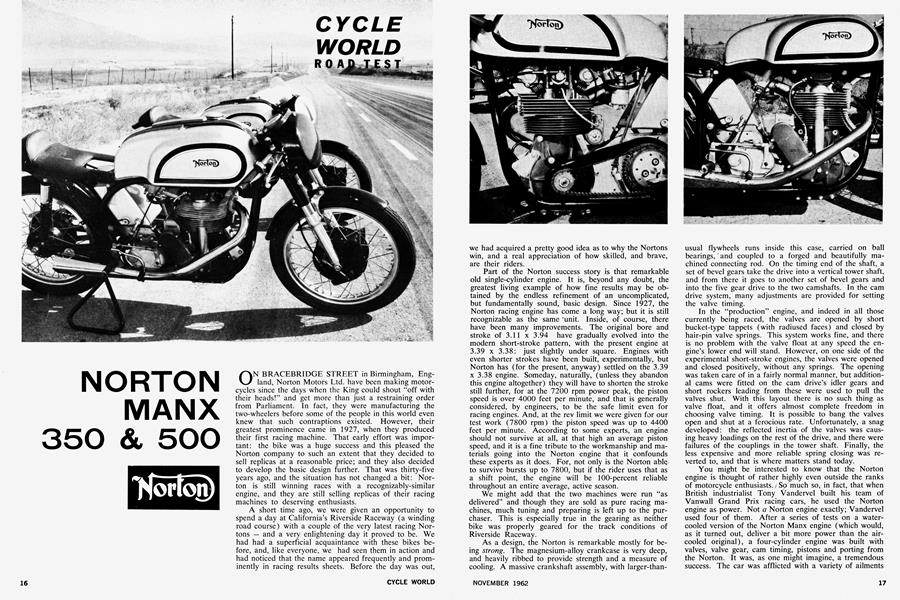

NORTON MANX 350 & 500

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

ON BRACEBRIDGE STREET in Birmingham, England, Norton Motors Ltd. have been making motorcycles since the days when the King could shout "off with their heads!" and get more than just a restraining order from Parliament. In fact, they were manufacturing the two-wheelers before some of the people in this world even knew that such contraptions existed. However, their greatest prominence came in 1927, when they produced their first racing machine. That early effort was important: the bike was a huge success and this pleased the Norton company to such an extent that they decided to sell replicas at a reasonable price; and they also decided to develop the basic design further. That was thirty-five years ago, and the situation has not changed a bit: Nor ton is still winning races with a recognizably-similar engine, and they are still selling replicas of their racing machines to deserving enthusiasts.

Ashort time ago, we Were given an opportunity to spend a day at California's Riverside Raceway (a winding road course) with a couple of the very latest racing Nortons - and a very enlightening day it proved to be. We had had a superficial acquaintance with these bikes be fore, and, like everyone, we had seen them in action and had noticed that the name appeared frequently and prom inently in racing results sheets. Before the day was out, we had acquired a pretty good idea as to why the Nortons win, and a real appreciation of how skilled, and brave, are their riders.

Part of the Norton success story is that remarkable old single-cylinder engine. It is, beyond any doubt, the greatest living example of how fine results may be obtained by the endless refinement of an uncomplicated, but fundamentally sound, basic design. Since 1927, the Norton racing engine has come a long way; but it is still recognizable as the same 'unit. Inside, of course, there have been many improvements. The original bore and stroke of 3.11 x 3.94 have gradually evolved into the modern short-stroke pattern, with the present engine at 3.39 x 3.38: just slightly under square. Engines with even shorter strokes have been built, experimentally, but Norton has (for the present, anyway) settled on the 3.39 x 3.38 engine. Someday, naturally, (unless they abandon this engine altogether) they will have to shorten the stroke still further, for at the 7200 rpm power peak, the piston speed is over 4000 feet per minute, and that is generally considered, by engineers, to be the safe limit even for racing engines. And, at the rev limit we were given for our test work (7800 rpm) the piston speed was up to 4400 feet per minute. According to some experts, an enginô should not survive at all, at that high an average piston speed, and it is a fine tribute to the workmanship and materials going into the Norton engine that it confounds these experts as it does. For, not only is the Norton ablç to survive bursts up to 7800, but if the rider uses that as a shift point, the engine will be 100-percent reliable throughout an entire average, active season.

We might add that the two machines were run "as delivered" and though they are sold as pure racing machines, much tuning and preparing is left up to the purchaser. This is especially true in the gearing as neither bike was properly geared for the track conditions of Riverside Raceway.

As a design, the Norton is remarkable mostly for being strong. The magnesium-alloy crankcase is very deep, and heavily ribbed to provide strength and a measure of cooling. A massive crankshaft assembly, with larger-than-

usual flywheels runs inside this case, carried on ball bearings, * and coupled to a forged and beautifully machined connecting rod. On the timing end of the shaft, a set of bevel gears take the drive into a vertical tower shaft, and from there it goes to another set of bevel gears and into the five gear drive to the two camshafts. In the cam drive system, many adjustments are provided for setting the valve timing.

In the "production" engine, and indeed in all those currently being raced, the valves are opened by short bucket-type tappets (with radiused faces) and closed by hair-pin valve springs. This system works fine, and there is no problem with the valve float at any speed the engine's lower end will stand. However, on one side of the experimental short-stroke engines, the valves were opened and closed positively, without any springs. The opening was taken care of in a fairly normal manner, but additional cams were fitted on the cam drive's idler gears and short rockers leading from these were used to pull the valves shut. With this layout there is no such thing as valve float, and it offers almost complete freedom in choosing valve timing. It is possible to bang the valves open and shut at a ferocious rate. Unfortunately, a snag developed: the reflected inertia of the valves was causing heavy loadings on the rest of the drive, and there were failures of the couplings in the tower shaft. Finally, the less expensive and more reliable spring closing was reverted to, and that is where matters stand today.

You might be interested to know that the Norton engine is thought of rather highly even outside the ranks of motorcycle enthusiasts. / So much so, in fact, that when British industrialist Tony Vandervel built his team of Vanwall Grand Prix racing cars, he used the Norton engine as power. Not a Norton engine exactly; Vandervel used four of them. After a series of tests on a watercooled version of the Norton Manx engine (which would, as it turned out, deliver a bit more power than the aircooled original), a four-cylinder engine was built with valves, valve gear, cam timing, pistons and porting from the Norton. It was, as one might imagine, a tremendous success. The car was afflicted with a variety of ailments and it was some time before it won any important races, but Vandervel's bundle-of-Nortons engine was outstanding for its power and reliability.

The servicing of racing machines can present some problems — especially when special tools are required. The Norton does not present this kind of problem. Procedures for dismantling and assembly are uncomplicated, and a minimum of tools of any kind are needed for even the most extensive repair work. Neither is there any need for special tuning or hand-finishing of the engine after purchase. Each of these engines is hand-built at the factory and checked on a dynamometer for output — and then stripped down, inspected for flaws, and reassembled before being sent out to the buyer.

Engine tuners who specialize in re-working the Manx engine can get a bit more than is delivered as stock. In England there are men like the famous Francis Beart, who (with the help of the Norton factory) turns out engines for the continental aces that are substantially more powerful than those being sold over the counter. However, these engines usually have too narrow a power band to be as versatile as those direct from Norton. Some people here in America have also developed a fine touch with the Manx, but their work is mostly confined to getting the engine to deliver, consistently, what it did when it was run on the factory's dynamometer. This information is, incidentally, available to any owner: all he has to do is send the engine's serial number to the factory and he will get a duplicate of the dynamometer card for his particular engine. And, of course, this card is supplied with each new Norton Manx.

The Manx is available as either a 500 or a 350, and you pay your money and take your choice: there is no difference in the price. Indeed, there is very little difference in the machines themselves. The engines are virtually identical, except for carburetor size and bore/stroke dimensions, and the gear ratios are much different, but the cases and the rest of the bike are the same. Obviously, this makes the "smaller" Norton a trifle large for a 350, but it is not too large to win races, and we do not recall hearing any complaints.

Whether 500 or 350, the Norton engine is set into the best frame that can be bought today. It is, of course, the famous Norton "Featherbed" frame, which was introduced in 1950, and which is at least as important to Norton's success as the Manx engine. Basically, it consists of a pair of tubes, which lead down from the steering head, loop under the engine, (one tube on each side of the sump), swing back up behind the transmission and then lead around forward again, terminating at the steering head. In the twelve years since it first appeared, a lot of sheet-metal gusseting has been added, and the tubes have been pinched in slightly at the rear of the fuel tank to allow the rider to get his knees in closer, but it is otherwise unchanged. The true measure of the excellence of the design is the number of other racing bikes that have been built in imitation — they are legion.

At the front of this frame are Norton's "Roadholder" forks, which have also been widely imitated (but not necessarily equalled). These are of the telescopic variety, and have long coil springs inside, and built-in hydraulic damping. As a design, they show nothing particularly remarkable, except that they are unusually sturdy and rigid. Their strength does not appear to carry with it any penalty in weight, for there is evidence of the designer's having given a lot of thought to lightness, too. In action, they are quite soft — especially if one considers that they are made for racing — but the softness of the springs is matched by very heavy damping action, which makes them feel very solid without any harshness.

The same thing is evident in the rear suspension. The swing arm is very rigid, and pivots on wide-base mountings, and the Girling spring/damper units (which are adjustable) give soft springing, with heavy damping. This is, of course, right in line with the best modern practice for both motorcycles and cars, and in the Norton it produces a level of roadholding that ranks second to none.

In road racing, brakes are at least as important as cornering qualities and sheer speed, and the Norton Manx is well endowed in that respect too. The front brake consists of two drums, mounted back-to-back, and no less than four separate brake shoes. These are all mounted to "lead" and they give a fairly strong self-servo action that makes the operating pressure very light. The backingplate sides of the units are facing outward (as they must) and there are air inlets and outlets, with appropriately aimed "scoops" on each side of the wheel. The rear brake is less elaborate, having only (only?) two shoes, one leading and one trailing.

The wheels on the Manx are made of light alloy, and have wire rims, with a prominent reinforcing rib extending inward from each side of the rim. They are light, and strong, and are just one more small item that goes to make the Norton a big success.

The rider of a Manx Norton is given a very comfortable (relative to other racing bikes) perch. The saddle is rather wide, and well padded, and the foot pegs are set far enough back to prevent the cramping of one's legs. The handlebars, which clip on to the forks, are very low, and although this at first feels awkward, it allows a nice crouch and soon begins to feel very natural. Surprisingly, all of the controls are quite soft in their action; the clutch disengages with only the lightest of pressures, and the brakes will do their utmost for an equally gentle touch. The five-gallon tank has knee-notches, and is strapped down by a steel band (with a quick-release clip) that is padded and which serves as a chin rest when the rider is really trying to get down out of the wind.

Our test machines were quite badly set up for our purposes. They had very tall gearing, and there was not really room for them to get going — even on the fairly long Riverside Raceway straight. The 350 was geared reasonably well, but the 500 was pulling Isle of Man gears, which would allow it about 150 mph down the mountain at that famous course, but which was a lot less than ideal here. Actually, Norton can supply a wide range of gearing and sprockets for the Manx, and every machine is delivered with a chart showing all of the gearing option, with road speed and engine speed.

Bad gearing or not, we had a real time with the Nortons. There is a lot of power on tap — ifyou can just keep it turned on. The engine pulls strongly up to about 3500 rpm, and then it just falls dead, with nothing more until it gets up past 4500 rpm. The trick is to slip the clutch enough to keep the engine speed above that critical point until the bike gains enough speed to let in the clutch all the way. It is a technique that takes some practice to acquire, and we let John McLaughlin and Ron Grant do the honors for our acceleration trials. For readers who may not know, John McLaughlin is the number one AFM road racer on a Manx and proprietor of McLaughlin Mtrs. in Duarte, California; Ron Grant is an Englishman now living in this country and a member of McLaughlin's staff; he competes in AFM races on a Manx Norton. The results were not bad: John and Ron got everything that could be had, but the bikes simply would not pull very strongly away from the mark. After they finally began to roll, they went very fast, but that slow starting certainly killed their elapsed times. Given stúmp-yanker gearing, they would show the drag strip boys a thing or two, though, as can be seen from the speed they attained in the quarter. However, standing start acceleration is not the kind of work for which these bikes are intended; it is road racing, and at that they have few equals.

We hate to admit it, but the road holding of the Manx is so good that we cannot really pass judgment on the machine. Experienced riders tell us it is absolutely tops though, and we believe it. The Manx is certainly the best that we have ever tried. The GP Bultaco was pretty terrific, but it was too small and light to have the rock-steady feel of the Manx. One just sits up there on the Norton saddle and works away; none of the small shiftings of weight and fidgetings that seems to be inevitable when we ride had the slightest effect on the bike. It was as stable,

at any speed, as anything we have ever been on —and that includes all of the big and heavy touring bikes.

After getting past the initial period of strangeness with the Norton Manx, we tried to press on a bit and found that (a) our previous experience was not extensive enough to allow us to go really fast and (b) that our courage was not large enough to let us go really fast. Riverside Raceway has several bends that can be taken at over 100 mph on the Manx, and we never did manage all of these at that speed. Screwing up our courage, we would ear-hole one bend in reasonably good style, and find ourselves still marveling that we had made it when we arrived at the next one — which would be, as a consequence, taken in a most untidy fashion. One of our intrepid testers reports that once, when heeled over at what he thought was a fairly conservative angle (it felt very stable and conservative) he caught sight of something not far from the side of his head. A quick glance told him what it was: his shadow.

All in all, the Norton Manx is a machine that beggars description. It goes very fast, and it handles like nothing the average street or dirt rider has even imagined could exist. It is, beyond any doubt, one of the best. The specially constructed, factory sponsored racing machines can and have beaten it, but these bikes are not available to the individual rider — and the Manx is. Each year, to fill advance orders, the Norton factory turns out a batch of their racing machines — approximately 100 examples, both 350s and 500s. The price is not bargain basement, obviously, but it is not really all that high, either, and one thing is certain: the rider who buys a Norton Manx will have a machine that, in this country, is beaten very infrequently. Anyone who is serious about going road racing in GP fashion should give the Manx a lot of thought. •

NORTON

MANX, 500 & 350

SPECIFICATIONS

$1895

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

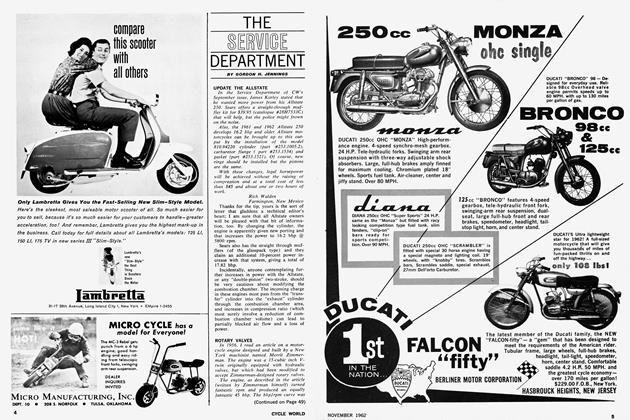

The Service Department

November 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

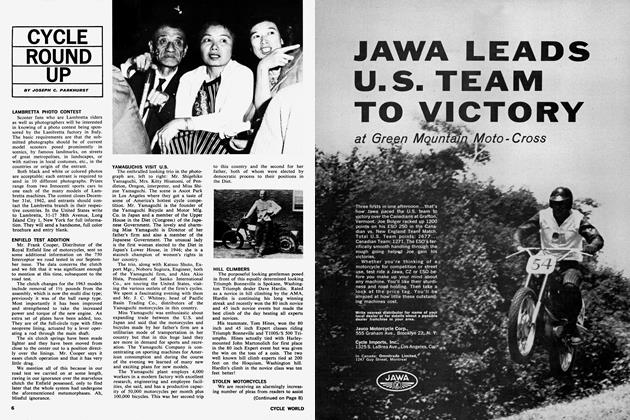

Cycle Round Up

November 1962 By Joseph C. Parkhurst -

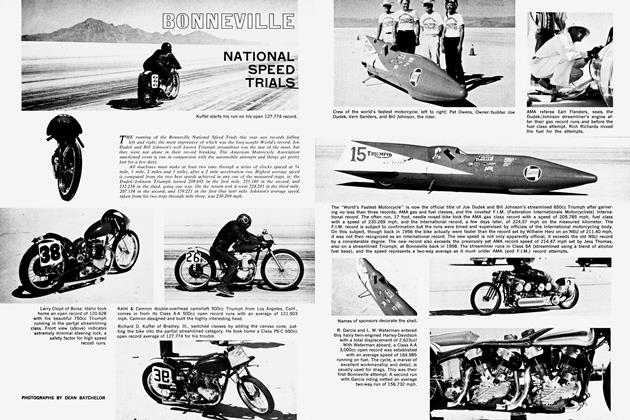

Bonneville

November 1962 -

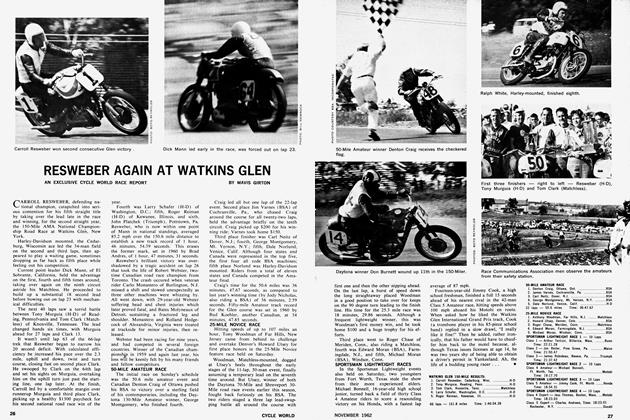

Resweber Again At Watkins Glen

November 1962 By Mavis Girton -

An Exclusive Cycle World Race Report

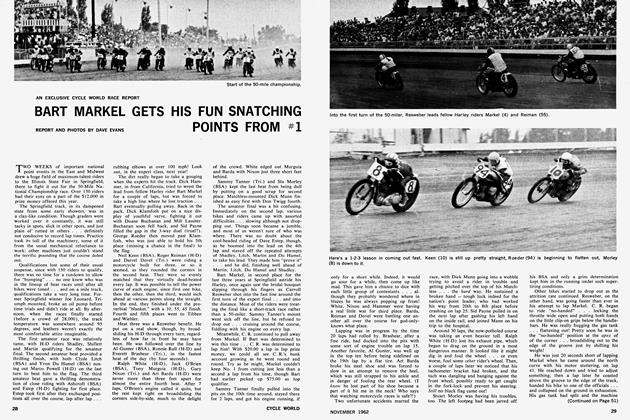

An Exclusive Cycle World Race ReportBart Markel Gets His Fun Snatching Points From #1

November 1962 By Dave Evans -

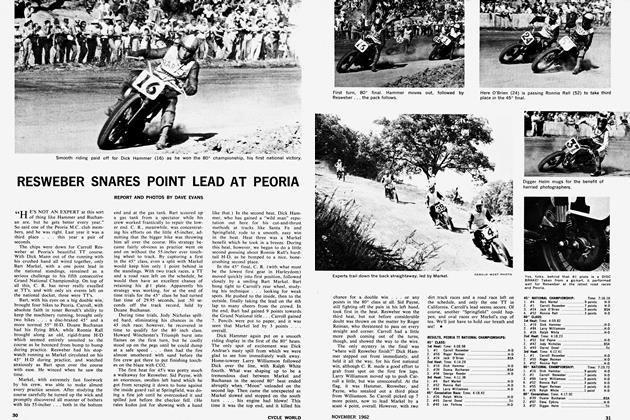

Resweber Snares Point Lead At Peoria

November 1962 By Dave Evans