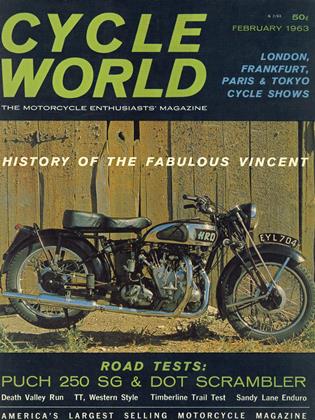

TT WESTERN STYLE

CAROL A. SIMS

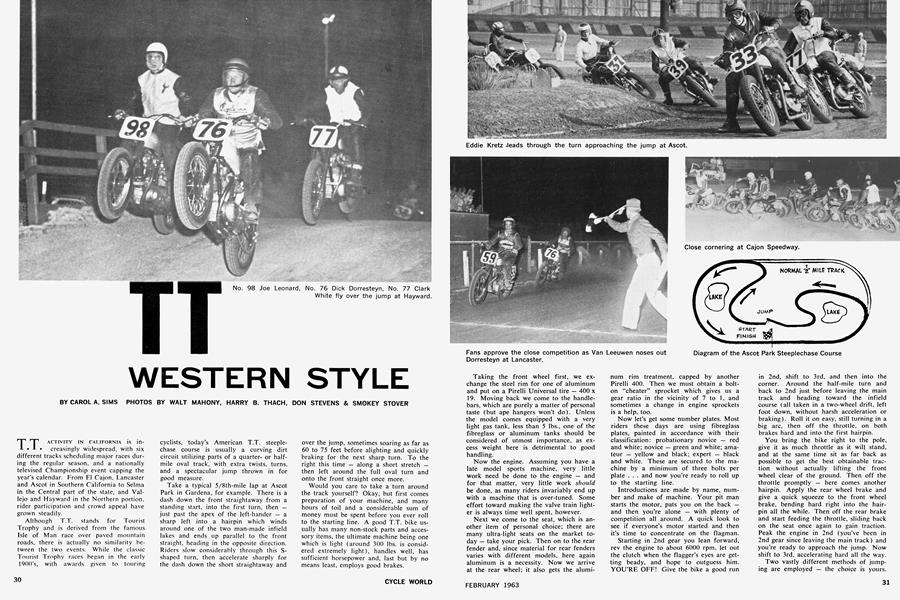

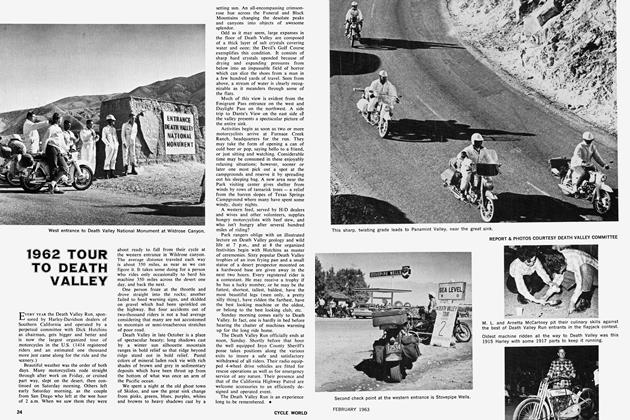

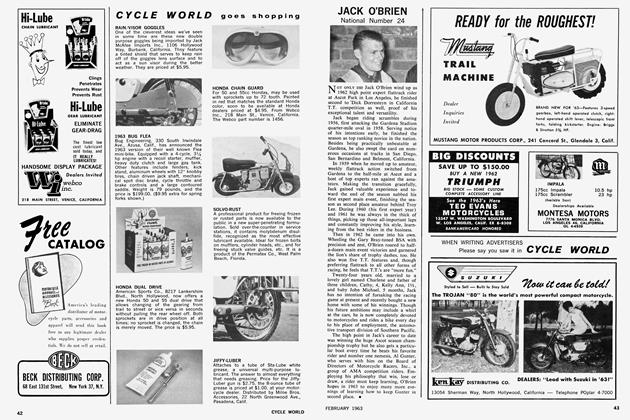

T.T. ACTIVITY IN CALIFORNIA is increasingly widespread, with six different tracks scheduling major races during the regular season, and a nationally televised Championship event capping the year's calendar. From F.1 Cajon, Lancaster and Ascot in Southern California to Selma in the Central part of the state, and Vallejo and Hayward in the Northern portion, rider participation and crowd appeal have grown steadily.

Although T.T. stands for Tourist Trophy and is derived from the famous Isle of Man race over paved mountain roads, there is actually no similarity between the two events. While the classic Tourist Trophy races began in the early 1900's, with awards given to touring cyclists, today's American T.T. steeplechase course is usually a curving dirt circuit utilizing parts of a quarteror halfmile oval track, with extra twists, turns, and a spectacular jump thrown in for good measure.

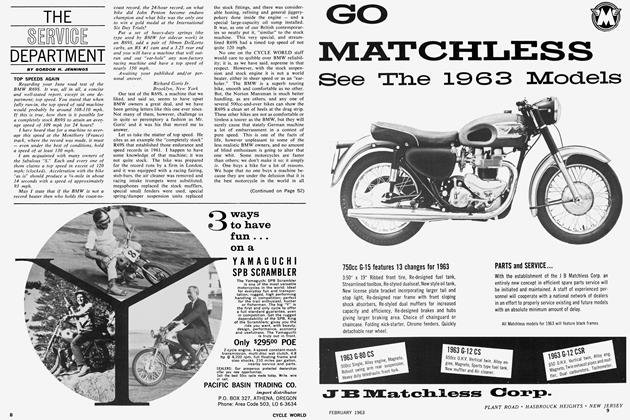

Take a typical 5/8th-mile lap at Ascot Park in Gardena, for example. There is a dash down the front straightaway from a standing start, into the first turn, then — just past the apex of the left-hander — a sharp left into a hairpin which winds around one of the two man-made infield lakes and ends up parallel to the front straight, heading in the opposite direction. Riders slow considerably through this Sshaped turn, then accelerate sharply for the dash down the short straightaway and over the jump, sometimes soaring as far as 60 to 75 feet before alighting and quickly braking for the next sharp turn. To the right this time — along a short stretch — then left around the full oval turn and onto the front straight once more.

Would you care to take a turn around the track yourself? Okay, but first comes preparation of your machine, and many hours of toil and a considerable sum of money must be spent before you ever roll to the starting line. A good T.T. bike usually has many non-stock parts and accessory items, the ultimate machine being one which is light (around 300 lbs. is considered extremely light), handles well, has sufficient horsepower and, last but by no means least, employs good brakes.

Taking the front wheel first, we exchange the steel rim for one of aluminum and put on a Pirelli Universal tire — 400 x 19. Moving back we come to the handlebars, which are purely a matter of personal taste (but ape hangers won't do). Unless the model comes equipped with a very light gas tank, less than 5 lbs., one of the fibreglass or aluminum tanks should be considered of utmost importance, as excess weight here is detrimental to good handling.

Now the engine. Assuming you have a late model sports machine, very little work need be done to the engine — and for that matter, very little work should be done, as many riders invariably end up with a machine that is over-tuned. Some effort toward making the valve train lighter is always time well spent, however.

Next we come to the seat, which is another item of personal choice; there are many ultra-light seats on the market today — take your pick. Then on to the rear fender and, since material for rear fenders varies with different models, here again aluminum is a necessity. Now we arrive at the rear wheel; it also gets the aluminum rim treatment, capped by another Pirelli 400. Then we must obtain a bolton "cheater" sprocket which gives us a gear ratio in the vicinity of 7 to 1, and sometimes a change in engine sprockets is a help, too.

Now let's get some number plates. Most riders these days are using fibreglass plates, painted in accordance with their classification: probationary novice — red and white; novice — green and white; amateur — yellow and black; expert — black and white. These are secured to the machine by a minimum of three bolts per plate . . . and now you're ready to roll up to the starting line.

Introductions are made by name, number and make of machine. Your pit man starts the motor, pats you on the back — and then you're alone — with plenty of competition all around. A quick look to see if everyone's motor started and then it's time to concentrate on the flagman.

Starting in 2nd gear you lean forward, rev the engine to about 6000 rpm, let out the clutch when the flagger's eyes are getting beady, and hope to outguess him. YOU'RE OFF! Give the bike a good run in 2nd, shift to 3rd, and then into the corner. Around the half-mile turn and back to 2nd just before leaving the main track and heading toward the infield course (all taken in a two-wheel drift, left foot down, without harsh acceleration or braking). Roll it on easy, still turning in a big arc, then off the throttle, on both brakes hard and into the first hairpin.

You bring the bike right to the pole, give it as much throttle as it will stand, and at the same time sit as far back as possible to get the best obtainable traction without actually lifting the front wheel clear of the ground. Then off the throttle promptly — here comes another hairpin. Apply the rear wheel brake and give a quick squeeze to the front wheel brake, bending hard right into the hairpin all the while. Then off the rear brake and start feeding the throttle, sliding back on the seat once again to gain traction. Peak the engine in 2nd (you've been in 2nd gear since leaving the main track) and you're ready to approach the jump. Now shift to 3rd, accelerating hard all the way.

Two vastly different methods of jumping are employed — the choice is yours.

Some, when reaching the ramp, back off the throttle and apply the rear brake hard — then off the brake upon leaving the ramp. Riders who leave the throttle off must pull up on the bars to keep the machine in a nose-up position.

Others prefer to accelerate just as they leave the jump, and doing it this way does not require pulling on the bars to keep the front wheel up. The throttle is left off while in mid-air and upon landing (with the rear wheel hitting just before the front) it is turned on again.

Now you accelerate down the short straight, still in 3rd, then backshift to 2nd and apply both brakes approaching the right .lander. This is a very ticklish 100 degree turn, faster then either hairpin, and the front wheel tends to slip going in, plus the added hazard of a tendency to go wide coming out.

Having completed this tricky little job in good shape you accelerate down the short stretch according to individual preference, or gear ratio, either winding it tight in 2nd gear or making a shift to 3rd, then going back immediately to 2nd and on with both brakes upon nearing the half-mile oval again. Here the left foot goes down as you make the short left hander onto the main track. Accelerate in 2nd. and 3rd, then just as you bend it hard to make the big turn, into 4th (although some riders prefer to run it all the way around the turn in 3rd, hitting 4th on the front straightaway, dependent upon their gear ratios).

Now it's under the paint to cheat the wind and down the front straightaway, staying toward the outside of the track, next to the wall. Man, this is FAST — these big bikes accelerate to over 90 mph on the front stretch — and making your corner approach takes considerable skill and judgment. Now off the throttle and on with both brakes as you near the south turn. When you are far enough around the turn to see where the T.T. course leaves the main track, shift down to 3rd, then to 2nd in quick succession and — you've made a lap at Ascot!

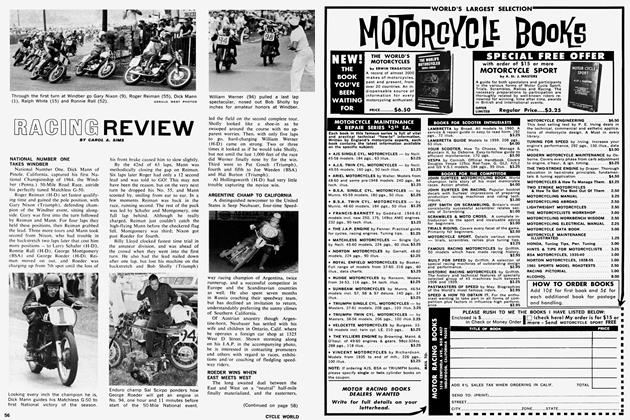

Having ridden the track yourself, it's easy to see why this and similar courses are so demanding upon both rider and machine, and the extreme challenge makes for keen spectator interest as well. Leading exponent of the T.T. sport these days is Dick Dorresteyn from San Pablo, California. Seldom, if ever, has there been a blending of man and machine to equal the Dorresteyn/Triumph combination; he is truly a natural, as his competitors will be quick to agree.

But competition he has — primarily in the form of such dauntless foes as Jack

O'Brien, Clark White, Dick Hammer, Skip Van Leeuwen, Jack Simmons, Joe Leonard and Sid Payne, all winners in 1962, though many up-and-comers are moving rapidly through the ranks.

Hot California amateurs who will be riding as experts in 1963 include Clyde Litch, Elliott Schultz and Mert Lawwill; each is an all-around rider and will bear close scrutiny throughout the coming season. Moving to amateur is Eddie Mulder, who has had things pretty much his own way in the novice division, though Bob Bailey is no stranger to the El Cajon winner's circle and another boy to watch is young Mel Lacher from San Diego.

With ever-increasing rider turnouts and growing crowd appeal, 1963 should be the most successful year yet for T.T. racing, not only in California but throughout the United States. •

View Full Issue

View Full Issue