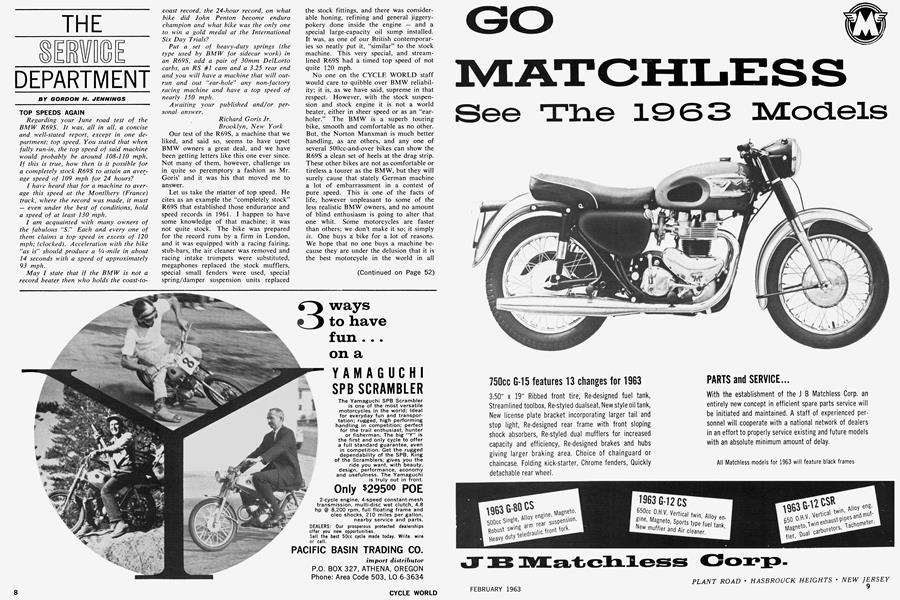

THE SERVICE DEPARTMENT

GORDON H. JENNINGS

TOP SPEEDS AGAIN

Regarding your June road test of the BMW R69S. It was, all in all, a concise and well-stated report, except in one department; top speed. You stated that when fully run-in, the top speed of said machine would probably be around 108-110 mph. If this is true, how then is it possible for a completely stock R69S to attain an average speed of 109 mph for 24 hours?

I have heard that for a machine to average this speed at the Montlhery (France) track, where the record was made, it must — even under the best of conditions, hold a speed of at least 130 mph.

I am acquainted with many owners of the fabulous "S." Each and every one of them claims a top speed in excess of 120 mph; (clocked). Acceleration with the bike "as is" should produce a V4-mile in about 14 seconds with a speed of approximately 93 mph.

May I state that if the BMW is not a record beater then who holds the coast-tocoast record, the 24-hour record, on what bike did John Penton become enduro champion and what bike was the only one to win a gold medal at the international Six Day Trials? Put a set of heavy-duty springs (the type used by BMW for sidecar work) in an R69S, add a pair of 30mm DelLorto carbs, an RS #1 cam and a 3.25 rear end and you will have a machine that will out run and out "ear-hole" any non-factory racing machine and have a top speed of nearly 150 mph. A waiting your published and/or per sonal answer.

Richard Goris Jr. Brooklyn, New York Our test of the R69S, a machine that we liked, and said so, seems to have upset BMW owners a great deal, and we have been getting letters like this one ever since. Not many of them, however, challenge us in quite so peremptory a fashion as Mr. Goris' and it was his that moved me to answer.

Let us take the niatter of top speed. He cites as an example the "completely. stock" R69S that established those endurance and speed records in 1961. I happen to have some knowledge of that machine; it was not quite stock. The bike was prepared for the record runs by a firm in London, and it was equipped with a racing fairing, stub-bars, the air cleaner was removed and racing intake trumpets were substituted, megaphones replaced the stock mufflers, special small fenders were used, special spring/damper suspension units replaced the stock fittings, and there was consider able honing, refining and general jiggery pokery done inside the engine - and a special large-capacity oil sump installed. It was, as one of our British contemporar ies so neatly put it, "similar" to the stock machine. This very special, and stream lined R69S had a timed top speed of not quite 120 mph.

No one on the CYCLE WORLD staff would care to quibble over BMW reliabil ity; it is, as we have said, supreme in that respect. However, with the stock suspen sion and stock engine it is not a world beater, either in sheer speed or as an "ear holer." The BMW is a superb touring bike, smooth and comfortable as no other. But, the Norton Manxman is much better handling, as are others, and any one of several 500cc-and-over bikes can show the R69S a clean set of heels at the drag strip. These other bikes are not as comfortable or tireless a tourer as the BMW, but they will surely cause that stately German machine a lot of embarrassment in a contest of pure speed. This is one of the facts of life, however unpleasant to some of the less realistic BMW owners, and no amount of blind enthusiasm is going to alter that one whit. Some motorcycles are faster than others; we don't make it so; it simply is. One buys a bike for a lot of reasons. We hope that no one buys a machine be cause they are under the delusion that it is the best motorcycle in the world in all respects and in every kind of use — there is no motorcycle that fills that description; not even the BMW.

(Continued on Page 52)

ENGINE BALANCE

I read with interest your article on engine balance in the September issue of CYCLE WORLD.

You seem to have covered about every type of engine design which has appeared on motorcycles and gave the advantages and disadvantages which the design had.

Around 1946, the Wooler "beam" appeared although production for the commercial market never started for this machine. It had a transversely-mounted, horizontally opposed four cylinder engine with one cylinder atop the other with a vertical crankshaft. I was interested in how an engine of this type would rate as far as achieving good balance. I have never seen a design of this type on any other machine.

Mike Gerald Edmond, Oklahoma

Beam type engines, of which the Wooler design was one of the better examples, have been tried many times; none of them has ever scored much of a success. If memory serves me correctly, the Wooler engine did not have a vertical crankshaft; it was mounted horizontally, at right angles to the bores, just like any other crankshaft. However, it was located well below the cylinders, and was connected to the pistons through a system of bell-cranks and walking beams.

Being an opposed four, the Wooler engine would almost certainly have had very good balance, but I am of the opinion that the layout was selected mostly to allow the vertical stacking of cylinders. In this way, all of the cylinders were well exposed to the direct air stream (just like a pair of vertical twins laid over on their sides) and cooling problems were avoided.

The cooling problems were solved, but no solution has as yet been found to the problems created by the inertia of those walking beams, bell-cranks and extra connecting rods. These increase the cost and weight of a beam-type engine, relative to a comparable conventional design, and the high reciprocating forces that are inevitable in so much flailing machinery limit engine speed.

In certain low-speed heavy-duty twostrokes, with pistons paired and working crown to crown in shared cylinders, there is some justification for the use of the "beam" layout; otherwise, it is intriguing but impractical.

HONDA HOP-UP

I own a '62 Honda 305, model CA 77E. Not desiring to race, I do wish to increase performance.

Is porting and increasing jet size recommended? And what else could be done without becoming too costly? Will the engine withstand higher temperatures and rpm?

Lane Mead

China Lake, California

The solution to your problem is so simple I blush to suggest it. Why not borrow the various parts from the CB 77 that go to make up its power edge over the CA 77? Probably, the only difference is in carburetion and compression ratio, and any Honda dealer can consult his parts list and give you the appropriate equipment in short order and at a moderate cost. Then, if you want still more power, there are things like Webco valve-spring and keeper kits to help boost the output even further.

One word of caution: do not attempt too much in porting the cylinder head. These ports are precision cast and it is very difficult to work much of an improvement on the stock condition. Just match the manifold edges carefully to the ports.

Finally, do not expect a really large increase no matter what you do (short of supercharging). The Honda engine is very highly tuned even in completely stock form and no amount of fiddling is going to get drastically more power from it. You can get about 30 bhp from the engine (which is not bad for 19 cubic inches); don't be greedy.

As an aside, I might mention that fully 1/3 of all the inquiries chat come to me concerning engine hop-up work can be answered in a similar manner. Very often, parts from newer and more powerful, or simply more powerful, models of a line can be transferred to older, or milder, bikes for increases in power output. This method is not entirely without its pitfalls; but any dangers that might be encountered through this line of action pale into insignificance compared with the consequences that all too often come from amateur speed-tuning efforts. By borrowing parts, we can "use" the engineering talent and development facilities of the companies that manufacture our bikes, and that is a much safer, if less spectacular and interesting, course than hit-and-miss experimentation. •