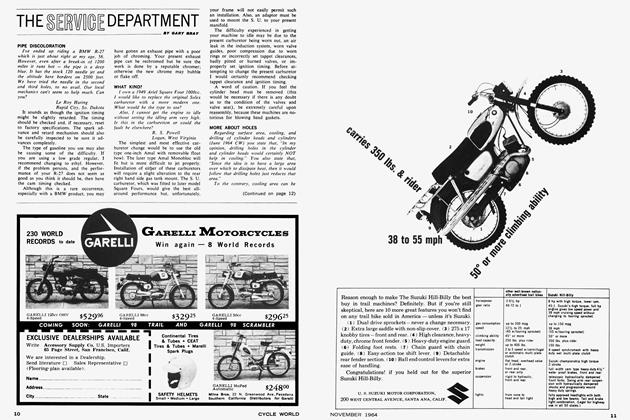

Dave and Cliff lasted the event with no marks lost on time, so they collected gold medals. Unfortunately Bud broke a leg in one of the many crashes American riders w'ere involved in. Steve, after repairing a broken chain, was last man on the road at the end of the third day. A local motorcyclist, thinking riders had all come past, blocked his way and sent him off into a ditch, where the Triumph’s forks folded under the frame. Fifth American in the big class was John Steen, who had another Triumph 500 as single entry. Having lost 13 marks the very first day after losing his way, he maintained clean sheet thereafter and walked off with a silver medal.

In the smaller capacity, the CzechCZ factory fielded four of their unlucky new 175 and 250 bikes for a second American Vase team. Stewart Peters retired the first day (he had a Jawa, no CZ) with a seized-up engine. Paul Hunt injured a leg. and the carburetor flange of John Smith’s CZ 250 broke. That left only William Steward in the game. First day the points on his 175 CZ closed up, result of somebody’s forgetfulness in tightening up nuts and bolts. By the time he found this cause, with fingers trembling in the cold morning rain, twenty-one minutes had elapsed, and the gold medal was gone.

East Coast Bultaco importer John Taylor had a fairly trouble-free run on a newly acquired 175 Bultaco. but now and then the clock beat him on speed and regularity. So John collected a bronze medal only.

Despite John’s trouble with the clock, this year’s course was regarded as the easiest for years, and regular contenders were found with plenty of time in hand at timechecks. This was due to the organizers’ luck — or bad luck — with the weather. For the first three days it rained; the second morning there was even fog. But then skies brightened, the sun came through and stony paths through the mountains were easy going. Had it rained all the time, as is usual at this time of the year, mud would have brought riders real trouble.

Only 62 of the 226 starters retired during the week. 121 collected a gold medal 31 a silver one and 12 were given bronze, which are unusually high figures. Despite the low retirement rate, all Trophy Teams except the English and the East German were jinx-stricken.

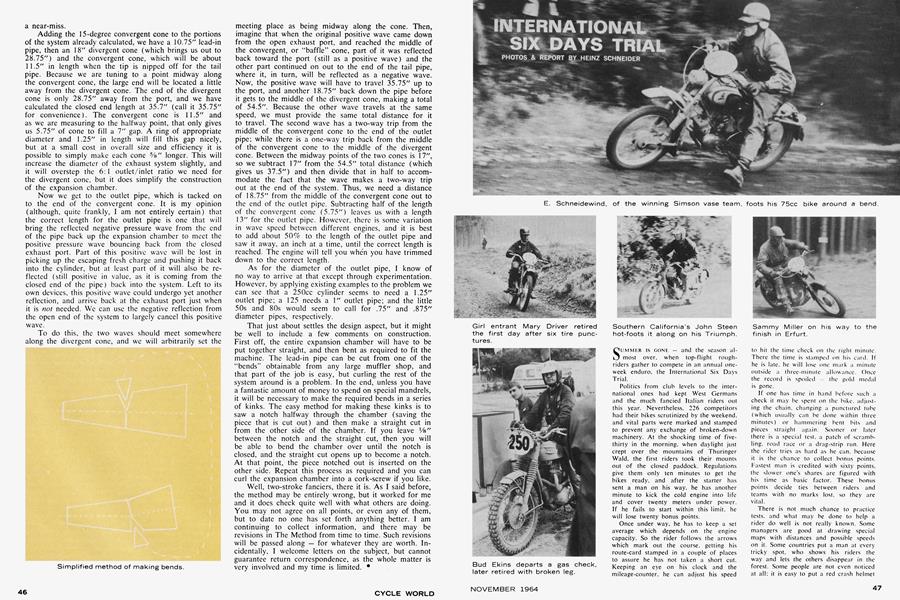

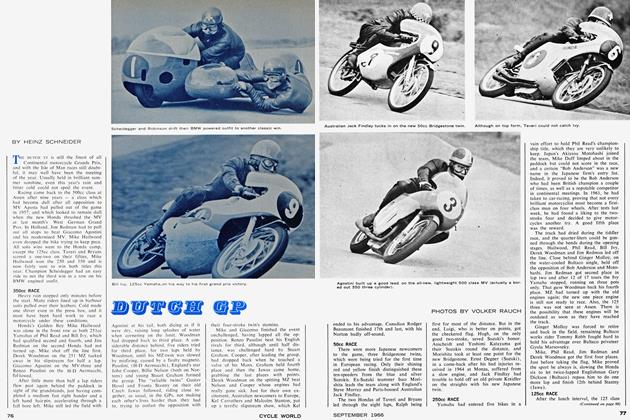

Having the trial in their country for the first time. East German factories — (MZ with motorcycles of bigger capacity and Simson with fifties and seventy-fives) had started an all-out effort to sweep the board. MZ fielded last year’s winning team for the Trophy, and four other strong men for the Vase. Simson’s top liners formed the second Vase team.

In countries with a more complex motor industry, like England, the advertising value of ISDT successes results in timeconsuming arguments over selection of makes and riders for the teams. In Socialist countries, where orders work wonders, this time is spent on preparation of machines named for the event.

The Czechs this year formed an exception to the rule. With both Jawa and CZ being talked about, there is now competition between these makes. The careful line was left - by CZ at least - and untried machines entered in the trial. Trophy riders Valek and Miaka’s gearboxes (new five or six-speed ones, there were different announcements) caused trouble during the third day and put the favorites out. Veteran team captain Sacha Klimt crashing the last day and splitting his Jawa’s gearbox case was just bad luck on top of it.

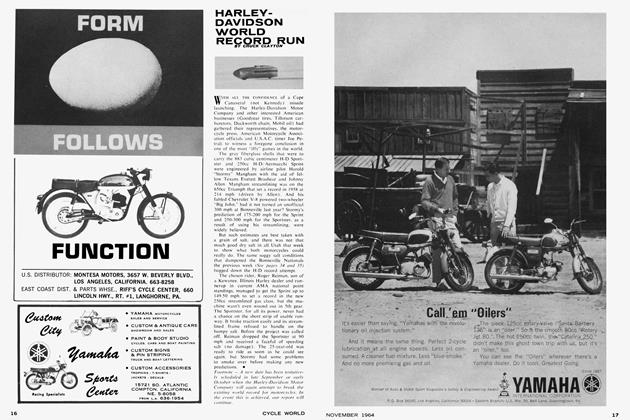

England tried her luck with James Sandiford (BSA 350). Roy Peplow (Triumph 350). J. V. Brittain (500cc Royal Enfield), Sammy Miller (500cc Ariel), and John Giles and Ken Heanes on big Triumphs. The British four-strokes, subject of retirements for many reasons during the last years, lasted the course well but during the special tests twostrokes beat them by lengths.

So the East Germans, running clean, won the trophy on bonus points. A trick of tactics: MZ had fielded Fred Willamowski, many times scrambles champion, as a single rider in the 500cc class. Riding a 372cc mount he was the big spoiler and robbed the English of their bonus points. Being on no team, he could afford to try hard in the tests, even at risk of wrecking his engine. Lost marks, which he might have collected in succession, would have cost him the medal but his hard riding helped MZ to win the trophy.

Another way of doing well in the tests was seen in winning team leader Werner Salewsky's riding. On a narrow path it is difficult to overtake a slower rider, and losing five seconds on this occasion may influence the whole day’s results. So Werner just took it easy on the approach to the start, and had the way clear ahead of him to press on and set fastest time.

Coming up steadily, but still not knowing how to ride the ISDT, are the dicers from Sweden and Russia. Both appear

to have more scrambles experience than the enduro type, and they dash through the country accordingly.

A Swedish Trophy rider. B. Sjosvard, dropped his 250 Husqvarna the first day and broke a leg. A retired rider charges his team with 100 lost marks a day, so a Trophy man should take better care of himself and try to avoid damage, as the British riders showed this year. Nevertheless. the Swedes finished fourth behind the Russians, who put up a terrific show this year. The first day their rider. Kirsis, lost three marks when punctures hit him, and during the fourth he retired with a broken rear brake. W. Darwin, like the other Russian Trophy members on an Isch two-stroke, also lost three marks; that was all they had to contend with.

The Czechs, and their bad luck — or bad preparation — have been mentioned. Sixth team home were the Poles. They had left their scooters at home this time and started on WSK and WFM twostrokes, and on the Junak, tested in CYCLE WORLD. Seventh, and last, were the onetime Trophy winners from Austria. First day had put their Puch 250 rider Behrendt out. with a cable broken inside its insulation. J. Sommerauer, on a KTM 50cc followed when he bent his front fork in a crash, and T. Kiemswenger. on a 125cc KTM broke the front rim when traveling with a flat tire.

There is a snag with these spare tubes that all riders carry. Some tie them to the bike with rubber straps and think it is all right. After a day in mud, dust

and sand, so much dirt has collected on the tube that it is not usable to replace a punctured one. Sand will grind through the rubber and, after a couple of miles, cause a second puncture. A nylon bag is an investment that pays off.

Cat among the pigeons with Silver Vase riders were the Finns, on Jawa and MZ machinery. "Eyes closed, the throttle fully open” you could see the hlack-helmeted chaps dash through the special tests. A broken frame on his Jawa put P. Karaha out on the fourth day. and so pushed the best Finnish team from second place. The way then was clear for the Fast German Simson and MZ riders. Simsons w'on with only 34 bonus points on the MZ riders.

Manufacturers prize went to MZ. They took all class wins, except the 125 where a Czech on a CZ won; the 750, where they did not enter, w'ent to the Fast Germans. Only the Club Team prize went w'est, to Holland, to three riders mounted on West German bikes.

This out and out success of the East Germans cannot be described as due to a course specially suited to MZ’s need. It is the result of a supreme effort to win which is only possible in a country needing success in sport and willing to invest some money. It also is a result of British machinery being comparatively years behind where power output is concerned, and a result of unwise strategy by the CZ team.

Maybe with the strong Italians and West German riders in the game. MZ would have to fight harder. •